On this rainy, muggy Thursday morning in July, I’m at my usual spot at the local eatery – the one that features god-awful music, Light Roast coffee, and an Asiago Bagel (toasted twice!) with plain cream cheese – this time listening to Antonín Dvořák New World Symphony.

It’s not bad.

All of it.

Even the rain is a welcome respite from the 90-degree weather we’ve had lately.

Like the shirts I wear, Life is Good.

As I sit here, listening to Symphony No. 5, in E Minor, Op. 95 (which is the official name of Dvorak’s symphony also known as “From the New World”), I watch a couple of mourning doves hopping along on the pavement, obviously looking for scraps of food.

I often ponder the life of a bird – or any wild creature, really.

Talk about a hard life.

Every day, they have to forage for food, and lots of it – sometimes, to share with their waiting offspring; sometimes, to eat themselves. Either way, obtaining that much food, every day, has to be difficult.

Which is why I sometimes feel sorry for creatures in the wild – even though I realize they have no concept of “sorry.” I doubt they’re even self aware. So it’s a sure bet they’re not sitting around thinking, “I’m screwed if I don’t get five more worms.”

But more than once my wife and I will drive by a pond or stream and see a Great Blue Heron wading in the water near the shore, looking for food to stab with its very long beak. (We call such birds “stabbies” because of that.) The stand motionless, waiting. Slowly walking. And waiting. Waiting.

Suddenly, the stabbie bird will lunge into the water and come up, sometimes with something in its beak, usually not. We root for the stabbie birds, hoping there’s something lurking under the surface of the water that would make a nice meal for them. But how much freakin’ food does a bird that size need to stab to survive?

A running joke of mine is that when I get to heaven I’m going to sit God down and ask, “What the hell were you thinking? Penguins marching for miles and miles to lay their eggs? Birds with long beaks that have to stab their food? Birds building nests year after year after year? Deer and turkeys and raccoons trying to keep warm and foraging for food in the winter? Just what the hell were you thinking?!?!?”

Of course, I’m also going to sit God down and ask him, “What the hell were you thinking creating human beings with bodies so fragile that they’re prone to breaking down, with the tiniest disruption to our systems (such as a virus or bacteria) enough to kill us? And let’s not even get started on knees. Couldn’t you have made knees that didn’t need to be replaced? And what’s the deal with people’s melons perched on top of their necks – the most essential part of a person’s body resting on a neck like a golf ball on a tee?!?! Could this entire organism be any more fragile?!?!?!”

I envision doing a lot of sitting down with God.

Of course, the reality is I’m likely to get my ass spanked by the Big Man.

But that’s neither here nor there.

This morning, I’m listening to – and actually thoroughly enjoying – “From the New World.”

The Objective Stuff

From his entry on Wikipedia,

Antonín Leopold Dvořák (1841 – 1904) was a Czech composer, one of the first to achieve worldwide recognition. Following the Romantic-era nationalist example of his predecessor Bedřich Smetana, Dvořák frequently employed rhythms and other aspects of the folk music of Moravia and his native Bohemia. Dvořák’s own style has been described as “the fullest recreation of a national idiom with that of the symphonic tradition, absorbing folk influences and finding effective ways of using them”.

Dvořák displayed his musical gifts at an early age, being an apt violin student from age six. The first public performances of his works were in Prague in 1872 and, with special success, in 1873, when he was 31 years old. Seeking recognition beyond the Prague area, he submitted a score of his First Symphony to a prize competition in Germany, but did not win, and the unreturned manuscript was lost until rediscovered many decades later. In 1874 he made a submission to the Austrian State Prize for Composition, including scores of two further symphonies and other works. Although Dvořák was not aware of it, Johannes Brahms was the leading member of the jury and was highly impressed. The prize was awarded to Dvořák in 1874 and again in 1876 and in 1877, when Brahms and the prominent critic Eduard Hanslick, also a member of the jury, made themselves known to him. Brahms recommended Dvořák to his publisher, Simrock, who soon afterward commissioned what became the Slavonic Dances, Op. 46. These were highly praised by the Berlin music critic Louis Ehlert in 1878, the sheet music (of the original piano 4-hands version) had excellent sales, and Dvořák’s international reputation was launched at last.

From an article on NPR,

Symphony No. 9 is nicknamed New World because Dvorak wrote it during the time he spent in the U.S. in the 1890s. His experiences in America (including his discovery of African-American and Native-American melodies) and his longing for home color his music with mixed emotions. There’s both a yearning that simmers and an air of innocence.

The music, for me, evokes images. As the symphony opens, I picture Dvorak at the stern of the ship that carries him to America, away from his country. As the land drifts out of sight, he is suddenly jarred by the thought of the unknown with a blast from the French horn.

I can see and hear that. The big, bold melody (DA-da-da-da, da-da-da-da-DUH-da) is introduced in Movement I (Adagio Allegro Molto) and it immediately reminds me of TV shows like How the West Was Won starring James Arness (Matt Dillon of Gunsmoke fame). Or some of the music in a Western comedy film like City Slickers. It’s music used a thousand times in TV shows to depict settlers heading West, looking for – surprise! – the New World.

From its entry on Wikipedia,

The Symphony No. 9 in E minor, “From the New World”, Op. 95, B. 178 (Czech: Symfonie č. 9 e moll “Z nového světa”), popularly known as the New World Symphony, was composed by Antonín Dvořák in 1893 while he was the director of the National Conservatory of Music of America from 1892 to 1895. It premiered in New York City on 16 December 1893. It has been described as one of the most popular of all symphonies. In older literature and recordings, this symphony was – as for its first publication – numbered as Symphony No. 5. Astronaut Neil Armstrong took a tape recording of the New World Symphony along during the Apollo 11 mission, the first Moon landing, in 1969. The symphony was completed in the building that now houses the Bily Clocks Museum.

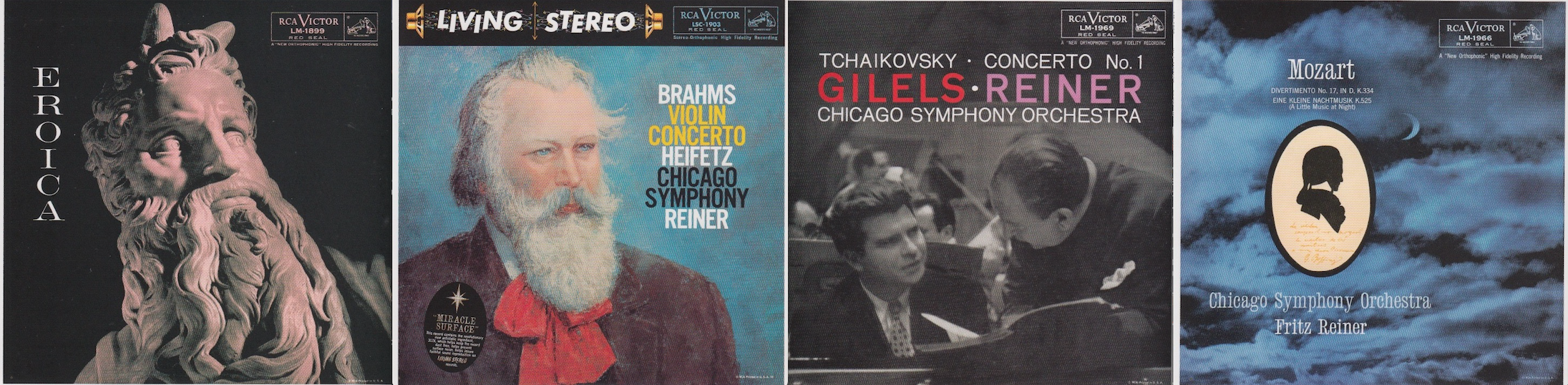

Dvorak was 52 when he composed this piece of music. It was recorded on November 9, 1957, in Orchestra Hall, Chicago. Just for fun, I decided to do something even more “objective” this time. I looked up what day of the week November 9, 1957, was and discovered it was a Saturday. According to The Old Farmer’s Almanac, the average temperature on November 9th in Chicago 28.1 degrees.

So, picture that. It’s a Saturday. The temperature in Chicago is about 28 degrees. You’re inside, part of the world-famous Chicago Symphony Orchestra, playing Dvorak’s New World Symphony, with Fritz Reiner conducting.

What must that have been like?

The Subjective Stuff

Recording quality: 4 (a little tape hiss evident)

Overall musicianship: 5

CD booklet notes: 2

CD “album cover” information: 4.5 (lots and lots of really tiny print)

How does this make me feel: 5

I was completely blown away by this morning’s album.

I had no idea Dvorak was so good!

I loved every one of the four movements, discovering something interesting in each one, from the engaging melodies to the dynamic percussion. Part of this music reminded me of music from a Western TV series or movie. It’s the kind of hope-filled, adventurous music that makes me want to climb into a Conestoga Wagon and point the horses West. The second movement was more melancholy, wistful. And the fourth, well, it was a resounding triumph.

I’ve listened to ‘From the New World” 2-3 times through already. I didn’t get tired of it. In fact, I kept wanting to hear it again.

This one’s a keeper.