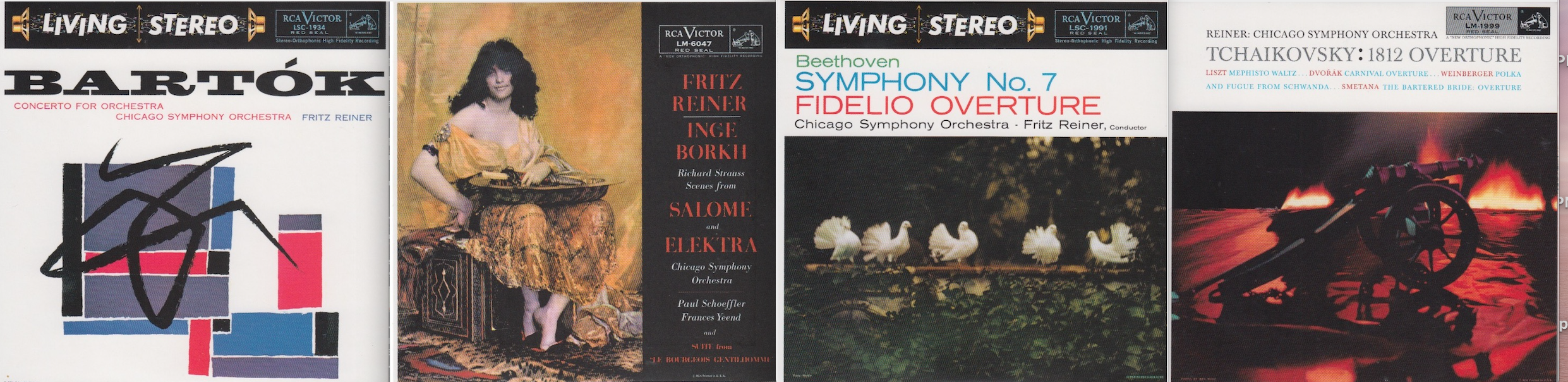

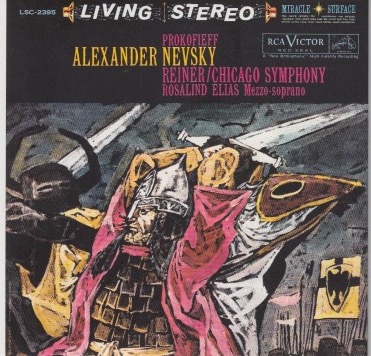

The spelling of Sergei’s name on this Frtiz Reiner Chicago Symphony Orchestra The Complete RCA Album Collection box set is starting to bug me. Nowhere else do I find his last name spelled “Prokofieff.”

It’s always “Prokofiev.”

What’s up with that?

I first noted this discrepancy on Day 22. His name on the album cover was spelled “Prokofieff.” The liner notes in the hardcover book in the box set, on the other hand, spelled it “Prokofiev.”

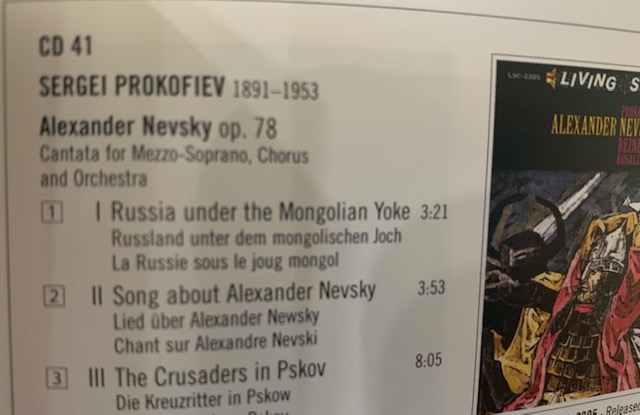

Here it is Day 41 and the man’s name is spelled in a funny way on the cover of this RCA Living Stereo album, too, even though it’s spelled correctly in the booklet.

Is this a typo? Twice, now? Or is this an Americanized spelling of Sergei Prokofiev’s name?

Ah, well. I don’t really want to spend time finding out.

I’ll just listen to this unexpectedly interesting music and do a little research as to why this opera-like score is sung in English, rather than German or Italian.

I find this music refreshing, but odd.

I’m used to hearing opera singers belt out words in the two aforementioned languages, never in English. At the same time it makes it vastly easier to understand, it seem to wring out a bit of legitimacy from the performance. Like, a serious composer would use a foreign (to me) language. A guy who composes operas in his mother’s basement in Toledo would probably use English.

In fact, hearing this sung in English reminds me of something I’d see spoofed on The Simpsons.

In searching out the English words for Alexander Nevsky, I stumbled upon a web site called Musical Musings created by whom I discovered to be an author named Alan Beggerow. He has quite a few books on Amazon that start with the phrase “Musical Musings.”

Here’s Alan’s page regarding Prokofiev’s music. Lots of great background information there, too. Check it out.

Before I delve into the objective stuff, I feel the need to ask WTF? regarding today’s Asiago bagel.

Methinks that was toasted far more than twice. The person who made it probably set the machine to “Scorched Earth.” When all is said and done, this tasted more like bagel chips than a bagel, toasted twice. Ugh.

Okay, moving right along.

The Objective Stuff

From his entry on Wikipedia,

Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev (1891-1953) was a Russian Soviet composer, pianist and conductor. As the creator of acknowledged masterpieces across numerous music genres, he is regarded as one of the major composers of the 20th century. His works include such widely heard pieces as the March from The Love for Three Oranges, the suite Lieutenant Kijé, the ballet Romeo and Juliet—from which “Dance of the Knights” is taken—and Peter and the Wolf. Of the established forms and genres in which he worked, he created – excluding juvenilia – seven completed operas, seven symphonies, eight ballets, five piano concertos, two violin concertos, a cello concerto, a symphony-concerto for cello and orchestra, and nine completed piano sonatas.

A graduate of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, Prokofiev initially made his name as an iconoclastic composer-pianist, achieving notoriety with a series of ferociously dissonant and virtuosic works for his instrument, including his first two piano concertos. In 1915, Prokofiev made a decisive break from the standard composer-pianist category with his orchestral Scythian Suite, compiled from music originally composed for a ballet commissioned by Sergei Diaghilev of the Ballets Russes. Diaghilev commissioned three further ballets from Prokofiev—Chout, Le pas d’acier and The Prodigal Son—which, at the time of their original production, all caused a sensation among both critics and colleagues. Prokofiev’s greatest interest, however, was opera, and he composed several works in that genre, including The Gambler and The Fiery Angel. Prokofiev’s one operatic success during his lifetime was The Love for Three Oranges, composed for the Chicago Opera and subsequently performed over the following decade in Europe and Russia.

From its entry on Wikipedia,

Alexander Nevsky is the score composed by Sergei Prokofiev for Sergei Eisenstein‘s 1938 film Alexander Nevsky. The subject of the film is the 13th century incursion of the knights of the Livonian Order into the territory of the Novgorod Republic, their capture of the city of Pskov, the summoning of Prince Alexander Nevsky to the defense of Rus’, and his subsequent victory over the crusaders in 1242. The majority of the score’s song texts were written by the poet Vladimir Lugovskoy.

In 1939, Prokofiev arranged the music of the film score as the cantata, Alexander Nevsky, Op. 78, for mezzo-soprano, chorus, and orchestra. It is one of the few examples (Lieutenant Kijé is another) of film music that has found a permanent place in the standard repertoire, and has also remained one of the most renowned cantatas of the 20th century.

Eisenstein, Prokofiev, and Lugovskoy later collaborated again on another historical epic, Ivan the Terrible Part 1 (1944) and Part 2 (1946, Eisenstein’s last film).

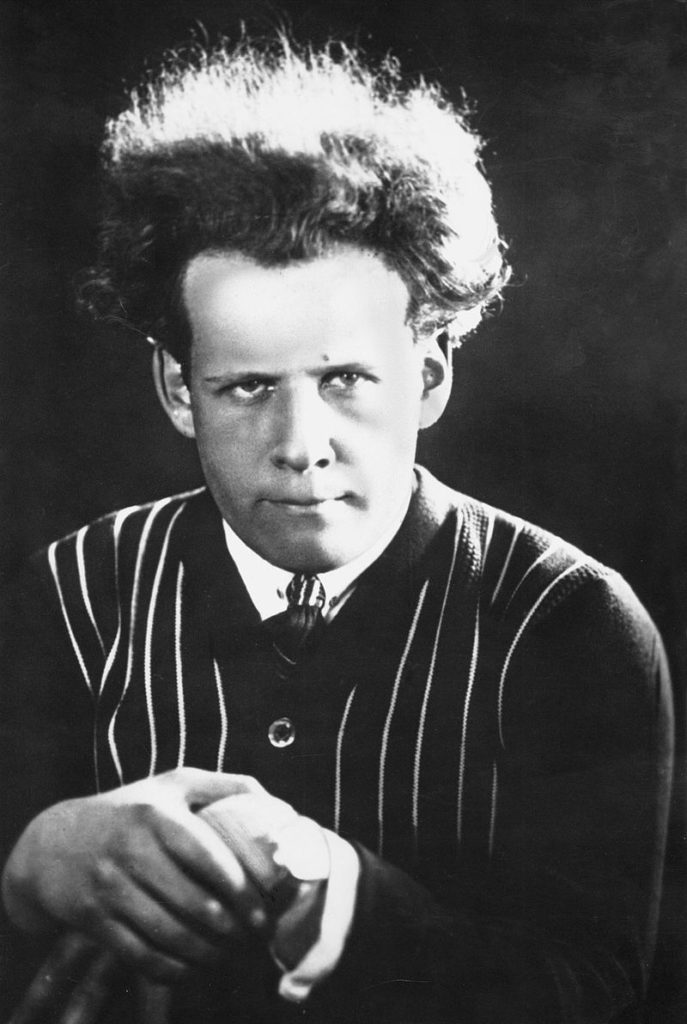

Eisenstein was an interesting character. His picture, alone, is worth the price of admission.

From his entry on Wikipedia,

Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein (1898 -1948) was a Russian film director and film theorist, a pioneer in the theory and practice of montage. He is noted in particular for his silent films Strike (1925), Battleship Potemkin (1925) and October (1928), as well as the historical epics Alexander Nevsky (1938) and Ivan the Terrible (1944, 1958). In its 2012 decennial poll, the magazine Sight & Sound named his Battleship Potemkin the 11th greatest film of all time.

The mezzo-soprano part in Alexander Nevsky was performed by Rosaline Elias. Her entry on WIkipedia tells us,

Rosalind Elias (March 13, 1930 – May 3, 2020) was an American mezzo-soprano who enjoyed a long and distinguished career at the Metropolitan Opera. She was best known for creating the role of Erika in Samuel Barber’s Vanessa in 1958.

Rosalind Elias was born in Lowell, Massachusetts, the 13th and youngest child of a Lebanese-American family. Her parents, Shelaby Namay and Salem Elias, immigrated from Beirut and her father worked as a real estate agent for some time. Elias grew up listening to Saturday broadcasts of the Metropolitan Opera while doing chores. Her father was initially opposed to her performing, but she pleaded for lessons. She received her first singing lessons in Lowell from Miss Lillian Sullivan. She studied at the New England Conservatory. She appeared with the New England Opera from 1948 to 1952. She then left for Italy to complete her vocal studies at the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia in Rome, with Luigi Ricci and Nazzareno De Angelis. As a student she sang Poppaea in L’incoronazione di Poppea and appeared with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. She continued her studies at the Berkshire Music Center at Tanglewood in Massachusetts.

Elias made her Metropolitan Opera debut as Grimgerde in Wagner’s Die Walküre, on February 23, 1954. She sang 687 performances of 54 roles there, including Bersi in Giordano’s Andrea Chénier, the title role in Bizet’s Carmen, Rosina in The Barber of Seville, Laura in La Gioconda, Suzuki in Madama Butterfly, Siebel in Faust, Nancy in Martha, Cherubino and Marcellina in The Marriage of Figaro, Dorabella in Così fan tutte, Octavian in Der Rosenkavalier, Olga in Eugene Onegin, Marina in Boris Godunov, Fenena in Nabucco, Azucena in Il trovatore, Amneris in Aida, Charlotte in Werther, and The Witch in Hansel and Gretel. She created the role of Erika in Samuel Barber’s opera Vanessa on January 15, 1958, and the role of Charmian in Antony and Cleopatra by the same composer, for the opening of new Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center, on September 16, 1966.

Elias, who had been diagnosed with congestive heart failure in 2019, was admitted to Mount Sinai West on April 30, 2020, after suffering breathing problems. She died on May 3, at age 90.

One more person of note to mention in this performance: Margaret Hillis, chorus master for the Chicago Symphony Chorus. According to her entry on Wikipedia,

Margaret Eleanor Hillis (October 1, 1921, Kokomo, Indiana – February 5, 1998, Evanston, Illinois) was an American conductor. She was the founder and first director of the Chicago Symphony Chorus.

Hillis was born in Kokomo, Indiana, in 1921. She began to study the piano at the age of five and continued with several other instruments, including woodwinds, brass, and double bass. She made her conducting debut, while still a student, as assistant conductor of her high school orchestra.

After suspending her studies during World War II to become a civilian flight instructor in Muncie, Indiana, Hillis received a bachelor of music degree in composition from Indiana University in 1947 and later studied conducting privately with Julius Herford and with Robert Shaw at the Juilliard School. She later became assistant conductor of Shaw’s Collegiate Chorale.

On September 22, 1957, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra announced that Margaret Hillis, at Music Director Fritz Reiner‘s invitation, would organize and train a symphony chorus. Auditions began two weeks later, and on March 13 and 14, 1958, the Chicago Symphony Chorus made its subscription concert debut performing Mozart’s Requiem with Bruno Walter conducting. A few weeks later, Reiner himself led the Chorus for the first time in performances of Verdi’s Requiem.

Hillis was also the first woman to conduct the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, first on a special concert in November 1957 and later on subscription concerts in December 1958, leading the orchestra and chorus in Honegger’s Christmas Cantata. Hillis captured nationwide attention[4] on October 31, 1977, when she substituted on short notice for the ailing Sir Georg Solti, conducting the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus in a performance of Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 8 in New York’s Carnegie Hall.

Under Hillis’s leadership, the Chicago Symphony Chorus performed and recorded many of the major works in the choral symphonic repertoire, gave important world premieres, appeared with visiting orchestras, and was part of many noteworthy milestones in the CSO’s history. Hillis won nine Grammy Awards from the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences for best choral performance.

Wow. That’s quite a resume.

This is why I do these musical explorations! I never would have heard of Rosaline Elias or Margaret Hillis if not for today’s recording. And both were certainly worthy of being heard of.

Today’s performance was recorded on March 7, 1959 and Orchestra Hall, Chicago. Maestro Reiner was in his 71st year. Prokofiev composed this score for Eisenstein’s film in 1938. He was about 47 years of age.

The Subjective Stuff

Recording quality: 3.5 (lots of sound, seems a bit of top end is missing)

Overall musicianship: 4

CD booklet notes: 1

CD “album cover” information: .5 (very little on front cover, nothing but abstract art on the back cover)

How does this make me feel: 4

The music in today’s performance is compelling, engaging, and mysterious. I liked it. The English singing was refreshing (because i could understand what they were saying), but it was also somewhat off-putting in that I’m not used to English-language operas, especially sung by mezzo-sopranos. But it worked here.

When the orchestra got cranking, there was a lot of sound coming into my ears. A. Lot. Of. Sound. It’s a busy score, I get it. But, wow. It was recorded close to the source and it’s a lot to take in.

Rosalind Elias appears in Track 6 (“Field of the Dead”) and, against all previous experiences with mezzo-sopranos, I found myself liking her performance. Hearing her sing in English helped, I think.

I can’t believe I’m typing these words, but I’d actually listen to this performance again.

NOTE: This is another album that needed a lot more historic background either on the album itself, or in the hardcover book’s liner notes. What is this? Who are these people? Only the bare bones basics are recorded in the liner notes. I had to discover the interesting bits myself by googling for more information.