Ahhh. This is more like it.

Not even Van Morrison’s unique voice (also an acquired taste) could rattle me as I walked into the bagel-and-coffee restaurant this morning to purchase my usual Asiago bagel (toasted twice!) with plain cream cheese and a mug of Light Roast coffee. (It’s so usual that the person at the counter sees me coming and automatically reaches under the counter for a ceramic mug for my coffee, and reaches behind her and plucks an Asiago bagel out of the rack. It’s almost all ready by the time I get to the register.)

I don’t know what Van was singing. But at least he didn’t sound like someone was squeezes his nuts in the recording studio while he sang it – a welcome change from the usual piped-in music at this restaurant chain.

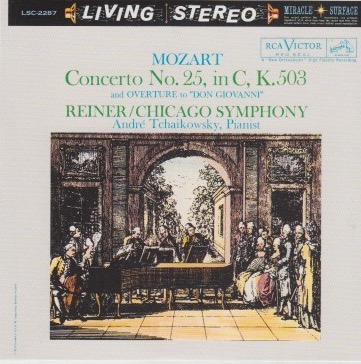

Once I put on my headphones, and Mozart’s Concerto No. 25 washed over me, all was forgiven.

Or was it?

First…

The Objective Stuff

I’ve written about Mozart (1756-1791) on three previous occasions – Day 21, Day 20, and Day 8.

According to its entry on Wikipedia,

The Piano Concerto No. 25 in C major, K. 503, was completed by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart on December 4, 1786, alongside the Prague Symphony, K. 504. Although two more concertos (K. 537 and K. 595) would later follow, this work is the last of what are considered the twelve great piano concertos written in Vienna between 1784 and 1786. Chronologically the work is the 21st of Mozart’s 23 original piano concertos.

K. 503 is now widely recognized as “one of Mozart’s greatest masterpieces in the concerto genre.” However, it had long been neglected in favor of Mozart’s other “more brilliant” concertos, such as K. 467. Though Mozart performed it on several occasions, it was not performed again in Vienna until after his death, and it only gained acceptance in the standard repertoire in the later part of the twentieth century. Mozart’s pupil Johann Nepomuk Hummel valued it, as can be seen in the influence it had on Hummel’s own Piano Concerto in C, Op. 36.

Mozart was 30 when he completed this piece of music.

According to his entry on Wikipedia,

André Tchaikowsky (also Andrzej Czajkowski; born Robert Andrzej Krauthammer; November 1, 1935 – June 26, 1982) was a Polish composer and pianist.

Robert Andrzej Krauthammer was born in Warsaw in 1935 into a Jewish family. He had shown musical talent from an early age, and his mother, an amateur pianist, taught him the piano from the age of four. When the Second World War broke out, they were moved into the Warsaw Ghetto. Krauthammer remained there until 1942, when he was smuggled out and provided with forged identity papers that renamed him Andrzej Czajkowski. He then went into hiding with his grandmother, Celina. The pair remained hidden until 1944, when they were caught up in the Warsaw Uprising, and they were then sent to Pruszków transit camp as ordinary Polish citizens, from which they were released in 1945. Tchaikowsky’s father, Karl Krauthammer, also survived the war, and remarried, producing a daughter, Katherine, later Krauthammer-Vogt. Tchaikowsky’s mother, Felicja Krauthammer (née Rappaport) was confined in the Warsaw Ghetto in 1942, and died in Treblinka.

Andrzej Czajkowski, as he was re-named (he later adopted the spelling André Tchaikowsky), resumed his lessons at age 9 in Lodz State School, under the tuition of Emma Altberg (herself once a student of Wanda Landowska). From there, he went to Paris, where Lazare Lévy took over his musical education, and where he would also break off relations with his father for many years following an argument

Believe it or not, there’s an entry on WIkipedia for Tchaikovsky’s Skull, and it reads this way:

Tchaikowsky died of colon cancer at the age of 46 in Oxford. In his will he left his body to medical research, and donated his skull to the Royal Shakespeare Company, asking that it be used as a prop on stage. Tchaikowsky hoped that his skull would be used for the skull of Yorick in productions of Hamlet. For many years, no actor or director felt comfortable using a real skull in performances, although it was occasionally used in rehearsals. In 2008, the skull was finally held by David Tennant in a series of performances of Hamlet at the Courtyard Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon. After the use of Tchaikowsky’s skull was revealed in the press, this production of Hamlet moved to the West End and the RSC announced that they would no longer use Tchaikowsky’s skull (a spokesman said that it would be “too distracting for the audience”). However, this was a deception; in fact, the skull was used throughout the production’s West End run, and in a subsequent television adaptation broadcast on BBC2. Director Gregory Doran said, “André Tchaikowsky’s skull was a very important part of our production of Hamlet, and despite all the hype about him, he meant a great deal to the company.”

I’ve heard of Haydn’s Head, but not – until now – Tchaikovsky’s Skull.

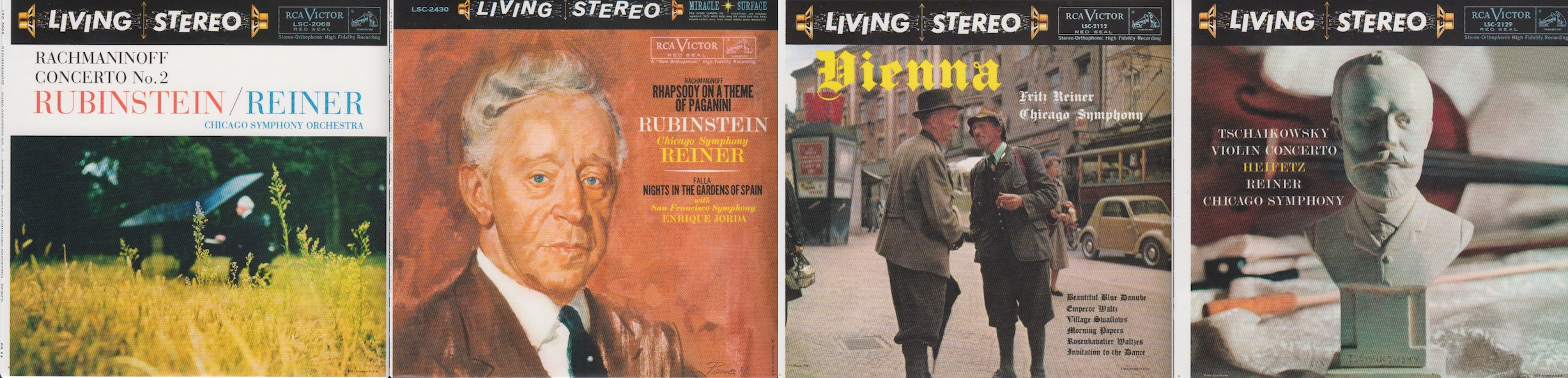

This performance was recorded on February 15, 1958, in Orchestra Hall, Chicago. Maestro Reiner was in his 70th year.

According to its entry on Wikiipedia,

Don Giovanni is generally regarded as one of Mozart’s supreme achievements and one of the greatest operas of all time, and it has proved a fruitful subject for writers and philosophers. A staple of the standard operatic repertoire, it has been described by critic Fiona Maddocks as one of Mozart’s “trio of masterpieces with libretti by Ponte”.

The opera was commissioned after the success of Mozart’s trip to Prague in January and February 1787. The subject may have been chosen due to the genre of eighteenth-century Don Juan opera having originated in Prague.

Lorenzo Da Ponte’s libretto is based on Giovanni Bertati’s for the opera Don Giovanni Tenorio, which premiered in Venice early in 1787. Two important elements he copied were opening the drama with the murder of the Commendatore, and not specifying Seville as the setting. For Bertati, the setting was Villena, Spain, while Da Ponte uses a “city in Spain”.

Don Giovanni was planned to premiere on 14 October 1787 for Archduchess Maria Theresa of Austria’s visit. As the production was not ready Le nozze di Figaro was substituted instead. The score was completed on 28 or 29 October 1787.

Mozart recorded the completion of the opera on 28 October. Some say the overture was completed the day before the premiere, some on the very day.

Mozart was 31 when he composed this overture.

It was recorded on March 14, 1959, at Orchestra Hall, Chicago. Fritz Reiner was in his 71st year.

The Subjective Stuff

Recording quality: 3.5 (piano is recorded very hot, gets pretty loud in my ears)

Overall musicianship: 4

CD booklet notes: 1

CD “album cover” information: 4 (lots of tiny print)

How does this make me feel: 3.5 (Piano Concerto No. 25) / 4 (Overture to Don Giovanni)

Usually, I’m a Mozart freak.

But something about this was off-putting to me. The piano was recorded very loudly and it had a tendency to overpower other instruments. Sometimes, it sounded jarring.

For that reason, I preferred the Overture to Don Giovanni to the Piano Concerto. The Overture was lush, engaging, well recorded, and ended with the kind of dramatic crescendo that left no doubt as to the era in which it was composed.

This is hard for me to write. But I don’t think I’ll be listening to this album again. If I do, it’ll be just the Overture to Don Giovanni.