If I didn’t like these Asiago bagels (toasted twice!) with plain cream cheese and this bottomless Light Roast coffee so much, and if this particular eatery didn’t open at 6am, I’d pick another listening station for my daily adventure through the Fritz Reiner box set.

Alas. Here I am again.

What I don’t particularly care for is the music they pipe in. I can’t tell what genre this is. But the music has a formula that goes something like this:

- Mind numbingly repetitive chorus that puts the Police (think: “Message in a Bottle”) to shame,

- Typically a male vocalist,

- The vocalist occasionally sings in an improbable falsetto (or a nails-on-chalkboard tenor) with enough overwrought emotion behind it to make me think someone’s squeezing his nuts in the recording studio,

- The subject matter is often about overcoming a breakup (“I will WAIT for you…I will WAIT for you…”), or comparing oneself to an animal – in this case, a coyote (I kid you not),

- Usually stripped down, acoustic instrumentation (guitar or piano being the weapons of choice),

- Often in a tempo just shy of a dirge, with occasional forays into proof of life

And there you have it. Oh, the song rotation may occasionally feature Sheryl Crow telling us she wants to have some fun, or the Cure letting us know that Robert Smith is in love because it’s Friday, or Van Morrison admitting that a moonlight dance is marvelous. But, mostly, these are songs written by people I’d not only never heard of, but hope to never hear of again.

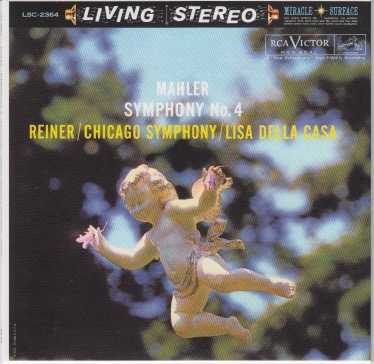

All of which brings me to today’s music: Mahler’s Symphony No. 4 in G.

The Objective Stuff

Here’s where you can read about Gustav Mahler.

From its entry on Wikipedia,

Symphony No. 4 in G major by Gustav Mahler was written in 1899 and 1900, though it incorporates a song originally written in 1892. The song, “Das himmlische Leben”, presents a child’s vision of Heaven. It is sung by a soprano in the work’s fourth and final movement. Although typically described as being in the key of G major, the symphony employs a progressive tonal scheme (‘(b)/G—E’).

Mahler’s first four symphonies are often referred to as the Wunderhorn symphonies because many of their themes originate in earlier songs by Mahler on texts from Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Boy’s Magic Horn). The fourth symphony is built around a single song, “Das himmlische Leben” (“The Heavenly Life”). It is prefigured in various ways in the first three movements and sung in its entirety by a solo soprano in the fourth movement.

Mahler composed “Das himmlische Leben” as a freestanding piece in 1892. The title is Mahler’s own: in the Wunderhorn collection the poem is called “Der Himmel hängt voll Geigen” (an idiomatic expression akin to “there’s not a cloud in the sky”). Several years later Mahler considered using the song as the seventh and final movement of his Symphony No. 3. While motifs from “Das himmlische Leben” are found in the Symphony No. 3, Mahler eventually decided not to include it in that work and, instead, made the song the goal and source of his Symphony No. 4. This symphony thus presents a thematic fulfilment of the musical world of No. 3, which is part of the larger tetralogy of the first four symphonies, as Mahler described them to Natalie Bauer-Lechner. Early plans in which the Symphony was projected as a six-movement work included another Wunderhorn song, “Das irdische Leben” (“The Earthly Life”) as a somber pendant to “Das himmlische Leben”, offering a tableau of childhood starvation in juxtaposition to heavenly abundance, but Mahler later decided on a simpler structure for the score.

From her entry on Wikipedia,

Lisa Della Casa (2 February 1919 – 10 December 2012) was a Swiss soprano most admired for her interpretations of major heroines in operas by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Richard Strauss, and of German lieder. She was also described as “the most beautiful woman on the operatic stage”

Della Casa was born in Burgdorf, Switzerland to an Italian-Swiss father, Francesco Della Casa, and a German mother, Margarete Mueller. She began studying singing at the age of 15 at the Zurich Conservatory, and her teachers included Margarete Haeser.

She made her operatic debut in the title role of Puccini’s Madama Butterfly at Solothurn-Biel Municipal Theater in 1940.

Della Casa sang Pamina in The Magic Flute in 1959. On 26 July 1960, the newly built Großes Festspielhaus in Salzburg opened with a performance of Der Rosenkavalier under Herbert von Karajan. She sang the part of the Marschallin in this performance with Sena Jurinac as Octavian and Hilde Güden as Sophie. Originally, Karajan and film director Paul Czinner planned to make a film of the performance and asked her to perform her role in the film, which she gladly accepted. But due to Walter Legge, well-known recording producer of EMI and husband of Dame Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Della Casa was replaced by Schwarzkopf for the film (a reverse of the 1954 Salzburg Festival production of Mozart’s Don Giovanni, where Schwarzkopf sang in the performances, but was replaced by Della Casa for the film production).

She surprised her audiences by singing the title role in Salome at the Bavarian State Opera House in Munich in 1961. Colleague Inge Borkh said that Della Casa was “very sexy … because she did not seek to be so!” (“Sie war sehr sexy… unbewusst!”)

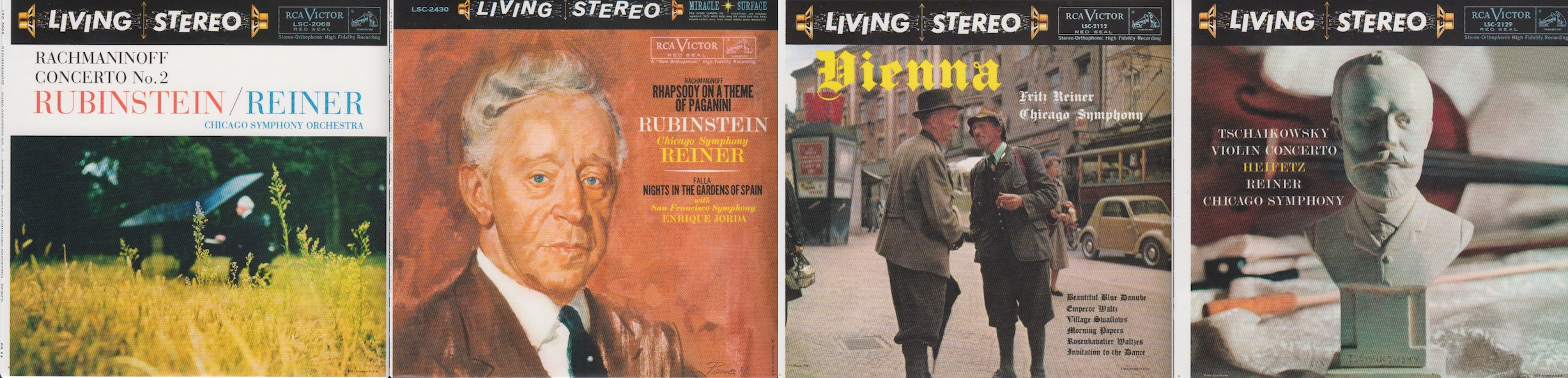

These performances were recorded December 6, 1958, and December 8, 1958, at Orchestra Hall, Chicago. Conductor Reiner was about 70. Mahler was 39 or 40 years old when he completed this symphony.

The Subjective Stuff

Recording quality: 4

Overall musicianship: 4

CD booklet notes: 2

CD “album cover” information: 3 (lots of tiny type)

How does this make me feel: 3.5

I’ve heard a fair bit of Mahler in my day. This was not that bad. The soprano’s voice was not one of my favorites, though. It was in that nails-on-a-chalkboard range. I know she had talent. But her voice did not resonate with me.

But that was only one movement of four. The rest of the movements were Classical-era sounding and well composed.

I’m not sure I’d listen to this again. But it wasn’t horrible to begin with.