Today is the last day of my latest musical journey!

To my ears, a little Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) goes a long way.

Whereas Haydn seems very staid and “by the book” to me, Bach seems busy, percussive, and, like a very rich chocolate, capable of giving me a stomach ache if I ingest too much.

I think it’s the harpsichord that does it. A little harpsichord is marvelous. It immediately alerts the listener that he’s about to hear music from the Baroque period. Whenever TV shows (particularly in the 1960s) wished to convey an old-timey mood, they’d enlist someone to play a harpsichord and – voila! – an old-timey mood would be conveyed.

Example: the episode (Season 3, Episode 27) “Barney’s First Car” from The Andy Griffith Show.

Deputy Fife buys a car from an old lady (played by Ellen Corby), that turns out to be a lemon. As Andy and Barney later discover, Myrt “Hubcaps” Lesh and her gang are in business peddling defective (perhaps even stolen) automobiles. Whenever Mrs. Lesh appeared on screen, the harpsichord would accompany her, thereby setting the mood that she’s an old lady from a bygone era.

So harpsichord can do wondrous things.

But, too much harpsichord gives me a headache. I don’t know why. Possibly because when it’s playing I can think of nothing other than, “This is a harpsichord. People don’t play these much anymore. Thank God for that. This is a harpsichord, from the Baroque period. I do so wish it would stop playing. This is a harpsichord.”

So even though today’s concerto by Bach is scored for harpsichord, it’s played on piano (a much softer-sounding instrument, more emotionally expressive instrument) by Andre Tchaikovsky (1935-1982), whom I encountered on Day 40 as he performed Mozart Concerto No. 25.

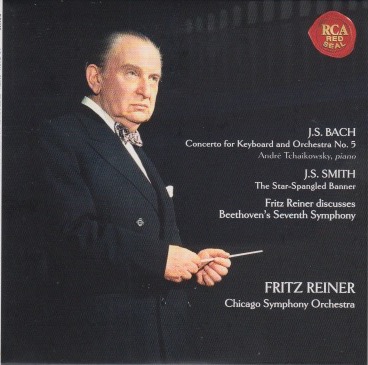

Inserted in between Bach’s Concerto for Keyboard and Orchestra and the beginning of Movement III (Allegro con brio) from Beethoven’s Seventh, which Ludwig himself remarked was one of his best works, are two interesting choices for an album:

A. The Star Spangled Banner by John Stafford Smith (1750-1836), and

B. Fritz Reiner, himself, talking about Beethoven’s Seventh and the challenges it poses

I’m not sure why either one of those are there. But I’m glad they are.

“The Star Spangled Banner” was written as “The Anacreontic Song” and it was likely composed in 1773 for the Anacreontic Society.

This is a fascinating bit of lore (of which I was unaware), so I hope you take the time to read about the song and the society.

First, the song (from its entry on Wikipedia):

“The Anacreontic Song“, also known by its incipit “To Anacreon in Heaven“, was the official song of the Anacreontic Society, an 18th-century gentlemen’s club of amateur musicians in London. Composed by John Stafford Smith, the tune was later used by several writers as a setting for their patriotic lyrics. These included two songs by Francis Scott Key, most famously his poem “Defence of Fort McHenry”. The combination of Key’s poem and Smith’s composition became known as “The Star-Spangled Banner”, which was adopted as the national anthem of the United States of America in 1931.

The Anacreontic Society was a gentlemen’s club of the kind that was popular in London in the late eighteenth century. In existence from approximately 1766 to 1792, the Society was dedicated to the ancient Greek poet Anacreon, who was renowned for his drinking songs and odes to love. Its members, who consisted mainly of wealthy men of high social rank, would meet on Wednesday evenings to combine musical appreciation with eating and drinking.

The Society met twelve times a year. Each meeting began at half past seven with a lengthy concert, featuring “the best performers in London”, who were made honorary members of the Society.[1]

The Society came to an end after the Duchess of Devonshire attended one of its meetings. Because “some of the comic songs [were not] exactly calculated for the entertainment of ladies, the singers were restrained; which displeasing many of the members, they resigned one after another; and a general meeting being called, the society was dissolved”. It is not clear exactly when this incident occurred, but in October 1792 it was reported that “The Anacreontic Society meets no more; it has long been struggling with symptoms of internal decay”.

Then, the society (from its entry on Wikipedia):

The Anacreontic Society was a popular gentlemen’s club of amateur musicians in London founded in the mid-18th century. These barristers, doctors, and other professional men named their club after the Greek court poet Anacreon, who lived in the 6th century B.C. and whose poems, “anacreontics”, were used to entertain patrons in Teos and Athens. Dubbed “the convivial bard of Greece”, Anacreon’s songs often celebrated women, wine, and entertaining.

While the society’s membership, one observer noted, was dedicated to “wit, harmony, and the god of wine”, their primary goal (beyond companionship and talk) was to promote an interest in music. The society presented regular concerts of music, and included among their guests such important musicians as Joseph Haydn, who was the special guest at their concert in January 1791.

There is also evidence of an Anacreontic Society having existed at St Andrews University in the late 18th century in much the same vein as the Anacreontic Society of London. However, due to the club’s informal nature, detailed accounts of the group are sparse. The collection of the Irish Anacreontic Society, active in Dublin from 1740 to 1865, is among the special collections of the Royal Irish Academy of Music.

According to an anonymous “History of the Anacreontic Society” published in 1780, the Society was founded “about the year 1766” by one Jack Smith. The Society initially met in various taverns, and then moved to the London Coffee House on Ludgate Hill. It subsequently relocated to the Crown and Anchor tavern in The Strand in order to accommodate an expansion in its membership from 25 to 40. Its membership later increased to 80.

A musical high-point of the society occurred in January 1791, when Haydn attended a meeting at which the twelve-year-old Johann Hummel performed, “astonish[ing] the company with a most admirable performance of a favourite English ballet, with variations, on the harpsichord”.

The first two compositions were recorded at Orchestra Hall, Chicago. Bach’s Concerto was recorded on February 15, 1958. Smith’s “Star Spangled Banner” was recorded on November 9, 1957. I have no idea when Beethoven’s Seventh was recorded. The book that comes with the box set doesn’t mention it’s recording date.

The Subjective Stuff

Recording quality: 5 (all)

Overall musicianship: 5 (all)

CD booklet notes: 2

CD “album cover” information: 2 (just the basics)

How does this make me feel: 5

This was a tremendous way to end my exploration through the Fritz Reiner Chicago Symphony Orchestra The Complete RCA Album Collection box set! The music was engaging, it was a very nice touch to hear Maestro Reiner’s voice. And I learned about The Anacreontic Society.

I’d definitely listen to this album again. It’s basically just a collection of snippets. But they were all quite fun to hear compiled together.

Because people always ask me, after I complete one of my projects, something like, “Which album did you like best?” or “Which performer did you like best?” or even “Would you buy this box set knowing then what you do now?”

The answer’s are obvious if you’ve been reading along. I prefer the composers from the Classical period (Beethoven, especially). I am most fond of pianists such as Byron Janis and Arthur Rubinstein. And I enjoyed discovering composes I had not heard before, such as Alan Hovhaness or Antonin Dvorak or Franz Schubert.

Would I pay what I paid for this box set again? No. I bought it out of print, rare, and expensive.

Did I enjoy myself? Yes. It was nice to return to a musical project like this.

If you can find one of these box sets at a price below, say, $300, I’d recommend buying it. It’s a very solid education in music played by world-renowned experts.