I’m surprised and pleased! This morning’s CD is much more enjoyable than yesterday’s.

The performances sound better to me.

At least, they’re more robust than what I heard yesterday.

Woo-hoo!

There are a couple of items from Kenneth Morgan’s book Fritz Reiner Maestro & Martinet that I’d like to mention.

First, this from page 214:

Where legitimate alternatives to instrumentation were marked by composers, Reiner made a clear choice, but he did not always follow a composer’s later thoughts. He used clarinets in the revised version of Mozart’s Symphony No. 40 possible because, as Richard Freed explains, “Reiner opted for the clarinets, as most of his contemporaries did, regarding the addition as Mozart’s final thought on the work.” Since the clarinet was a relatively new instrument in Mozart’s time, Reiner may have surmised that the composer would not include parts for it if he did not intend it to play.

And this, from page 216:

Reiner was, relatively speaking, a purist in keeping to the composer’s wishes as given in a score. He thought conductors should always adhere faithfully to the score in the great classics; otherwise, it would be unclear where to draw the line with adaptations. Individuality of interpretation in this repertoire should observe certain limits. To try something startlingly original with well-known scores might be to misquote great art, and that woiuld be nothing short of criminal.

Given Reiner’s perfectionist (even “martinet”) personality, I’d expect no less, really. And, frankly, why would we want “startlingly original” interpretations from a conductor? I don’t want some clown’s opinions from today to change the way the great composers wrote their works centuries ago. If such approaches became the norm, we’d never know what great music actually sounded like. It would lose its original form, and would, eventually, disintegrate into whatever conductors and orchestras felt like playing on any given day.

Can you imagine Beethoven’s 9th with a Disco beat? (Sort of like Ludwig meets the Bee Gees.) Or Mozart’s Don Giovanni with a Harry Connick, Jr, voice instead of Eberhard Wächter? (Wolfgang meets Sinatra.) Where would it all stop?

I realize Walter Murphy composed a song in 1976 called “A Fifth of Beethoven” in which he mashed Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony with a disco beat.

But everyone knows that’s a novelty, a lark. It’s a song that couldn’t exist without Beethoven first composing his Fifth and then the decade of the ’70s providing the Disco beat. And it’s certainly not that listenable today.

Murphy’s album A Fifth of Beethoven offers up 10 songs, several of which are Classical mashups with Disco music. You can hear it here. It’s groovy stuff. But I seriously doubt anyone’s going to be listening to the Disco version of Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1 (Murphy’s “Russian Dressing”) a century and a half from now. Like dinosaurs, there’s a reason why Disco died.

So, if I was a conductor, I’d play Classical music as painstakingly close to what most historians and conductors thought it was supposed to sound like as I possibly could. Playing notes that were written three centuries before I was born would be thrill enough. I wouldn’t need to jazz it up any more to make it exciting.

But that’s just me.

The Objective Stuff

Mozart’s Symphony No. 40, according to its entry on Wikipedia,

…was written by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in 1788. It is sometimes referred to as the “Great G minor symphony”, to distinguish it from the “Little G minor symphony”, No. 25. The two are the only extant minor key symphonies Mozart wrote.

The date of completion of this symphony is known exactly since Mozart in his mature years kept a full catalog of his completed works; he entered the 40th Symphony into it on 25 July 1788. Work on the symphony occupied an exceptionally productive period of just a few weeks during which time he also completed the 39th and 41st symphonies (26 June and 10 August, respectively).

Mozart was 32 when he completed his 40th.

Mozart’s Symphony No. 41, according to its entry on Wikipedia,

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart completed his Symphony No. 41 in C major, K. 551, on 10 August 1788. The longest and last symphony that he composed, it is regarded by many critics as among the greatest symphonies in classical music. The work is nicknamed the Jupiter Symphony, likely coined by the impresario Johann Peter Salomon.

It is not known whether Symphony No. 41 was ever performed in the composer’s lifetime. According to Otto Erich Deutsch, around this time Mozart was preparing to hold a series of “Concerts in the Casino” in a new casino in the Spiegelgasse owned by Philipp Otto. Mozart even sent a pair of tickets for this series to his friend Michael Puchberg. But it seems impossible to determine whether the concert series was held, or was cancelled for lack of interest.

Symphony No. 40 was recorded in mono at Orchestra Hall, Chicago, on April 25, 1955. Reiner was about 67. Symphony No. 41 was recorded in stereo at Orchestra Hall on April 26, 1954, but released as a mono LP. Reiner was about 66.

The Subjective Stuff

Recording quality: 3 (Symphony No. 40) / 4.5 (Symphony No. 41)

Overall musicianship: 3 (Symphony No. 40) / 4.5 (Symphony No. 41)

CD booklet notes: 2

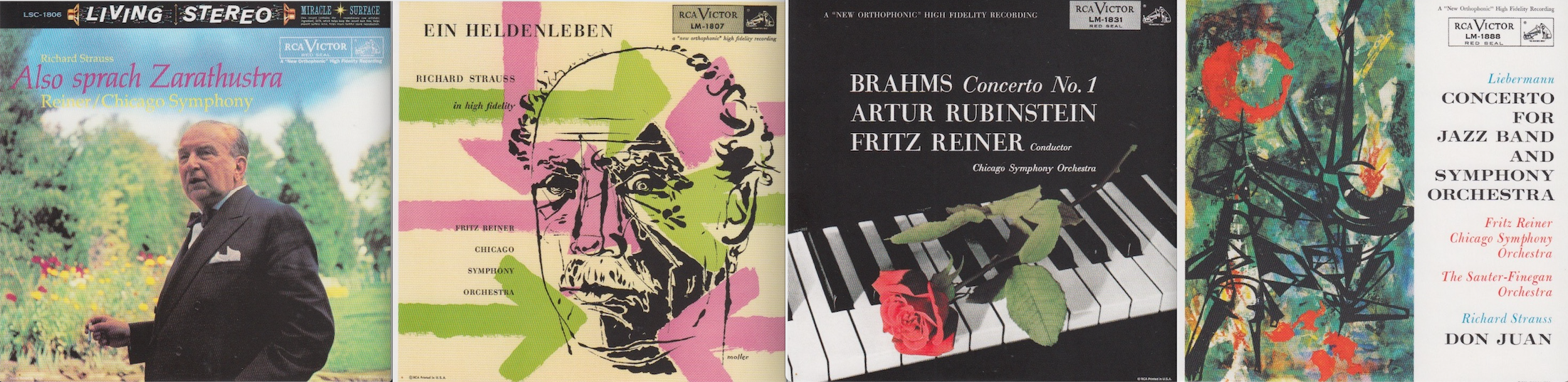

CD “album cover” information: 0 (the back is as blank as the Beatles’ White Album)

How does this make me feel: 4 (Symphony No. 40) / 4 (Symphony No. 41)

It’s hard to beat the first movement of Symphony No. 40. It’s big, grand, and universally recognized for its construction. I probably would have like it a lot better, though, if the recording didn’t sound so bland. The mono recordings on the RCA label have not been anything to write home about. (And I don’t know who’d be there to receive my letter, anyway; I haven’t lived at home for 40 years. And what would be the point of mailing a letter to myself at this home. I’m already here!)

A better recording is Symphony No. 41, but it’s a less engaging composition. Or maybe it’s the performance. It’s not electrifying like “Jupiter” should be. It’s good. But it lacks energy.

I wonder if I’m discovering “the Reiner sound” (the name of the 24th album in this set) for myself: Maximum competence. A perfectly executed, highly contained performance. But nothing passionate or flamboyant.

The hell do I know? I’m not a conductor. Or even a musician.

But I have listened to hundreds of hours (over hundreds of days) worth of Classical music in my life. I know when something feels electrifying, and when it doesn’t.

As much as I like Mozart, I seriously doubt I’d use this album to introduce people to Mozart’s music. It’s just not remarkable.