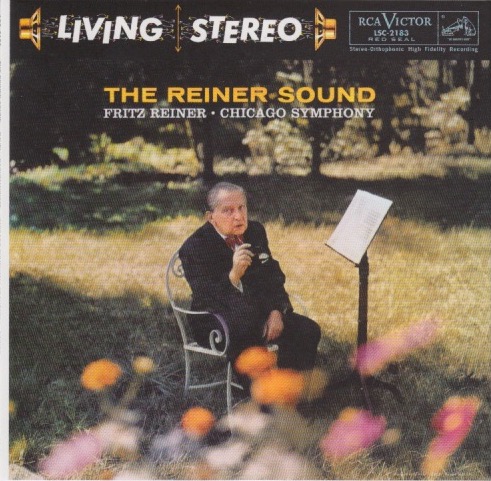

The first thing that came to my mind when I saw the title of today’s CD was, “The Reiner Sound? Probably an orchestra full of musicians crying because of the verbal flogging he gives them.”

But then I thought that would be mean of me.

So I didn’t say it.

As for today’s album, I must say I was hooked from the first few minutes.

Maybe it’s my mood this morning. I mean, the weather is gorgeous.

The windows and porch doors are open.

I have a fresh cup of coffee (“White Heather” – a velvety smooth brew with a hint of butterscotch) beside me. Pair that with a toasted, unfrosted blueberry Pop-Tart slathered with butter and your taste buds will do the conga.

I am alone here, no one around with whom to chit chat. Just me and my thoughts.

And the Reiner Sound.

I was familar with both composers (Ravel and Rachmaninoff) on today’s album. But I wasn’t familiar with the word “pavan.” So…

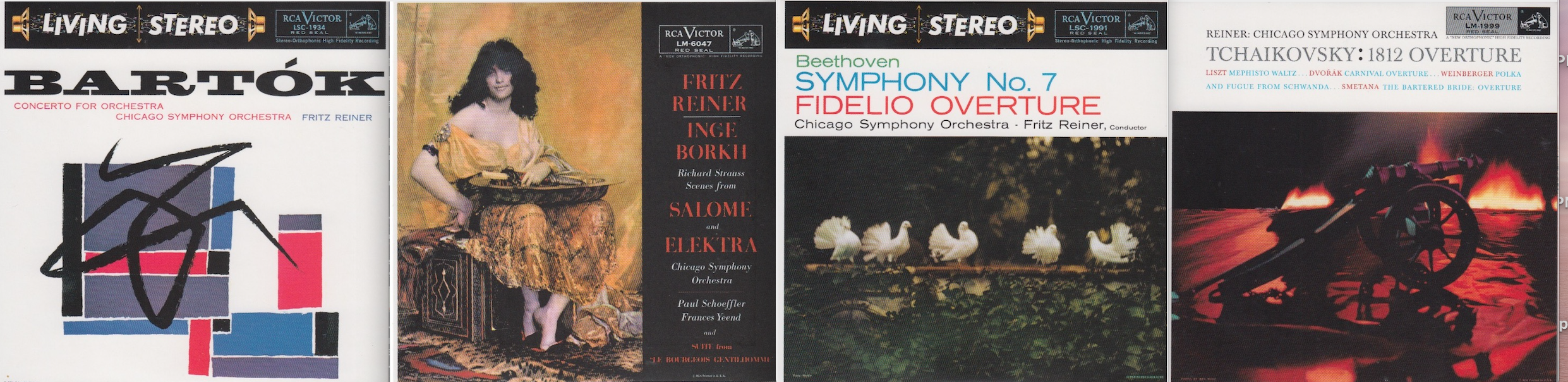

The Objective Stuff

That may be because, contrary to what it reads on the back of the album jacket, the word is not “pavan.” It’s “pavane.” According to its entry on Wikipedia,

The pavane is a slow processional dance common in Europe during the 16th century (Renaissance).

The pavane, the earliest-known music for which was published in Venice by Ottaviano Petrucci, in Joan Ambrosio Dalza’s Intabolatura de lauto libro quarto in 1508, is a sedate and dignified couple dance, similar to the 15th-century basse danse. The music which accompanied it appears originally to have been fast or moderately fast but, like many other dances, became slower over time.

The decorous sweep of the pavane suited the new more sober Spanish-influenced courtly manners of 16th-century Italy. It appears in dance manuals in England, France, and Italy.

The pavane’s popularity was from roughly 1530 to 1676, though, as a dance, it was already dying out by the late 16th century.. As a musical form, the pavan survived long after the dance itself was abandoned, and well into the Baroque period, when it finally gave way to the allemande/courante sequence.

Well, gee whiz. How am I supposed to know what the words are on the back of the album jacket if they’re not correct in the first place?

As for its composer, Maurice Ravel, here what his entry on Wikipedia had to say about him,

Joseph Maurice Ravel (1875 – 1937) was a French composer, pianist and conductor. He is often associated with impressionism along with his elder contemporary Claude Debussy, although both composers rejected the term. In the 1920s and 1930s Ravel was internationally regarded as France’s greatest living composer.

Born to a music-loving family, Ravel attended France’s premier music college, the Paris Conservatoire; he was not well regarded by its conservative establishment, whose biased treatment of him caused a scandal. After leaving the conservatoire, Ravel found his own way as a composer, developing a style of great clarity and incorporating elements of modernism, baroque, neoclassicism and, in his later works, jazz. He liked to experiment with musical form, as in his best-known work, Boléro (1928), in which repetition takes the place of development. Renowned for his abilities in orchestration, Ravel made some orchestral arrangements of other composers’ piano music, of which his 1922 version of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition is the best known.

A slow and painstaking worker, Ravel composed fewer pieces than many of his contemporaries. Among his works to enter the repertoire are pieces for piano, chamber music, two piano concertos, ballet music, two operas and eight song cycles; he wrote no symphonies or church music.

According to its entry on Wikipedia, here’s what the people who write Wiki articles say about his composition Pavan [sic] For a Dead Princess.

Pavane pour une infante défunte (Pavane for a Dead Princess) is a work for solo piano by Maurice Ravel, written in 1899 while the French composer was studying at the Conservatoire de Paris under Gabriel Fauré. Ravel published an orchestral version in 1910 using two flutes, an oboe, two clarinets (in B♭), two bassoons, two horns, harp, and strings.

Ravel described the piece as “an evocation of a pavane that a little princess [Infanta] might, in former times, have danced at the Spanish court”. The pavane was a slow processional dance that enjoyed great popularity in the courts of Europe during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

This antique miniature is not meant to pay tribute to any particular princess from history, but rather expresses a nostalgic enthusiasm for Spanish customs and sensibilities, which Ravel shared with many of his contemporaries (most notably Debussy and Albéniz) and which is evident in some of his other works such as the Rapsodie espagnole and the Boléro.

I kind of got ahead of myself. The “pavan” is the second performance on today’s CD. The first, also by Ravel, is Rapsodie Espagnole, which – according to its entry on Wikipedia – is,

…is an orchestral rhapsody written by Maurice Ravel. Composed between 1907 and 1908, the Rapsodie is one of Ravel’s first major works for orchestra. It was first performed in Paris in 1908 and quickly entered the international repertoire. The piece draws on the composer’s Spanish heritage and is one of several of his works set in or reflecting Spain.

The genesis of the Rapsodie was a Habanera, for two pianos, which Ravel wrote in 1895. It was not published as a separate piece, and in 1907 he composed three companion pieces. A two-piano version was completed by October of that year, and the suite was fully orchestrated the following February. At about this time there was a distinctly Spanish tone to Ravel’s output, perhaps reflecting his own Spanish ancestry. His opera L’heure espagnole was completed in 1907, as was the song “Vocalise-Etude en forme de habanera”.

Finally, there is Rachminoff’s Isle of the Dead, which – according to its entry on Wikipedia – is,

…a symphonic poem composed by Sergei Rachmaninoff, written in the key of A minor. He concluded the composition while staying in Dresden in 1908. It is considered a classic example of Russian late-Romanticism of the beginning of the 20th century.

The piece was inspired by a black and white reproduction of Arnold Böcklin’s painting, Isle of the Dead, which Rachmaninoff saw in Paris in 1907. Rachmaninoff was disappointed by the original painting when he later saw it, saying, “If I had seen first the original, I, probably, would have not written my Isle of the Dead. I like it in black and white.”

Fascinating.

Regarding the painting itself, here’s what its entry on Wikipedia has to say about it,

Isle of the Dead (German: Die Toteninsel) is the best-known painting of Swiss Symbolist artist Arnold Böcklin (1827–1901). Prints were very popular in central Europe in the early 20th century—Vladimir Nabokov observed in his 1936 novel Despair that they could be “found in every Berlin home”.

Böcklin produced several different versions of the painting between 1880 and 1901, which today are exhibited in Basel, New York City, Berlin and Leipzig.

All versions of Isle of the Dead depict a desolate and rocky islet seen across an expanse of dark water. A small rowing boat is just arriving at a water gate and seawall on shore. An oarsman maneuvers the boat from the stern. In the bow, facing the gate, is a standing figure clad entirely in white. Just ahead of the figure is a white, festooned object commonly interpreted as a coffin. The tiny islet is dominated by a dense grove of tall, dark cypress trees—associated by long-standing tradition with cemeteries and mourning—which is closely hemmed in by precipitous cliffs. Furthering the funerary theme are what appear to be sepulchral portals and windows on the rock faces.

Böcklin himself provided no public explanation as to the meaning of the painting, though he did describe it as “a dream picture: it must produce such a stillness that one would be awed by a knock on the door”.

Double fascinating.

Okay. So I learned many things from this information, chiefly that Russian novelist named Vladimir Nabokov (1899-1977) wrote a book in 1936 called Despair, in which he mentions Böcklin’s painting.

Nabokov is an interesting fellow in his own right. According to his entry on Wikipedia,

Nabokov was a self-described synesthete, who at a young age equated the number five with the colour red. Aspects of synesthesia can be found in several of his works. His wife also exhibited synesthesia; like her husband, her mind’s eye associated colours with particular letters. They discovered that Dmitri shared the trait, and moreover that the colours he associated with some letters were in some cases blends of his parents’ hues—”which is as if genes were painting in aquarelle”.

For some synesthetes, letters are not simply associated with certain colors, they are themselves colored. Nabokov frequently endowed his protagonists with a similar gift. In Bend Sinister Krug comments on his perception of the word “loyalty” as being like a golden fork lying out in the sun. In The Defense, Nabokov mentioned briefly how the main character’s father, a writer, found he was unable to complete a novel that he planned to write, becoming lost in the fabricated storyline by “starting with colors”. Many other subtle references are made in Nabokov’s writing that can be traced back to his synesthesia. Many of his characters have a distinct “sensory appetite” reminiscent of synesthesia.

Nabokov was a notorious, lifelong insomniac who admitted unease at the prospect of sleep, famously stating that “the night is always a giant”. His insomnia contributed to an enlarged prostate later in life, which only exacerbated his sleeplessness. Nabokov called sleep a “moronic fraternity”, “mental torture”, and a “nightly betrayal of reason, humanity, genius”. Insomnia’s impact on his work was widely explored and in 2017 Princeton University Press published a compilation of his dream diary entries, Insomniac Dreams: Experiments with Time by Vladimir Nabokov.

Triple fascinating.

All performances were recorded at Orchestra Hall, Chicago. Rapsodie Espagnole was recorded on November 3, 1956. Pavane For a Dead Princess was recorded on March 2, 1957. Isle of the Dead was recorded on April 13, 1957.

Ravel was 32-33 when he composed Rhapsodie. He was 24 when he composed Pavane. Rachmaninoff was 35 when he composed Isle. Reiner was 68 or 69 when he conducted these pieces.

The Subjective Stuff

Recording quality: 4.5

Overall musicianship: 5

CD booklet notes: 2

CD “album cover” information: 4.5

How does this make me feel: 5

This entire album is fascinating, compelling, lyrical, and magical. It was well recorded, with a lush depth and texture.

As I wrote at the outset, I was drawn in from the beginning (Rhapsodie), and only wavered in my enthusiasm for this album slightly when I got to the third performance (Isle of the Dead). I definitely got the funereal vibe. But therein lies my quibble. I’m not a fan of lugubrious music.

I enjoyed listening to this album. I enjoyed reading about the compositions. I enjoyed reading about Russian author Vladimir Nabokov – who, incidentally, wrote the novel Lolita.

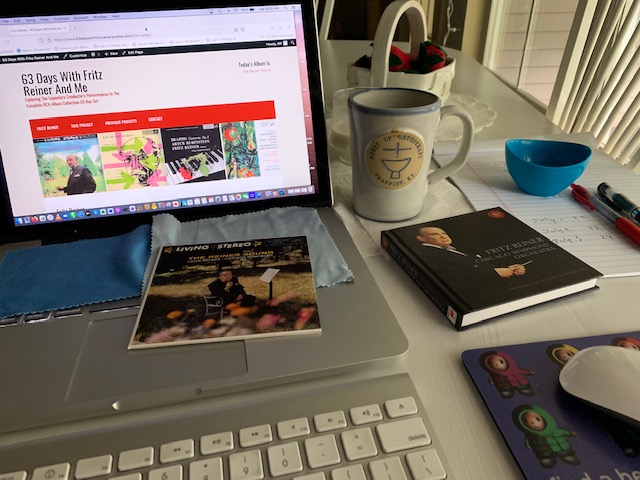

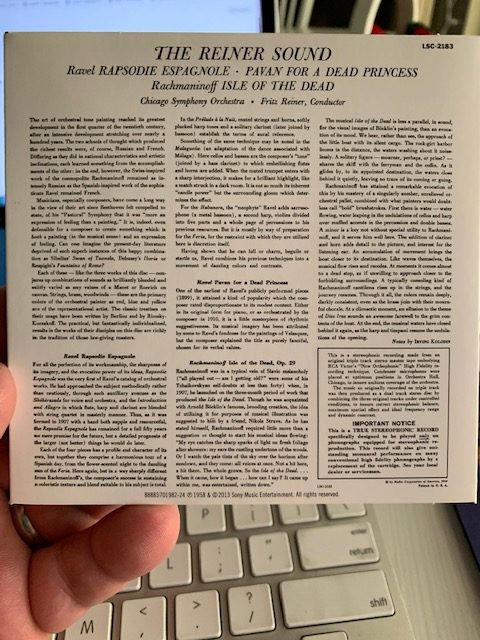

By the way, the notes on the back of the album cover were extensive and informative.

They’re tiny, though.

And I couldn’t find my magnifying glass.

So I took a picture with my phone, e-mailed it to myself, and used the enlarge tool on my laptop to read the words.

The music on this album isn’t really the kind that I could share with anyone, however. It’s not that engaging unless one is also involved with (and enjoys) the research behind the compositions and composers.

For me, that’s the beauty of these projects. I learn a great deal about what went on behind the composing – and, to paraphrase Frost, that has made all the difference. Knowing the background enhances the listening.