This morning, my “office” is a nearby Panera, a restaurant known for its Asiago bagels, Light Roast coffee, loud-talking fellow diners, and truly awful piped-in music.

The bagels require toasting twice (sometimes, they actually do that, too), the Light Roast requires that someone makes sure the urn is filled (sometimes, they actually do that, too), and the music/loud-talking fellow diners require I bring my earbuds or headphones (always, I actually always do that, too).

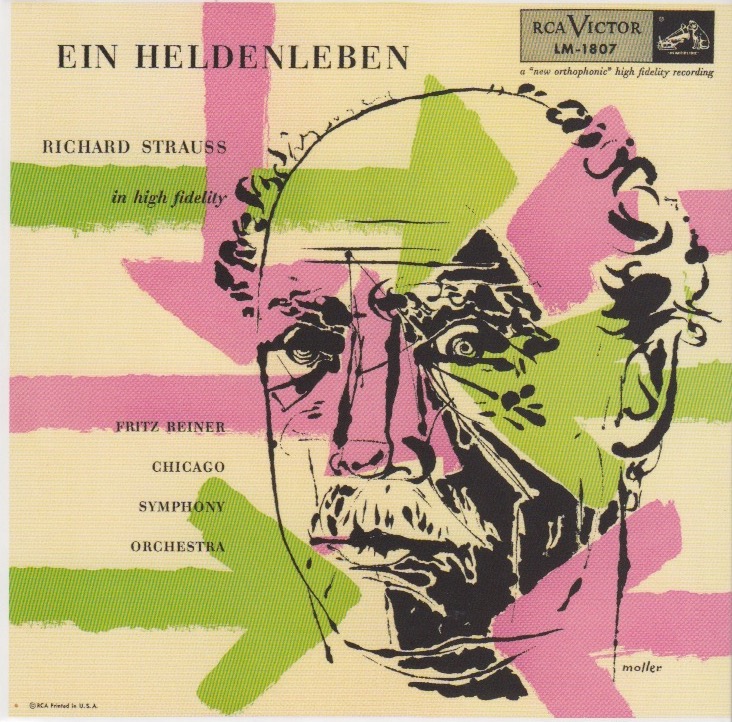

Today’s listening fare is Richard Strauss’ Ein Heldenleben (“A Hero’s Life”). It is, like Also sprach Zarathustra from Day 1, a “tone poem,” which is a phrase I’d never encountered before in my musical adventures, which – to be fair – is likely because my musical adventures were of music that was composed before the advent of the tone poem.

From it’s entry on Wikipeida,

Ein Heldenleben (A Hero’s Life), Op. 40, is a tone poem by Richard Strauss. The work was completed in 1898. It was his eighth work in the genre, and exceeded any of its predecessors in its orchestral demands. Generally agreed to be autobiographical in nature despite contradictory statements on the matter by the composer, the work contains more than thirty quotations from Strauss’s earlier works, including Also sprach Zarathustra, Till Eulenspiegel, Don Quixote, Don Juan, and Death and Transfiguration.

Okay. What’s a “tone poem”?

Again, I turn to an entry on Wikipedia for the answer, and discover,

A symphonic poem or tone poem is a piece of orchestral music, usually in a single continuous movement, which illustrates or evokes the content of a poem, short story, novel, painting, landscape, or other (non-musical) source. The German term Tondichtung (tone poem) appears to have been first used by the composer Carl Loewe in 1828. The Hungarian composer Franz Liszt first applied the term Symphonische Dichtung to his 13 works in this vein.

While many symphonic poems may compare in size and scale to symphonic movements (or even reach the length of an entire symphony), they are unlike traditional classical symphonic movements, in that their music is intended to inspire listeners to imagine or consider scenes, images, specific ideas or moods, and not (necessarily) to focus on following traditional patterns of musical form such as sonata form. This intention to inspire listeners was a direct consequence of Romanticism, which encouraged literary, pictorial and dramatic associations in music.

I let that slide in yesterday’s post. In fact, I didn’t really give it much thought. I read “tone poem” in the Wiki description of Also sprach Zarathustra but I just took it to mean a description of that particular piece of music, not a designation of a genre or type of musical composition. My bad.

Wouldn’t a modern-day equivalent of a tone poem be a movie soundtrack?

Okay, let’s get down to the brass tacks.

The Objective Stuff

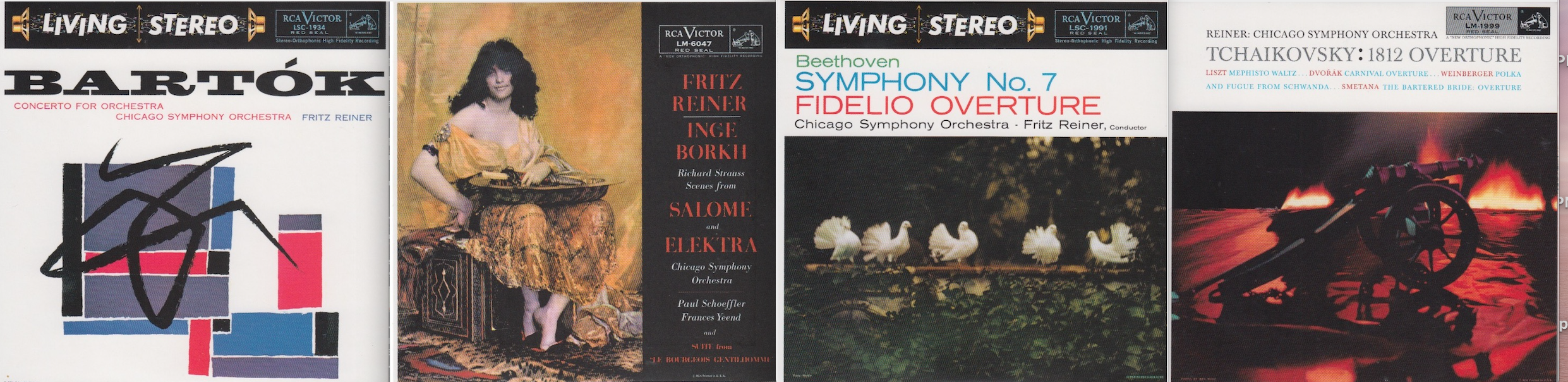

Ein Heldenleben was complete in 1898. Richard Strauss (1864-1949) was 34. Fritz Reiner (1888-1963) was 66 when he conducted it in 1954. It was performed in Orchestra Hall in Chicago on March 6, 1954. When this album was originally released, it featured these two notices on the back cover:

- “New Orthophonic” High Fidelity Recording

- Beware the Blunted Needle!

Good to know.

The “blunted needle” part I can understand. I remember what that was like. But what is a “New Orthophonic” High Fidelity Recording? According to a thread on the Discogs web site,

New Orthophonic is when they switched from purely acoustic to electric sound recording techniques. Guaranteed High Fidelity is a marketing tool used to say this is the best sounding whatever currently available to buy.

The Subjective Stuff

Recording quality: 5

Overall musicianship: 5

CD booklet notes: 4

CD “album cover” information: 3.5

How does this make me feel: 4.5

The hardcover booklet that came with the box set included information I wanted: The name of the violinist who played so sublimely: John Weicher, who I believe lived from 1904-1969. And now I see that John Weicher played violin on the previous album, Also sprach Zarathustra. He was really good.

Why does Ein Heldenleben rate more highly than Also sprach Zarathustra. I don’t know. But I found the music to be more engaging, more melodic. More emotive. Plus, there was John Weicher’s violin solo. When a musician stands out in one of these already marvelous recordings, I sit up and take notice.

The more I listened to this recording, the more it grew on me. After hearing it 4-5 times, I’d say it was a remarkable composition. I’d listen to this again.