This is a challenging CD for me, for a number of reasons.

First, I’m not a big fan of Gustav Mahler.

Second, I’m not a big fan of opera.

Third, I’m not a big fan of Gustav Mahler’s opera.

So I’m listening and gritting my teeth and fighting the urge to leave snide comments on Facebook while I listen and grit my teeth and fight the urge.

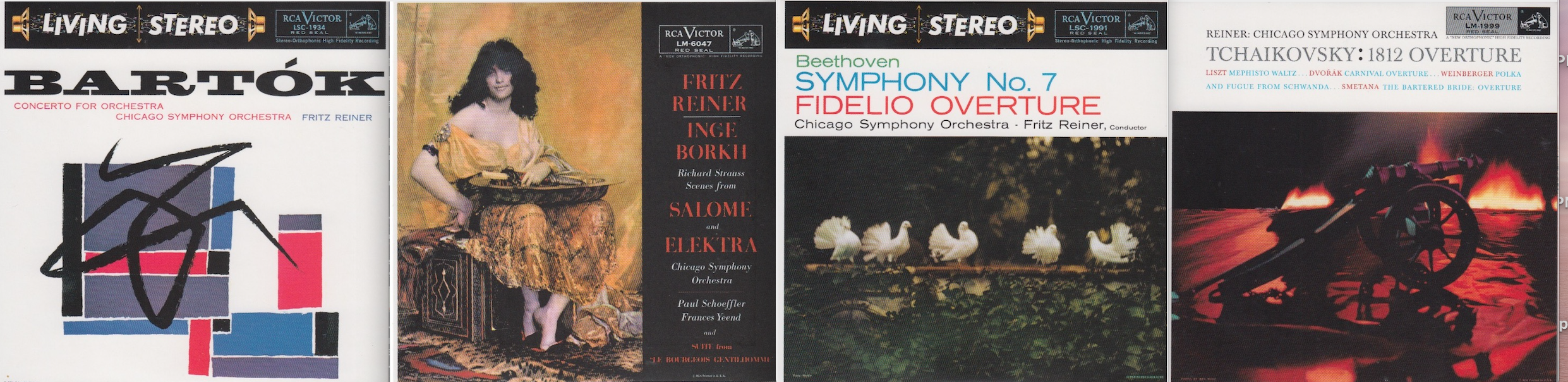

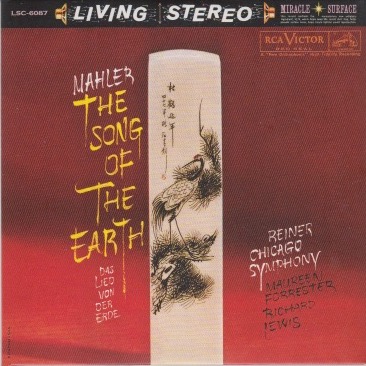

The first thing I noticed about the cover of today’s CD is that the typeface reminds me of that of another, far more famous, album.

I refer, of course, to Pink Floyd’s classic 1979 album The Wall.

Yes. I realize the two fonts are only vaguely similar. But I have a tendency to make mental connections, accurate or not.

The Objective Stuff

From his entry on Wikipedia,

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) was an Austro-Bohemian Romantic composer, and one of the leading conductors of his generation. As a composer he acted as a bridge between the 19th century Austro-German tradition and the modernism of the early 20th century. While in his lifetime his status as a conductor was established beyond question, his own music gained wide popularity only after periods of relative neglect, which included a ban on its performance in much of Europe during the Nazi era. After 1945 his compositions were rediscovered by a new generation of listeners; Mahler then became one of the most frequently performed and recorded of all composers, a position he has sustained into the 21st century. In 2016, a BBC Music Magazine survey of 151 conductors ranked three of his symphonies in the top ten symphonies of all time.

Mahler’s œuvre is relatively limited; for much of his life composing was necessarily a part-time activity while he earned his living as a conductor. Aside from early works such as a movement from a piano quartet composed when he was a student in Vienna, Mahler’s works are generally designed for large orchestral forces, symphonic choruses and operatic soloists. These works were frequently controversial when first performed, and several were slow to receive critical and popular approval; exceptions included his Second Symphony, Third Symphony, and the triumphant premiere of his Eighth Symphony in 1910. Some of Mahler’s immediate musical successors included the composers of the Second Viennese School, notably Arnold Schoenberg, Alban Berg and Anton Webern. Dmitri Shostakovich and Benjamin Britten are among later 20th-century composers who admired and were influenced by Mahler. The International Gustav Mahler Institute was established in 1955 to honour the composer’s life and achievements.

From its entry on Wikipedia,

Das Lied von der Erde (“The Song of the Earth”) is a composition for two voices and orchestra written by the Austrian composer Gustav Mahler between 1908 and 1909. Described as a symphony when published, it comprises six songs for two singers who alternate movements. Mahler specified that the two singers should be a tenor and an alto, or else a tenor and a baritone if an alto is not available. Mahler composed this work following the most painful period in his life, and the songs address themes such as those of living, parting and salvation. On the centenary of Mahler’s birth, the composer and prominent Mahler conductor Leonard Bernstein described Das Lied von der Erde as Mahler’s “greatest symphony”.

Three disasters befell Mahler during the summer of 1907. Political maneuvering and antisemitism forced him to resign as Director of the Vienna Court Opera, his eldest daughter Maria died from scarlet fever and diphtheria, and Mahler himself was diagnosed with a congenital heart defect. “With one stroke,” he wrote to his friend Bruno Walter, “I have lost everything I have gained in terms of who I thought I was, and have to learn my first steps again like a newborn”.

The same year saw the publication of Hans Bethge’s Die chinesische Flöte, a free rewriting of others’ translations of classical Chinese poems. Mahler was captivated by the vision of earthly beauty and transience expressed in these verses and chose seven of the poems to set to music as Das Lied von der Erde. Mahler completed the work in 1909.

Mahler was aware of the so-called “curse of the ninth”, a superstition arising from the fact that no major composer since Beethoven had successfully completed more than nine symphonies: he had already written eight symphonies before composing Das Lied von der Erde. Fearing his subsequent demise, he decided to subtitle the work A Symphony for Tenor, Alto (or Baritone) Voice and Orchestra, rather than numbering it as a symphony. His next symphony, written for purely instrumental forces, was numbered his Ninth. That was indeed the last symphony he fully completed, because only two movements of the Tenth had been fully orchestrated at the time of his death.

Interesting.

From her entry on Wikipedia,

Maureen Kathleen Stewart Forrester, CC OQ (July 25, 1930 – June 16, 2010) was a Canadian operatic contralto.

Maureen Forrester was born and grew up in Montreal, Quebec, one of four children of Thomas Forrester, a Scottish cabinetmaker, and his Irish-born wife, the former May Arnold. She sang in church and radio choirs. At age 13, she dropped out of school to help support the family, working as a secretary at Bell Telephone.[1]

When her brother came home from the war he persuaded her to take singing lessons. She paid for voice lessons with Sally Martin, Frank Rowe, and baritone Bernard Diamant. In the spring of 1951, Forrester appeared on the CBC radio talent competition Opportunity Knocks, singing “Ombra mai fu”, and describing herself to the host as a “starving musician” and part-time switchboard operator. She was ultimately named first runner-up, and later competed on the similar shows Singing Stars of Tomorrow, and Nos Futures Étoiles.

She gave her debut recital at the local YWCA in 1953. She made her concert debut in Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony with the Montreal Symphony Orchestra under Otto Klemperer.

In 1986, she co-authored her autobiography, Out of Character with journalist Marci McDonald.

Maureen Forrester died on June 16, 2010, aged 79, in Toronto, after a long battle with dementia. She was predeceased by Eugene Kash, her former husband, whom she had divorced in 1974, and who died in 2004. She was survived by her five children.

From his entry on Wikipedia,

Richard Lewis CBE (10 May 1914 – 13 November 1990) was an English tenor of Welsh parentage.

Born Thomas Thomas in Manchester to Welsh parents, Lewis began his career as a boy soprano and studied at the Royal Manchester College of Music (now merged into the Royal Northern College of Music) from 1939 to 1941, and later at the Royal Academy of Music. He made his operatic debut in 1939, and from 1947 onwards, sang at the Glyndebourne Festival Opera and at Covent Garden (London). He made his debut in the United States in 1955.

Lewis made a number of recordings, including Messiah (Handel), L’incoronazione di Poppea (Monteverdi), Idomeneo (Mozart), Liebeslieder Walzer and Neue Liebeslieder Walzer (Brahms), Coleridge-Taylor’s The Song of Hiawatha, Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius, Benjamin Britten’s Spring Symphony (with Leonard Bernstein), scenes from William Walton’s Troilus and Cressida, BBC Studio recording of The Mercy of Titus (La Clemenza di Tito) In English with Joan Sutherland, and four different performances of Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde, two with Maureen Forrester, (Reiner/Walter) one with Kathleen Ferrier (Barbirolli), and a fourth with Lili Chookasian (Ormandy). There is also a live recording with George Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra.

In 1963, he was named a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE). He died in Eastbourne in 1990.

And there you have it. Both singers in today’s opera/symphony.

This performance was recorded in Orchestra Hall, Chicago, on two dates, both in 1959: Tracks 1, 3, 5 were recorded on November 9th and tracks 2, 4, 6 were recorded on November 7th. Richard Lewis was about 45. Maureen Forrester was about 29. Conductor Fritz Reiner was in his 71st year.

The Subjective Stuff

Recording quality: 4

Overall musicianship: 4

CD booklet notes: 1

CD “album cover” information: 1 (not one word on the inside, barely a name and titles on the back cover)

How does this make me feel: 1.5

Although I can always appreciate a good tenor, and I can tell Richard Lewis possessed a powerful set of pipes, I was not enamored with this performance. That’s likely partly true because I can never appreciate a contralto singer. A soprano, yes. A coloratura soprano, yes. But the contralto range sounds like nails on a chalkboard to me.

That’s not to say that I don’t think the late Maureen Forrester didn’t have talent, or possess a very fine voice. She obviously had talent. Her voice is probably superb. I just don’t care for it (as my father used to say).

As consequence, today’s performance left me cold.

I’m sorry, Gustav.