I arose this morning, feeling a bit groggy and unsure about plopping my butt in a chair at the local eatery to which I hie myself at 6am most mornings, but then I looked at what today’s musical fare would be (whatever it was would surely beat what the local eatery would be playing over its PA) and discovered that the music du jour was Tchaikovksy’s 1812 Overture.

“That ought to wake me up,” I mused aloud. “I wonder if there will be cannons in Orchestra Hall to accompany Maestro Reiner. Or would he have to school the cannon operators in the proper use of such weapons of warfare? Actually, that would have been funny: a conductor belittling a guy with a cannon. I would have paid to see that High Noon showdown.”

According to its entry on Wikipedia,

The Year 1812 Solemn Overture, Op. 49, popularly known as the 1812 Overture, is a concert overture in E♭ major written in 1880 by Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky to commemorate the successful Russian defense against Napoleon’s invading Grande Armée in 1812.

The overture debuted in Moscow on 20 August 1882, conducted by Ippolit Al’tani under a tent near the then-almost-finished Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, which also memorialized the 1812 defense of Russia. Tchaikovsky himself conducted another performance at the dedication of Carnegie Hall in New York City. This was one of the first times a major European composer visited the United States.

The 15-minute overture is best known for its climactic volley of cannon fire, ringing chimes, and a brass fanfare finale. It has also become a common accompaniment to fireworks displays on the United States’ Independence Day. The 1812 Overture went on to become one of Tchaikovsky’s most popular works, along with his ballet scores to The Nutcracker, The Sleeping Beauty, and Swan Lake.

I often wondered what the story was behind the 1812 Overture. Now I know.

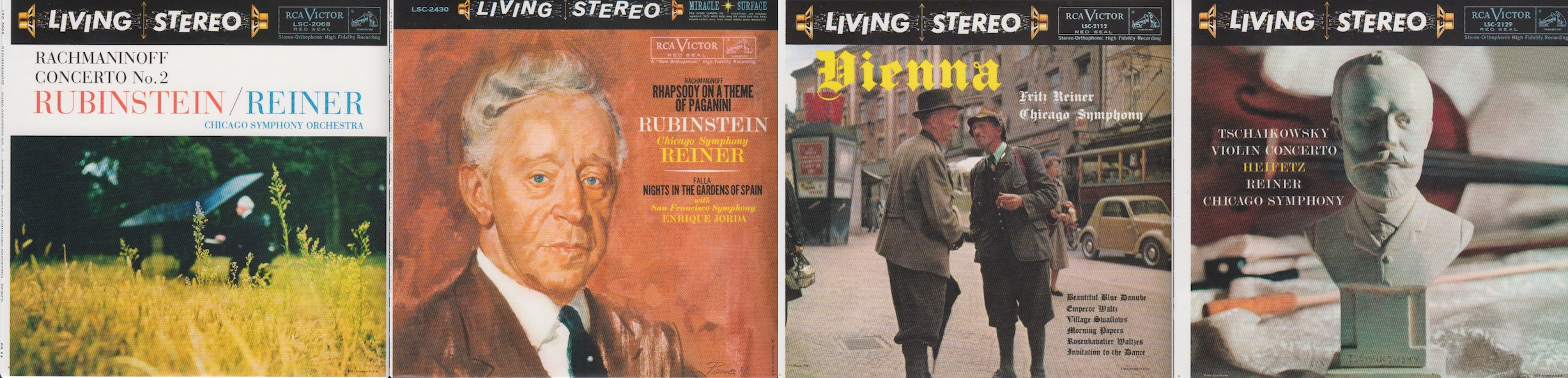

Today’s album features five different composers and five different compositions:

Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) – 1812 Overture

Franz Liszt (1811-1886) – Mephisto Waltz

Jaromír Weinberger (1896-1967) – Polka and Fugue from “Schwanda”

Bedrich Smetana (1824-1884) – “The Bartered Bride” Overture

Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904) – Carnival Overture

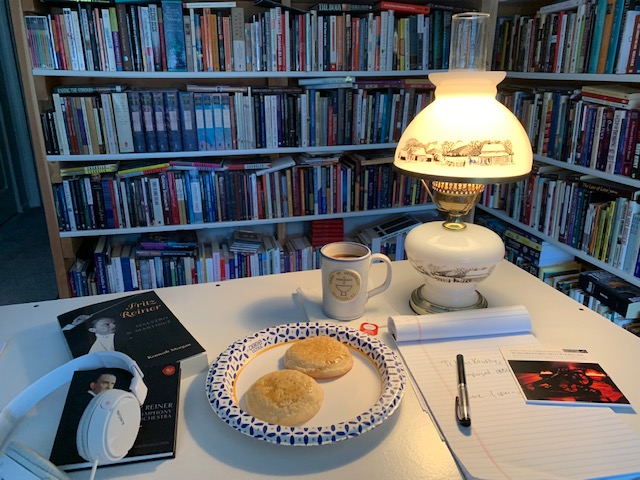

My time at the local eatery with the Asiago bagels (toasted twice!) and Light Roast coffee was cut short. So I found myself back in my home office, a situation that I used to my advantage by brewing up some Twinings English Breakfast tea and toasting a couple of crumpets, which I slathered with butter and honey.

Now, I can listen to these five composers!

I’ve already mentioned Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture. So, I’ll focus on the rest of them now that I’m satiated with crumpets and tea.

If there’s a theme to today’s album it’s nationalism. Or, to put it another way, a pride in one’s nationality and a desire to present to the world music unique to one’s country.

The Objective Stuff

From his entry on Wikipedia,

Franz Liszt (1811-1886) was a Hungarian composer, virtuoso pianist, conductor, music teacher, arranger, and organist of the Romantic era. He was also a writer, philanthropist, Hungarian nationalist, and Franciscan tertiary.

Liszt gained renown in Europe during the early nineteenth century for his prodigious virtuosic skill as a pianist. He was a friend, musical promoter and benefactor to many composers of his time, including Frédéric Chopin, Charles-Valentin Alkan, Richard Wagner, Hector Berlioz, Robert Schumann, Clara Schumann, Camille Saint-Saëns, Edvard Grieg, Ole Bull, Joachim Raff, Mikhail Glinka, and Alexander Borodin.

A prolific composer, Liszt was one of the most prominent representatives of the New German School (German: Neudeutsche Schule). He left behind an extensive and diverse body of work that influenced his forward-looking contemporaries and anticipated 20th-century ideas and trends. Among Liszt’s musical contributions were the symphonic poem, developing thematic transformation as part of his experiments in musical form, and radical innovations in harmony

From its entry on Wikiipedia,

The Mephisto Waltzes (German: Mephisto-Walzer) are four waltzes composed by Franz Liszt from 1859 to 1862, from 1880 to 1881, and in 1883 and 1885. Nos. 1 and 2 were composed for orchestra, and later arranged for piano, piano duet and two pianos, whereas nos. 3 and 4 were written for piano only. Of the four, the first is the most popular and has been frequently performed in concert and recorded.[1]

Associated with the Mephisto Waltzes is the Mephisto Polka, which follows the same program as the other Mephisto works.

So, there is more than one Mephisto Waltz? Interesting.

From his entry on Wikipedia,

Jaromír Weinberger (8 January 1896 – August 8, 1967) was a Bohemian born Jewish subject of the Austrian Empire, who became a naturalized American composer.

Weinberger composed over 100 works, including operas, operettas, choral works, and works for orchestra. Until recently, the only one which remained even on the fringe of the repertoire was opera Schwanda the Bagpiper (Švanda dudák), a worldwide success after its première in 1927. The opera is still performed occasionally, and the Polka and Fugue from it is often heard in a concert version. The artists of the Walt Disney studio considered making it into a segment for Fantasia 2000, but instead chose Shostakovich’s Piano Concerto No. 2 in F major, in the form of Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Steadfast Tin Soldier”. Recent revivals of Frühlingsstürme (2019, Berlin Komische Oper and DVD/Blu-ray) and Wallenstein (2012, Wiener Konzerthaus and CD) indicate a renewed interest in his distinctive work.

Weinberger used a varied musical language. His studies in Prague and Leipzig stressed formal control and contrapuntal mastery; following the example of his teachers, Křička, Novák and Reger, Weinberger’s works exhibit control, but are also playful. This combination received both praise and criticism.

In January 1949, Weinberger moved to St. Petersburg, Florida. In later life, he developed cancer of the brain. This, together with money worries and the neglect of his music, prompted him to take a lethal sedative overdose in August 1967. His wife, Jane Lemberger Weinberger (also known as Hansi), died on July 31, 1968.

Gee whiz. That’s horrible. Makes me want to study the guy in more depth just to honor his creative output. I don’t know. I hate stories like that.

From its entry on Wikipedia,

Schwanda the Bagpiper (Czech: Švanda dudák), written in 1926, is an opera in two acts (five scenes), with music by Jaromír Weinberger to a Czech libretto by Miloš Kareš, based on the drama Strakonický dudák aneb Hody divých žen (The Bagpiper of Strakonice) by Josef Kajetán Tyl.

At the time the opera, with its occasional use of Czech folk material, enjoyed considerable success, with translations into 17 languages. The opera fell from the repertory when the composer’s music was banned by the Nazi regimes of Austria and Germany during the late 1930s; and although it is still revived occasionally, orchestral performances of the “Polka and Fugue” drawn from the opera are more regularly heard in concert and on record.

From his entry on Wikipiedia,

Bedřich Smetana (1824 -1884) was a Czech composer who pioneered the development of a musical style that became closely identified with his people’s aspirations to a cultural and political “revival.” He has been regarded in his homeland as the father of Czech music. Internationally he is best known for his opera The Bartered Bride and for the symphonic cycle Má vlast (“My Fatherland”), which portrays the history, legends and landscape of the composer’s native Bohemia. It contains the famous symphonic poem “Vltava”, also popularly known by its German name “Die Moldau” (in English, “The Moldau”).

By the end of 1874, Smetana had become completely deaf but, freed from his theatre duties and the related controversies, he began a period of sustained composition that continued for almost the rest of his life. His contributions to Czech music were increasingly recognised and honoured, but a mental collapse early in 1884 led to his incarceration in an asylum and subsequent death. Smetana’s reputation as the founding father of Czech music has endured in his native country, where advocates have raised his status above that of his contemporaries and successors. However, relatively few of Smetana’s works are in the international repertory, and most foreign commentators tend to regard Antonín Dvořák as a more significant Czech composer.

Don’t any of these stories end well?

From his entry on Wikipedia,

Antonín Leopold Dvořák (1841-1904) was a Czech composer, one of the first to achieve worldwide recognition. Following the Romantic-era nationalist example of his predecessor Bedřich Smetana, Dvořák frequently employed rhythms and other aspects of the folk music of Moravia and his native Bohemia. Dvořák’s own style has been described as “the fullest recreation of a national idiom with that of the symphonic tradition, absorbing folk influences and finding effective ways of using them”

All of Dvořák’s nine operas, except his first, have librettos in Czech and were intended to convey the Czech national spirit, as were some of his choral works. By far the most successful of the operas is Rusalka. Among his smaller works, the seventh Humoresque and the song “Songs My Mother Taught Me” are also widely performed and recorded. He has been described as “arguably the most versatile… composer of his time”.

The Dvořák Prague International Music Festival is a major series of concerts held annually to celebrate Dvořák’s life and works.

From its entry on Wikipedia,

The concert overture Carnival (Czech: Karneval, koncertní ouvertura), Op. 92, B. 169, was written by Antonín Dvořák in 1891. It is part of a “Nature, Life and Love” trilogy of overtures, forming the second part, “Life”. The other two parts are In Nature’s Realm, Op. 91 (“Nature”) and Othello, Op. 93 (“Love”).

The Subjective Stuff

Recording quality: 4

Overall musicianship: 5

CD booklet notes: 2.5

CD “album cover” information: 2.5

How does this make me feel: 5

I didn’t think I was going to like this CD. After all, it is Mr. Showboat himself (Tchaikovsky) kicking things off.

But I found myself drawn into these performances, finding something worthwhile in each of them – be in the unbridled exuberance of the 1812 Overture, or in the bouncy pizzicato in the reel-like Mephisto Waltz, or the joyful circus-like thrill ride known as the Polka and Fugue, or the sweeping grandeur (shades of an old-West musical score, or a piece of music by Aaron Copeland) of The Bartered Bride, or the whirlwind of wonder from Dvorak called Carnival Overture.

I was engaged. Seriously. It takes a lot to get me to this point. But once my mind is invested, my heart almost always follows suit. I even enjoyed listening to the 1812 Overture, hearing things in it that I’d never noticed before, such as La Marseillaise, the French national anthem.

For being over 60 years old, these recordings were compelling. Huzzah! to the sound techs, then and now.

I’d listen to this CD again (and have, some four times now).