I decided I needed a change of pace from my usual listening post of nut-squeezing, piped-in music and, thus, chose a local food store that also features a large dining area and a kiosk that serves famous caffeinated brews (hint: it’s named after “the scrupulous and steadfast first mate of the Pequod,” in Herman Melville’s novel about a great white whale).

The Blonde Roast (“it’s a pour over; will that be okay?”) and the obligatory Iced Lemon Loaf (because what goes better with over-roasted, overpriced coffee) are just what the doctor ordered. (And I didn’t even have to pay this “doctor.”)

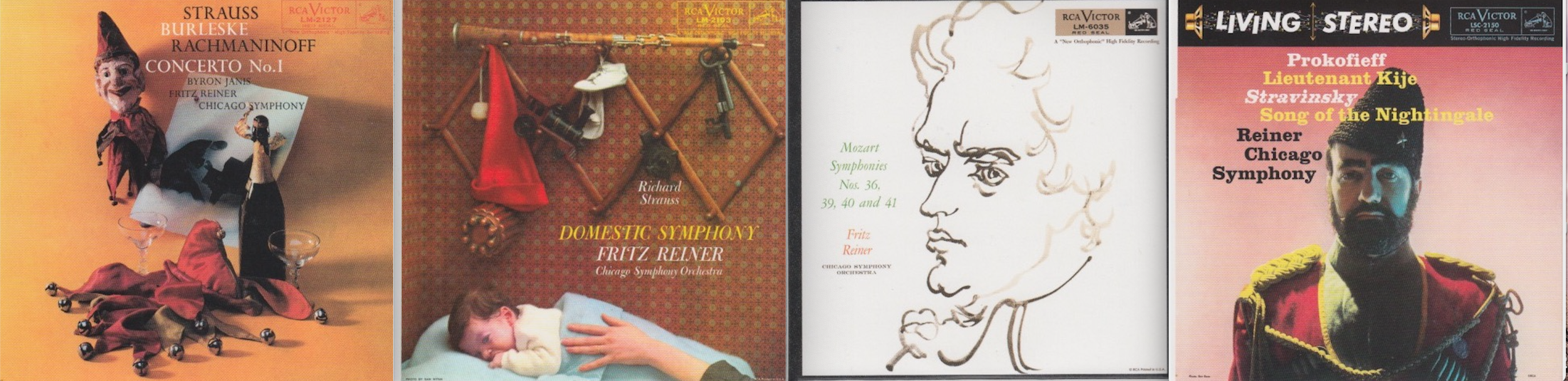

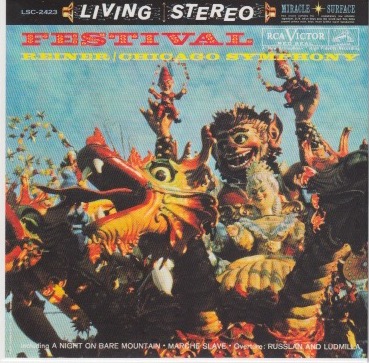

As I sit here taking in my new environment (it’s just “new” lately; I used to come here years ago on one of my other musical explorations…but I haven’t sat in one of these booths in well over a year), sipping my quickly cooling Blonde Roast, and using the black plastic fork to slice off an occasional bite of the Iced Lemon Loaf, I’m listening to today’s CD, which is a compilation of composers, three of whom (Kabalevsky, Borodin, and Glinka) I’d never heard of before.

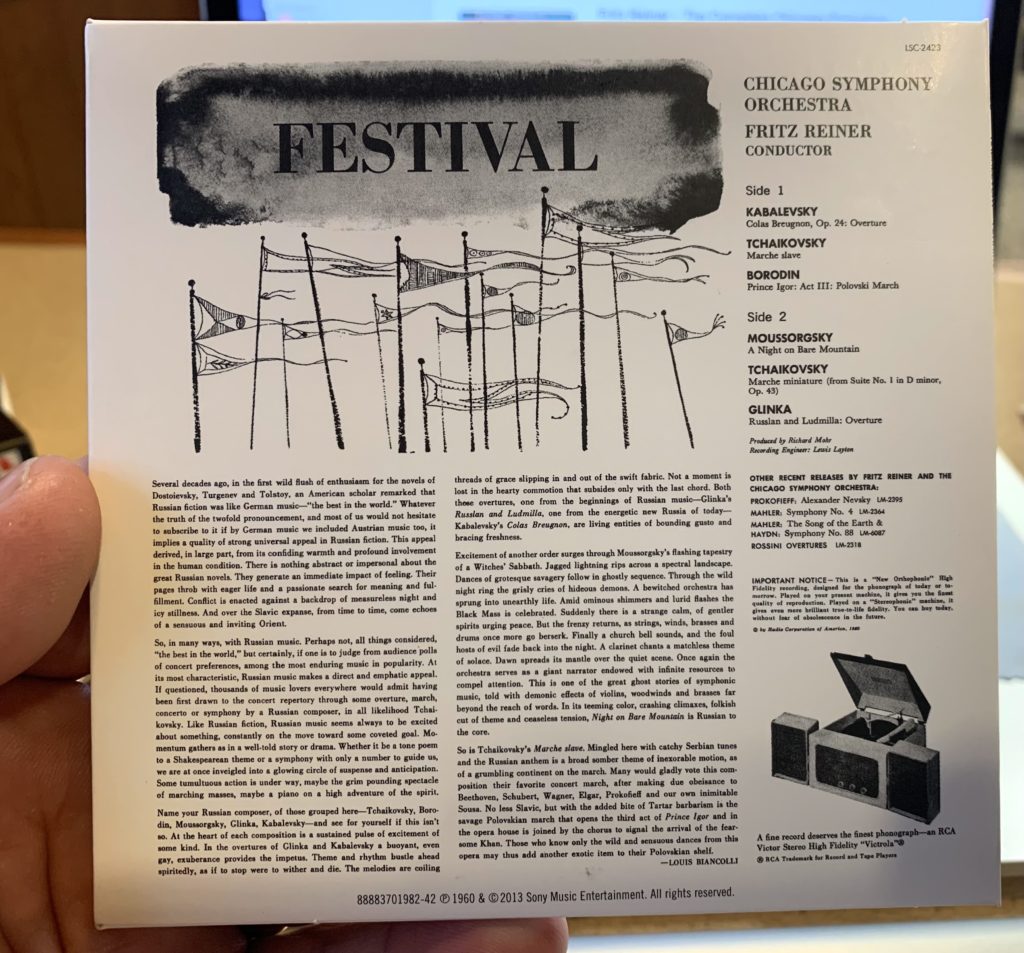

The tiny type on the back of the CD cover (written by Louis Biancolli) opens with one of the most compelling opening sentences I’ve ever read:

Several decades ago, in the first wild flush of enthusiasm for the novels of Dostoievsky [sic], Turgenev and Tolstoy, an American scholar remarked that Russian fiction was like German music – “the best in the world.” Whatever the truth of the twofold announcement, and most of us would not hesitate to subscribe to it if by German music we included American music too, it implies a quality of strong universal appeal in Russian fiction. This appeal derived, in large part, from its confiding warmth and profound involvement in the human condition. There is nothing abstract or impersonal about the great Russian novels. They generate an immediate impact of feeling. Their pages throb with eager life and a passionate search for meaning fulfillment. Conflict is enacted against a backdrop of measureless night and icy stillness. And over the Slavic expanse, from time to time, come echoes of a sensuous and inviting Orient.

I don’t know who Louis Biancolli was (is?) but that’s fine writing. I’m hooked.

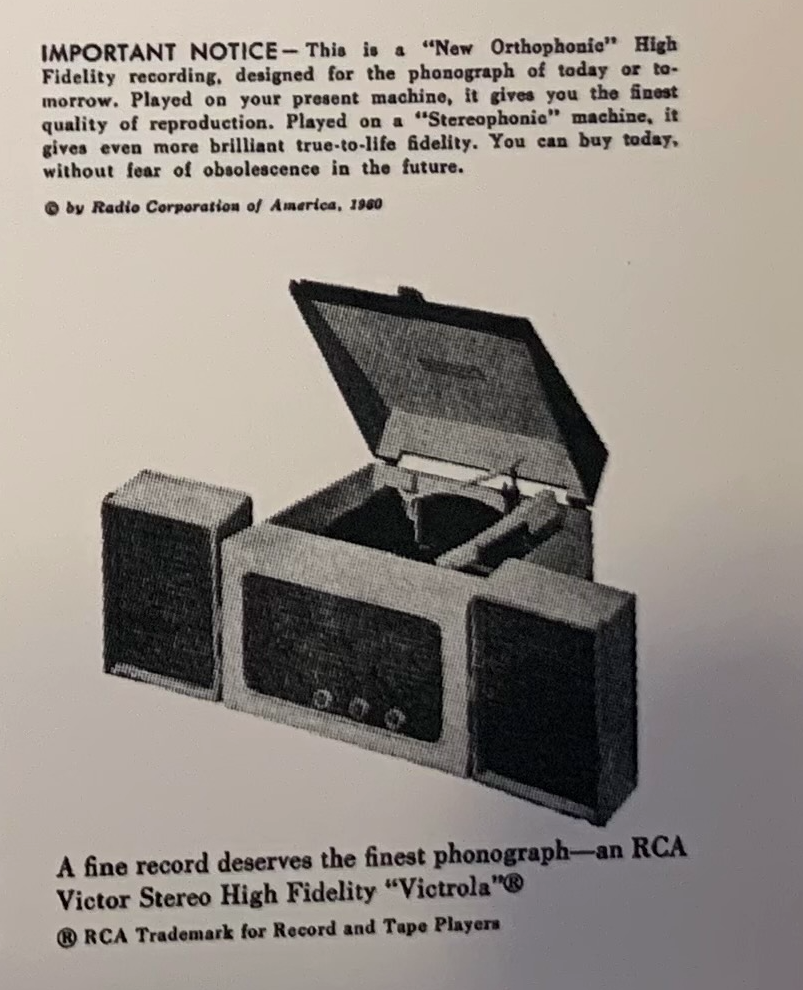

The back cover to this album is fascinating, not only because Mr. Biancolli’s copy is so compelling, but also because there’s an ad on it, in the lower right corner – for “the finest phonograph – an RCA Victor High Fidelity Victrola®”

I’d love to have one of those RCA Victor Stereo High Fidelity “Victrola” players now! I wonder what they’re worth online. I’ll check.

Also, I’ll check to see who Louis Biancolli was/is.

According to an article excerpt from the NY Times,

Louis Biancolli (1907-1992) an author and a music critic, died on Saturday at the New Milford Hospital in New Milford, Conn. He was 85 years old and lived in New Milford. He died of complications after a hip fracture, said his daughter Amy Ringwald of Albany. (Jun 16, 1992)

The Objective Stuff

From his entry on Wikipedia,

Dmitry Borisovich Kabalevsky (1904-1987) was a Soviet composer and teacher of Russian gentry descent.

He helped set up the Union of Soviet Composers in Moscow and remained one of its leading figures during his lifetime. He was a prolific composer of piano music and chamber music; many of his piano works were performed by Vladimir Horowitz. He is best known in Western Europe for his Second Symphony, the “Comedians’ Galop” from The Comedians Suite, Op. 26 and his Third Piano Concerto.

Kabalevsky was a prolific composer in many ways; he wrote symphonies, concertos, operas, ballets, chamber works, songs, theatre, film scores, pieces for children and some pieces for the proletariat. During the 1930s he wrote music for the emerging genre of films with sound (Shostakovich and Prokofiev also wrote music for this genre), some of his music became recognized in its own right. However, his biggest contribution to the world of music-making was his consistent effort to connect children to music. During 1925–6 he worked as a piano teacher in a government school and was struck by the lack of proper material for children to learn music. He set out to write easy pieces that would allow children to conquer technical difficulties and at the same time begin to form their taste. His music focused on bridging the gap between children’s technical skills and adult aesthetics. He also wrote a book on the subject, which was published in the United States in 1988 as Music and Education: A Composer Writes about Musical Education.

From his entry on Wikipedia,

Alexander Porfiryevich Borodin (1833-1887) was a Russian chemist and Romantic musical composer of Georgian ancestry. He was one of the prominent 19th-century composers known as “The Five“, a group dedicated to producing a uniquely Russian kind of Classical music. Borodin is known best for his symphonies, his two string quartets, the symphonic poem In the Steppes of Central Asia and his opera Prince Igor.

A doctor and chemist by profession and training, Borodin made important early contributions to organic chemistry. Although he is presently known better as a composer, he regarded medicine and science as his primary occupations, only practicing music and composition in his spare time or when he was ill. As a chemist, Borodin is known best for his work concerning organic synthesis, including being among the first chemists to demonstrate nucleophilic substitution, as well as being the co-discoverer of the aldol reaction. Borodin was a promoter of education in Russia and founded the School of Medicine for Women in Saint Petersburg, where he taught until 1885.

Borodin met Mily Balakirev during 1862. While under Balakirev’s tutelage in composition he began his Symphony No. 1 in E-flat major; it was first performed during 1869, with Balakirev conducting. During that same year Borodin started on his Symphony No. 2 in B minor, which was not particularly successful at its premiere during 1877 under Eduard Nápravník, but with some minor re-orchestration received a successful performance during 1879 by the Free Music School under Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s direction. During 1880 he composed the popular symphonic poem In the Steppes of Central Asia. Two years later he began composing a third symphony, but left it unfinished at his death; two movements of it were later completed and orchestrated by Alexander Glazunov.

During 1868 Borodin became distracted from initial work on the second symphony by preoccupation with the opera Prince Igor, which is considered by some to be his most significant work and one of the most important historical Russian operas. It contains the Polovtsian Dances, often performed as a stand-alone concert work forming what is probably Borodin’s best-known composition. Borodin left the opera (and a few other works) incomplete at his death.

Prince Igor was completed posthumously by Rimsky-Korsakov and Alexander Glazunov.

Now that’s fascinating. A chemist and a composer!

I had no idea such a person existed. See what these musical explorations can do for a fellow?

From his entry on Wikipedia,

Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka (1804-1857) was the first Russian composer to gain wide recognition within his own country, and is often regarded as the fountainhead of Russian classical music. Glinka’s compositions were an important influence on future Russian composers, notably the members of The Five, who took Glinka’s lead and produced a distinctive Russian style of music.

While in Berlin, Glinka had become enamored of a beautiful and talented singer, for whom he composed Six Studies for Contralto. He contrived a plan to return to her, but when his sister’s German maid turned up without the necessary paperwork to cross to the border with him, he abandoned his plan as well as his love and turned north for Saint Petersburg. There he reunited with his mother, and made the acquaintance of Maria Petrovna Ivanova. After he courted her for a brief period, the two married. The marriage was short-lived, as Maria was tactless and uninterested in his music. Although his initial fondness for her was said to have inspired the trio in the first act of opera A Life for the Tsar (1836), his naturally sweet disposition coarsened under the constant nagging of his wife and her mother. After separating, she remarried. Glinka moved in with his mother, and later with his sister, Lyudmila Shestakova.

He soon embarked on his second opera: Ruslan and Lyudmila. The plot, based on the tale by Alexander Pushkin, was concocted in 15 minutes by Konstantin Bakhturin, a poet who was drunk at the time. Consequently, the opera is a dramatic muddle, yet the quality of Glinka’s music is higher than in A Life for the Tsar. He uses a descending whole tone scale in the famous overture. This is associated with the villainous dwarf Chernomor who has abducted Lyudmila, daughter of the Prince of Kiev. There is much Italianate coloratura, and Act 3 contains several routine ballet numbers, but his great achievement in this opera lies in his use of folk melody which becomes thoroughly infused into the musical argument. Much of the borrowed folk material is oriental in origin. When it was first performed on 9 December 1842, it met with a cool reception, although it subsequently gained popularity.

I didn’t know about any of those composers!

The other two featured on this album (Tchaikovsky and Moussorgsky [sic]) I’ve already written about before. It’s a head scratcher for me that some of these names are spelled seemingly incorrectly in the liner notes. For example “Moussorgsky” seems to be “Mussorgsky” on Wikipedia and when I google the former spelling. I’m asked if I mean “Mussorgsky.” So what gives with these odd alternate spellings?

Kabelevsky’s composition on this album is the Overture to Colas Breugnon. It appears to have been completed in 1938 when Kabelevsky was 34. According to its entry on Wikipedia, “The opera is best known for its ‘rollicking’ overture.”

Borodin’s composition on this album is Prince Igor, Act III, Polovsky March. It was composed between 1869 and 1887 (it was completed posthumously) when its author was 36-54 years of age.

Apparently, Borodin died suddenly in 1887.

Glinka’s composition on this album is Russian and Ludmilla: Overture. It was composed between 1837 and 1842 when Glinka was 33-38.

Tchaikovsky has two compositions on today’s album: Marche slave, published in 1876 when Tchaikovsky was 36, and Marche miniature (Suite No. 1 in D minor), composed between 1878 and 1879 when Tchaikovsky was 38 or 39.

Mussorgsky’s contribution to today’s album is the famous A Night on Bare Mountain. (It’s more often known as A Night on Bald Mountain.) It was composed in 1867 when Mussorgsky was 28. According to its entry on Wikipedia, “it is one of the first tone poems by a Russian composer.”

All of these were recorded on the say day – March 14, 1959, in Orchestra Hall, Chicago. Maestro Reiner was in his 71st year.

The Subjective Stuff

Recording quality: 5

Overall musicianship: 5

CD booklet notes: 1

CD “album cover” information: 4 (for its well-written essay, alone)

How does this make me feel: 4.5

I found this album to be fascinating, well recorded, and immeasurably listenable. I am in agreement with Mr. Biancolli’s love of Russian music.

I was hooked from the very first track (Kabelevsky’s “rollicking” overture). But no less “rollicking,” to me, was the last track, Glinka’s Russian and Ludmilla overture.

I’d listen to this album again.

And I may look up additional recordings from these composers.

Two thumbs up!

By the way, I can’t listen to Mussorgsky’s A Night on Bald Mountain without hearing in my head the song set to a disco beat (as A Night On Disco Mountain) from the Saturday Night Fever soundtrack. I’m not sure Mussorgsky would dig it. But I think it’s a lot of fun (even though I hated the Disco era at the time).