I admit it: I don’t get Bartok.

Oh, I can read who he was and what he accomplished. And I, like many others, am impressed by his credentials. In fact, to be honest, I just learned from his entry on Wikipedia things about him that I didn’t know:

Béla Viktor János Bartók; 25 March 1881 – 26 September 1945) was a Hungarian composer, pianist, and ethnomusicologist. He is considered one of the most important composers of the 20th century; he and Franz Liszt are regarded as Hungary’s greatest composers. Through his collection and analytical study of folk music, he was one of the founders of comparative musicology, which later became ethnomusicology.

In 1909, at the age of 28, Bartók married Márta Ziegler (1893–1967), aged 16. Their son, Béla Bartók III, was born the next year. After nearly 15 years together, Bartók divorced Márta in June 1923. Two months after his divorce, he married Ditta Pásztory (1903–1982), a piano student, ten days after proposing to her. She was aged 19, he 42. Their son, Péter, was born in 1924.

Raised as a Catholic, by his early adulthood Bartók had become an atheist. He later became attracted to Unitarianism and publicly converted to the Unitarian faith in 1916. Although Bartók was not conventionally religious, according to his son Béla Bartók III, “he was a nature lover: he always mentioned the miraculous order of nature with great reverence.” As an adult, Béla III later became lay president of the Hungarian Unitarian Church.

In 1911, Bartók wrote what was to be his only opera, Bluebeard’s Castle, dedicated to Márta. He entered it for a prize by the Hungarian Fine Arts Commission, but they rejected his work as not fit for the stage.

After his disappointment over the Fine Arts Commission competition, Bartók wrote little for two or three years, preferring to concentrate on collecting and arranging folk music. He found the phonograph an essential tool for collecting folk music for its accuracy, objectivity, and manipulability. He collected first in the Carpathian Basin (then the Kingdom of Hungary), where he notated Hungarian, Slovak, Romanian, and Bulgarian folk music.

Although he became an American citizen in 1945, shortly before his death, Bartók never felt fully at home in the United States. He initially found it difficult to compose. Although he was well known in America as a pianist, ethnomusicologist and teacher, he was not well known as a composer. There was little American interest in his music during his final years. He and his wife Ditta gave some concerts, although demand for them was low. Bartók, who had made some recordings in Hungary, also recorded for Columbia Records after he came to the US; many of these recordings (some with Bartók’s own spoken introductions) were later issued on LP and CD.

As his body slowly failed, Bartók found more creative energy, and he produced a final set of masterpieces, partly thanks to the violinist Joseph Szigeti and the conductor Fritz Reiner (Reiner had been Bartók’s friend and champion since his days as Bartók’s student at the Royal Academy). Bartók’s last work might well have been the String Quartet No. 6 but for Serge Koussevitzky’s commission for the Concerto for Orchestra. Koussevitsky’s Boston Symphony Orchestra premièred the work in December 1944 to highly positive reviews. The Concerto for Orchestra quickly became Bartók’s most popular work, although he did not live to see its full impact.

See? There are many things in those paragraphs, alone, that intrigue me. The first: Ethnomusicology. What is it?

From its entry on Wikipedia,

Ethnomusicology is the study of music from the cultural and social aspects of the people who make it. It encompasses distinct theoretical and methodical approaches that emphasize cultural, social, material, cognitive, biological, and other dimensions or contexts of musical behavior, in addition to the sound component.

Folklorists, who began preserving and studying folklore music in Europe and the US in the 19th century, are considered the precursors of the field prior to the Second World War. The term ethnomusicology is said to have been coined by Jaap Kunst from the Greek words ἔθνος (ethnos, “nation”) and μουσική (mousike, “music”), It is often defined as the anthropology or ethnography of music, or as musical anthropology.

As Spock would say, “Fascinating.”

Second, Bartok’s conversion from Catholicism to atheism to Unitarianism. The first two, I understand. The third, I can guess at from my studies of comparative religions. But, let’s take a peek on Wikipedia to make sure:

Unitarianism (from Latin unitas “unity, oneness”, from unus “one”) is a Christian theological movement that believes that the God in Christianity is one entity, as opposed to a Trinity (tri- from Latin tres “three”). Most other branches of Christianity define God as one being in three persons: the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Unitarian Christians, therefore, believe that Jesus was inspired by God in his moral teachings, and he is a savior, but he was not a deity or God incarnate.

Unitarianism is also known for the rejection of several other Western Christian doctrines, including the doctrines of original sin, predestination, and the infallibility of the Bible. In J. Gordon Melton’s Encyclopedia of American Religions, the Unitarian tradition is classified among “the ‘liberal’ family of churches”. Unitarians place emphasis on the ultimate role of reason in interpreting scriptures, and thus freedom of conscience and freedom of the pulpit are core values in the tradition.

Yeah. That’s about what I thought.

Frankly, I’ve never been able to understand the liberal ideology. At some point, I have to wonder, “Why bother with it at all?” I understand the pull toward rejecting a lot of doctrines that don’t seem to make sense. Or shying away from atheism because it, too, doesn’t make sense. (Especially for one such as Bartok who saw so much order and beauty in nature.) But it’s another thing to reject fundamental doctrines that have been around for a millennia or two. Seems incredibly audacious to me. I mean, isn’t that, basically, just creating my own religion?

The hell do I know? I’m no composer, ethnomusicologist, folklorist, Catholic, atheist, or Unitarian. My accomplishments in life are measured by whether or not I can get out of bed by 5:30 every morning so that I can get to work.

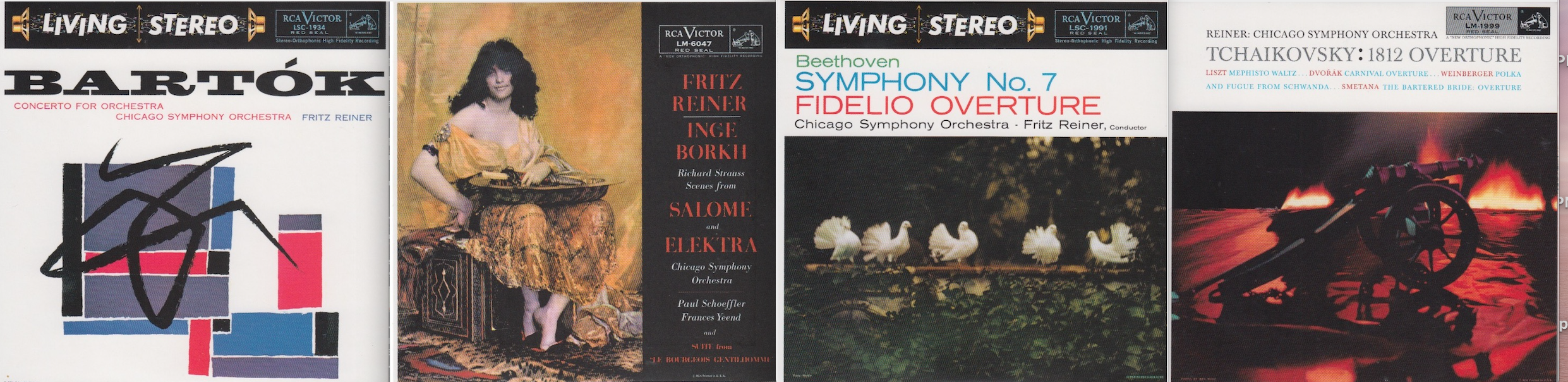

The third thing that jumped out at me is that Bartok and Reiner were friends. There’s a picture of the two of them in the Fritz Reiner Chicago Symphony Orchestra book that came with the box set. (It’s on page 57 if you care to look.)

The fourth thing that I wanted to explore, and I would have anyway because that’s what these projects are all about, is Bartok’s Concerto For Orchestra. From its entry on Wikipeida:

The Concerto for Orchestra, Sz. 116, BB 123, is a five-movement orchestral work composed by Béla Bartók in 1943. It is one of his best-known, most popular, and most accessible works.

The score is inscribed “15 August – 8 October 1943”. It was premiered on December 1, 1944, in Symphony Hall, Boston, by the Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Serge Koussevitzky. It was a great success and has been regularly performed since.

It is perhaps the best-known of a number of pieces that have the apparently contradictory title Concerto for Orchestra. This is in contrast to the conventional concerto form, which features a solo instrument with orchestral accompaniment. Bartók said that he called the piece a concerto rather than a symphony because of the way each section of instruments is treated in a soloistic and virtuosic way.

Again, fascinating.

Oh, I have to add a fifth thing of interest: The letters “Sz.” To what do they refer? Again, I turn to Wiki:

András Szőllősy; 27 February 1921 in Orăştie – 6 December 2007 in Budapest) was the creator of the Szőllősy index (abbreviated “Sz.”), a frequently used index of the works of Hungarian composer Béla Bartók.

Now I know.

No, wait. I must ad a sixth item of interest: The name Serge Koussevitzky, which has come up a few times in my reading. Who was he? Again, Wiki to the rescue:

Serge Alexandrovich Koussevitzky; 1874 – 1951) was a Russian-born conductor, composer and double-bassist, known for his long tenure as music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra from 1924 to 1949.

Okay. Enough with the background.

What do I think of the music itself?

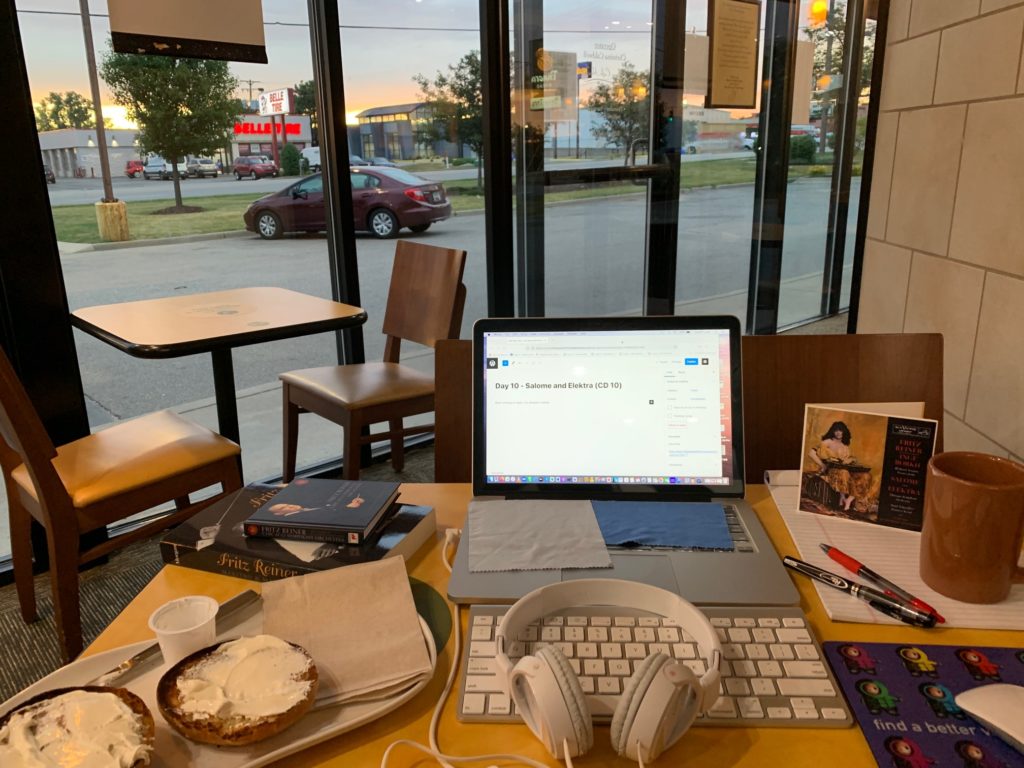

I wrote at the outset (in between bites of an Asiago bagel – toasted twice, mind you! – and sips of Light Roast coffee – that I don’t get Bartok.

What I mean by that is his music never really clicked with me. I always found it to be busy (or overly expressive), unmelodic, somber, and more like a Broadway musical than a symphony. In fact, the fifth movement (Finale – Presto) of this particular piece sounds like something I’d hear from Leonard Bernstein in one of his musicals.

The Objective Stuff

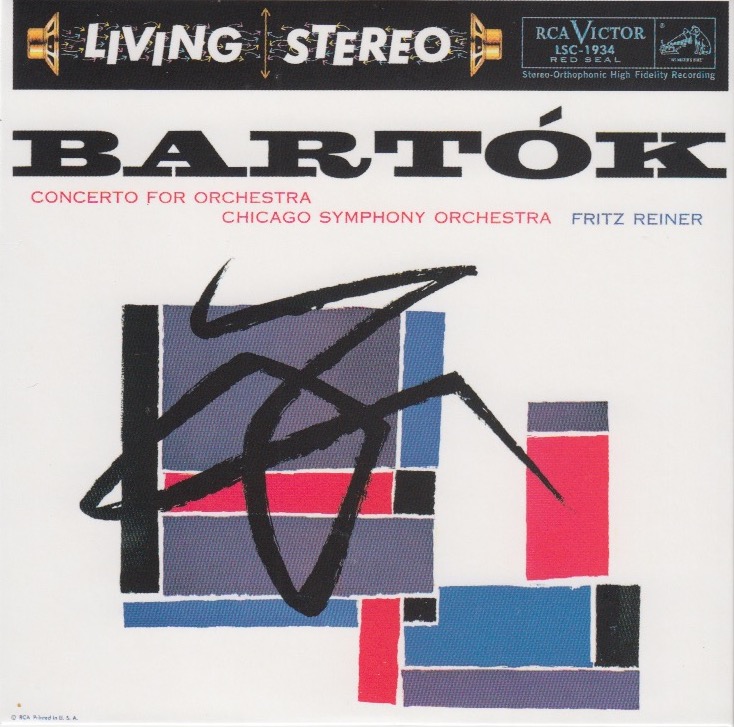

Bartok composed this when he was 62. Fritz Reiner was 67 when he conducted it. It was recorded in Orchestra Hall by RCA Victor in Living Stereo, which makes a huge difference in sound quality.

The Subjective Stuff

Recording quality: 5

Overall musicianship: 5

CD booklet notes: 3.5

CD “album cover” information: 5

How does this make me feel: 4

I’ve listened to Concerto For Orchestra some 4-5 times so far and I’ve developed an appreciation for parts of it. Some of it is very evocative. Some is wildly entertaining. To me, it still sounds like the music composed for a fight scene in a stage play. (Think: West Side Story.) And I’m not sure it all hangs together for me. But…

I know what it is!

Bartok is challenging listening. It’s not melodic and deeply emotional like Beethoven’s music, or Bruckner’s. It’s not clever and lively like Mozart’s. No. This is more like Progressive Rock in that it requires active listening. And I do mean active. I have to study each movement, each passage, to find something I can enjoy.

What Bartok’s music lacks in hummable melodies, it more than makes up for in…what? Density? Depth? Vastness? I don’t know. Can’t put my finger on the proper word.

All I know is that I don’t hate this – at least, not after five listens. Bartok’s music has to grow on me.

Sort of like fungus on a tree.