Now this is more like it.

As I’ve mentioned, several years ago (July 21, 2018 – December 29, 2018, to be precise) I spent 162 Days with Beethoven “Evaluating Symphonies 1-9 from 18 CD Box Sets.” (Famed conductor Herbert von Karajan was in there twice, with two different box sets. If memory serves, he recorded four Beethoven symphonies cycles. Two are considered legendary – 1963 and 1977. So I bought both.)

I developed a very love of Beethoven’s music. In fact, out of all of the great composers, I discovered that Beethoven was my favorite. Out of all of them. Followed by Anton Bruckner. And then Mozart. I tell people, “Beethoven touches me emotionally. Bruckner touches me spiritually. And Mozart touches me intellectually.”

I realize there are different strokes for different folks, and creativity comes in all stripes.

But give me Beethoven, Bruckner, and Mozart any day over Strauss, Bartok, and Tchaikovsky. Any day. (And when I want to be completely bored out of my mind, I listen to Bach or Haydn, both of which were brilliant from a technical standpoint, but couldn’t write an emotionally moving passage of music if their lives depended on it.)

To give you an example of how deeply Beethoven affects me, when I listen to Movement II (Allegretto), I weep. I kid you not. This piece of music is so undeniably profound and emotionally impactful, so perfectly constructed, that I cannot believe it was composed by a human being. The first time I heard Symphony No. 7, Movement II, I was so moved that I made my wife listen to it later that night. Seriously. I hauled out the CD and popped it into our player in the living room. I dimmed the lights, and said, “Listen to this.” I pushed play. And I remember choking up, again. She, however, was nonplussed. Different strokes, eh?

In my notes (November 12, 2018) regarding Wilhelm Furtwangler’s interpretation of this symphony, I wrote:

The first time I heard this performance, I was underwhelmed. In fact, I thought, “This is going to be a sleepy performance, isn’t it?”

But then, after about four listens through its entirety, during the middle of the beloved Movement II, it clicked.

I was deeply moved, carried away by the heartbreaking nature of the second movement.

And then everything else opened up.

The power of that second movement cannot be overstated. It is everything to me, the fulcrum upon which the entire symphony balances.

Furtwangler knocked it out of the park with this movement and, thus, saved the entire performance.

This is a spirited, muscular performance of Beethoven’s Seventh. The recording isn’t too bad, despite it being recorded 68 years ago. I’ve heard worse. I’ve heard better. It’s not bad.

What I discovered listening to it in three different places this morning is that it requires repeated listening to crack it open, to make a competent decision. Once its secrets are revealed, it becomes a very powerful performance, indeed.

I can wholeheartedly recommend Maestro Furtwangler’s performance.

“Huzzah!”

And there you have it.

That’s what this second movement means to me.

Aside from Beethoven’s gorgeous and gut-wrenching Moonlight Sonata, I can think of no more heartbreaking music than Movement II from Symphony No. 7, which was composed between 1811-1812. Beethoven was 41 or 42, and – according to its entry on Wikipedia,

Beethoven’s life at this time was marked by a worsening hearing loss, which made “conversation notebooks” necessary from 1819 on, with the help of which Beethoven communicated in writing

Knowing that makes this symphony even more special to me, and even more heartbreaking.

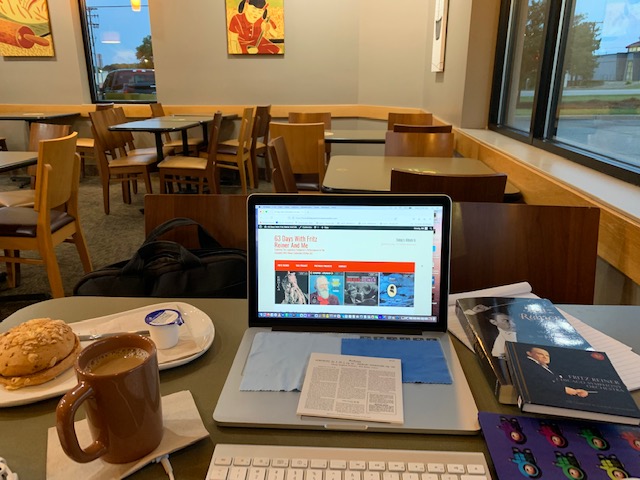

So I am in my element this morning.

The question of the day is, how does Fritz Reiner’s interpretation of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7 in A, Op. 92, stack up against 17 other conductors and their orchestras? Lucky for Fritz, I don’t remember much of what I heard three years ago. I do know, however, that I’ve heard much more impactful performances of Movement II. From Leonard Bernstein, for example.

Maybe it’s Lenny’s flamboyant direction (watch for yourself here) and expressive face that sells his performance of Beethoven’s 7th. But when I listen to and watch this – especially Movement II (where I started this clip below) – I cannot help but feel Beethoven’s emotions, deep and wide and…hurting. Bernstein’s Beethoven has a power that I did not feel in Reiner’s interpretation.

But I’ll get to that later.

The Objective Stuff

In the meantime, a bit about Beethoven’s 7th from its entry on Wikipedia,

The Symphony No. 7 in A major, Op. 92, is a symphony in four movements composed by Ludwig van Beethoven between 1811 and 1812, while improving his health in the Bohemian spa town of Teplice. The work is dedicated to Count Moritz von Fries.

At its premiere, Beethoven was noted as remarking that it was one of his best works. The second movement, Allegretto, was the most popular movement and had to be encored. The instant popularity of the Allegretto resulted in its frequent performance separate from the complete symphony.

A bit about Fidelio Overture, Op. 72b, from its entry on Wikipeida,

Fidelio, originally titled Leonore, oder Der Triumph der ehelichen Liebe (Leonore, or The Triumph of Marital Love), Op. 72, is Ludwig van Beethoven’s only opera. The German libretto was originally prepared by Joseph Sonnleithner from the French of Jean-Nicolas Bouilly, with the work premiering at Vienna’s Theater an der Wien on 20 November 1805. The following year, Stephan von Breuning helped shorten the work from three acts to two. After further work on the libretto by Georg Friedrich Treitschke, a final version was performed at the Kärntnertortheater on 23 May 1814. By convention, both of the first two versions are referred to as Leonore.

The libretto, with some spoken dialogue, tells how Leonore, disguised as a prison guard named “Fidelio”, rescues her husband Florestan from death in a political prison.

These performances (Symphony No. 7 and Fidelio) were recorded on October 24, 1955 (tracks 1-4, which is Symphony No. 7) and on December 12, 1955 (which is track 5 – Fidelio Overture, Op. 72b) at Orchestra Hall. Beethoven was 41 or 42 when he wrote Symphony No. 7. He was 34 when he composed his only opera. Reiner was 67 when he conducted these pieces of music. These performances were released as an RCA Victor Living Stereo album.

The Subjective Stuff

Recording quality: 4.5

Overall musicianship: 4

CD booklet notes: 2.5

CD “album cover” information: 5

How does this make me feel: 5

This is a superb performance and a worthy album to own. In fact, this is my favorite to date of the Fritz Reiner collection. The recording quality is very high, with nice depth and separation between the instruments. There’s a power and passion clearly evident here.

Hearing Beethoven after Strauss and Tchaikovsky and Bartok only deepens my appreciation for Beethoven. This is complex, emotional, uplifting, grand, and life-giving music.

As I alluded earlier, Fritz Reiner and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra do a fine job with this performance of Beethoven’s 7th. It seems incredibly…adequate. But not as powerful as others I’ve heard.

The Fidelio, on the other hand, is a rousing kick in the pants from start to finish. Unbridled exuberance.

I could listen to this CD again. And again. It’s my favorite to date.