As I might have mentioned before, I’m not really a fan of Brahms. I realize his one of the big B composers (Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms).

But I’m not that fond of Bach, either.

So there.

For a Living Stereo recording, this sounds unusually flat.

Maybe my ears are getting old (and why not? since the rest of my body is, I’m pretty sure my ears are, too). But I’m not hearing a lot of depth and lushness here. Emil Gilel’s piano work stands out. But the rest of the orchestra sounds kind of mushed together.

Don’t get me wrong. This isn’t a bad recording. I’m not suggesting or even stating that. But I’ve heard more “alive” sounding Living Stereo recordings in my day.

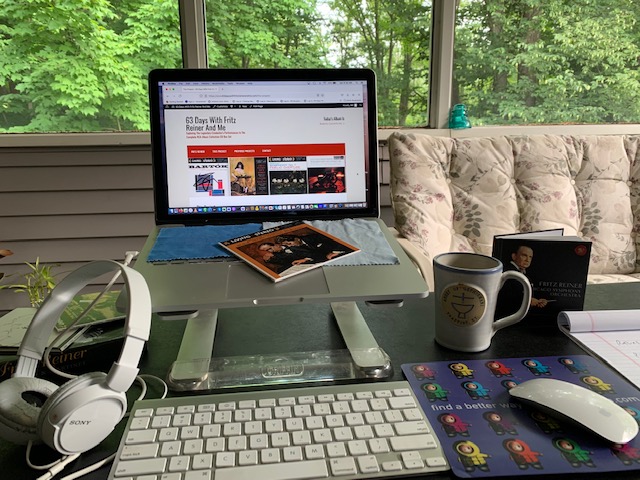

It’s a good thing I’m enjoying the beautiful weather on the screen-in porch, a cuppa Joe beside me.

Otherwise, I might not feel so kindly toward Johannes.

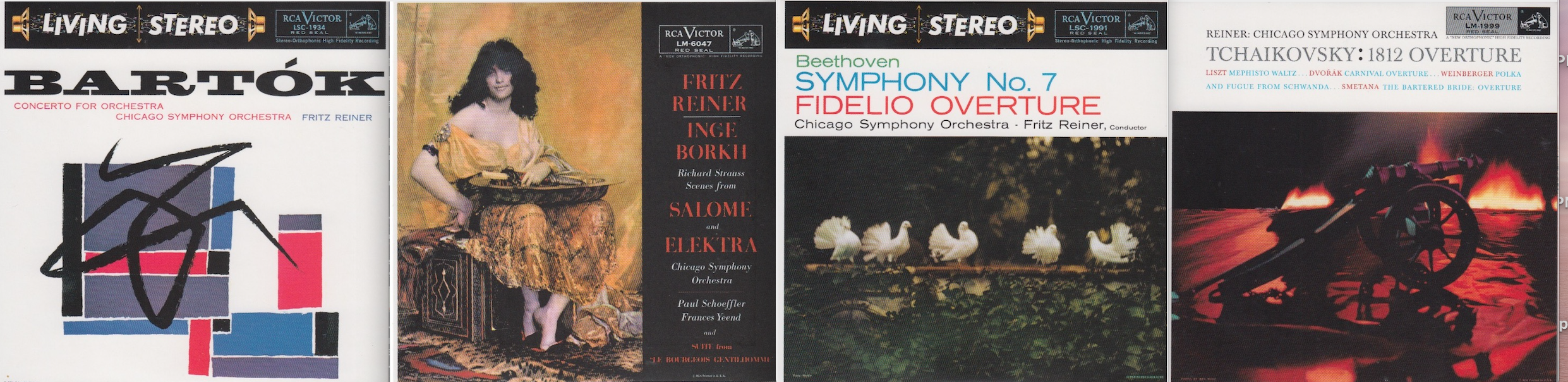

The Objective Stuff

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897), according to his entry on Wikipedia,

…was a German composer, pianist, and conductor of the Romantic period. Born in Hamburg into a Lutheran family, he spent much of his professional life in Vienna. He is sometimes grouped with Johann Sebastian Bach and Ludwig van Beethoven as one of the “Three Bs” of music, a comment originally made by the nineteenth-century conductor Hans von Bülow.

Brahms composed for symphony orchestra, chamber ensembles, piano, organ, voice, and chorus. A virtuoso pianist, he premiered many of his own works. He worked with leading performers of his time, including the pianist Clara Schumann and the violinist Joseph Joachim (the three were close friends). Many of his works have become staples of the modern concert repertoire.

Brahms has been considered both a traditionalist and an innovator, by his contemporaries and by later writers. His music is rooted in the structures and compositional techniques of the Classical masters. While some contemporaries found his music to be overly academic, his contribution and craftsmanship were admired by subsequent figures as diverse as Arnold Schoenberg and Edward Elgar. The diligent, highly constructed nature of Brahms’s works was a starting point and an inspiration for a generation of composers. Embedded within those structures are deeply romantic motifs.

According to its entry on Wikipedia,

The Piano Concerto No. 2 in B♭ major, Op. 83, by Johannes Brahms is separated by a gap of 22 years from his first piano concerto. Brahms began work on the piece in 1878 and completed it in 1881 while in Pressbaum near Vienna. It took him three years to work on this concerto which indicates that he was always self-critical. He wrote to Clara Schumann: “I want to tell you that I have written a very small piano concerto with a very small and pretty scherzo.” Ironically, he was describing a huge piece. This concerto is dedicated to his teacher, Eduard Marxsen. The public premiere of the concerto was given in Budapest on 9 November 1881, with Brahms as soloist and the Budapest Philharmonic Orchestra, and was an immediate success. He proceeded to perform the piece in many cities across Europe.

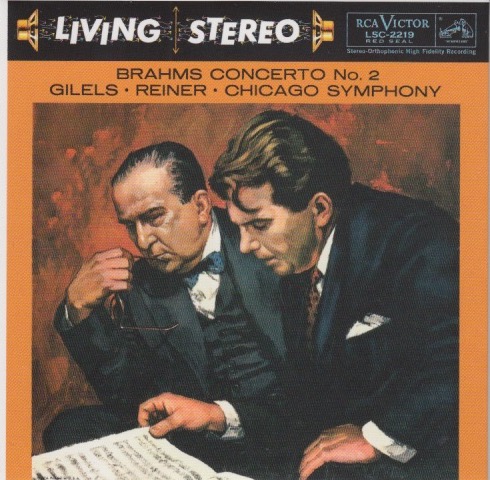

Brahms was 45-48 years old when he composed this piece of music. Emil Gilels (1916-1985) was the pianist for this performance. Janos Starker (1924-2013) played the cello. I’d never heard of Mr. Starker. So I looked him up. According to his entry on Wikipedia,

János Starker (1924 – 2013) was a Hungarian-American cellist. From 1958 until his death, he taught at the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, where he held the title of Distinguished Professor. Starker is considered one of the greatest cellists of all time.

Starker made his professional debut at age 14, playing the Dvořák concerto with three hours’ notice when the originally scheduled soloist was unable to play. He left the Liszt Academy in 1939 and spent most of the war in Budapest. Because of his youth, Starker escaped the tragic fate of his older brothers, who were pressed into forced labor and eventually murdered by the Nazis. Starker nevertheless spent three months in a Nazi internment camp.

From 1950 to 1965, Starker played and recorded on the Lord Aylesford Stradivarius, the largest instrument made by Antonio Stradivarius. In 1965 Starker acquired a Matteo Goffriller cello believed to have been made in Venice in 1705; known previously as the “Ivor James Goffriller” cello, Starker renamed it for its certification as “The Star” cello.

I hate Nazis.

But I love people who have overcome tremendous hardship to create such beautiful music. The cello playing in this concerto is exquisite.

Reiner was around 70 when he conducted this performance.

The Subjective Stuff

Recording quality: 3.5

Overall musicianship: 3.5

CD booklet notes: 2

CD “album cover” information: 4.0

How does this make me feel: 3.5

Brahms, to me, is too sleepy. Too sedate. Not magical, mystical, mysterious, or even overly melodic. It’s like what I’d compose, if I could compose at all. By that last bit, I mean I play guitar. But I can only mimic what others have created. I could never be a songwriter, a composer, a creator of music. If I was, I’d probably be mediocre.

That’s Brahms.

I realize he was one of the greats, one of of the Three Bs. Yes, yes, yes. I get that.

But he doesn’t do anything for me.

That’s what it all comes down to, isn’t it? Music is highly subjective, and – like art – is in the eye (in this case, the ear) of the beholder.

I like Mozart, Beethoven, Bruckner, a little Bach, a little (very, very little) Haydn, Chopin. I’ve recently (thanks to this Reiner project) discovered I like Ravel, and Stravinsky, and Rachmaninoff, as well. But all of those composers have something in common: they appeal to me. That’s it. I could probably analyze all the reasons why. But, in the end, it’s not a graph on which I can plot quality and accessibility or enjoyment. Something about Beethoven, Bruckner, and Mozart resonates with me.

Brahms does not resonate with me.

That doesn’t mean Brahms is a hack. It just means he’s not for me.

That written, that are passages of these four movements that I enjoyed – notably, the French horns (one of my favorite instruments), the piano (although Emil doesn’t immediately jump out at me the way Rubinstein or Byron Janis does), and the bold, crashing sound of the first movement (Allegro Non Troppo). Movement I is my favorite.

This is okay music. But life is too short to hear “okay music” on more than one occasion.