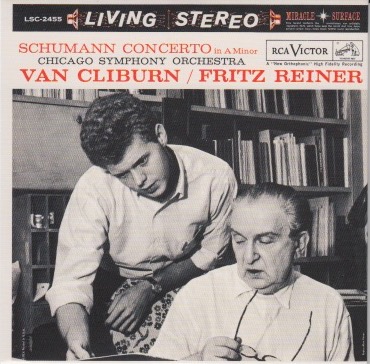

Everybody knows the name Van Cliburn (1934-2013).

I knew it decades ago, even while I was listening to The Monkees.

So when it popped up in today’s rotation, I was thrilled.

Strangely, in all of my knowing the name Van Cliburn, I don’t recall ever hearing him play.

Today’s the day I will rectify that tragic oversight.

From his entry on Wikipedia,

Harvey Lavan “Van” Cliburn Jr. (1934-2013) was an American pianist who, at the age of 23, achieved worldwide recognition when he won the inaugural International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow in 1958 (during the Cold War). Cliburn’s mother, a piano teacher and an accomplished pianist in her own right, discovered him playing at age three, mimicking one of her students and arranged for him to start taking lessons. Cliburn developed a rich, round tone and a singing-voice-like phrasing, having been taught from the start to sing each piece.

Cliburn toured domestically and overseas. He played for royalty, heads of state, and every US president from Harry S. Truman to Barack Obama.

Cliburn was born in Shreveport, Louisiana, the son of Rildia Bee (née O’Bryan) and Harvey Lavan Cliburn Sr. When he was three, he began taking piano lessons from his mother, who had studied under Arthur Friedheim, a pupil of Franz Liszt. When Cliburn was six, his father, who worked in the oil industry, moved the family to Kilgore, Texas.

At 12, Cliburn won a statewide piano competition, which led to his debut with the Houston Symphony Orchestra. He entered the Juilliard School in New York City at 17 and studied under Rosina Lhévinne, who trained him in the tradition of the great Russian romantics. In 1952, Cliburn won the International Chopin Competition at the Kosciuszko Foundation in New York City. At 20, Cliburn won the Leventritt Award and made his debut at Carnegie Hall.

The first International Tchaikovsky Competition in 1958 was an event designed to demonstrate Soviet cultural superiority during the Cold War, after the USSR’s technological victory with the Sputnik launch in October 1957. Cliburn’s performance at the competition finale of Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1 and Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 3 on April 13 earned him a standing ovation lasting eight minutes. After the ovation, Van Cliburn made a brief speech in Russian and then resumed his seat at the piano and began to play—to the surprise and delight of the Russian musicians visible behind him in the film made of his part in the competition—his own piano arrangement of the much-beloved song “Moscow Nights,” which, as the response shows, further endeared him to the Russians.

Cliburn received the Kennedy Center Honors on December 2, 2001. He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom on July 23, 2003 by President George W. Bush, and, on September 20, 2004, the Russian Order of Friendship, the highest civilian awards of the two countries. He was also awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award the same year and played at a surprise 50th birthday party for United States Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice. He was a member of the Alpha Chi chapter of Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia, and was awarded the fraternity’s Charles E. Lutton Man of Music Award in 1962. He was presented a 2010 National Medal of Arts by President Barack Obama on March 2, 2011.

Cliburn’s 1958 piano performance in Moscow, when he won the prestigious Tchaikovsky International Piano Competition, has been added to the National Recording Registry in the Library of Congress for long-term preservation

From its entry on Wikipedia,

The Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 54, by the German Romantic composer Robert Schumann was completed in 1845 and is the composer’s only piano concerto. The complete work was premiered in Dresden on 4 December 1845. It is one of the most widely performed and recorded piano concertos from the Romantic period.

Schumann had worked on several piano concertos earlier. He began one in E-flat major in 1828, from 1829–31 he worked on one in F major, and in 1839, he wrote one movement of a concerto in D minor. None of these works were completed.

Already on 10 January 1833, Schumann first expressed the idea of writing a Piano Concerto in A minor. In a letter to his future father-in-law, Friedrich Wieck, he wrote: “I think the piano concerto must be in C major or in A minor.”[1] From 17–20 May 1841, Schumann wrote a fantasy for piano and orchestra, his Phantasie in A minor.[2] Schumann tried unsuccessfully to sell this one-movement piece to publishers. In August 1841 and January 1843 Schumann revised the piece, but was unsuccessful. His wife Clara, an accomplished pianist, then urged him to expand it into a full piano concerto. In 1845 he added the Intermezzo and Allegro vivace to complete the work. It remained the only piano concerto that Schumann finished.

From his entry on Wikipedia,

Robert Schumann (1810-1856) was a German composer, pianist, and influential music critic. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest composers of the Romantic era. Schumann left the study of law, intending to pursue a career as a virtuoso pianist. His teacher, Friedrich Wieck, a German pianist, had assured him that he could become the finest pianist in Europe, but a hand injury ended this dream. Schumann then focused his musical energies on composing.

In 1840, Schumann married Clara Wieck, after a long and acrimonious legal battle with her father, Friedrich, who opposed the marriage. A lifelong partnership in music began, as Clara herself was an established pianist and music prodigy. Clara and Robert also maintained a close relationship with German composer Johannes Brahms.

Until 1840, Schumann wrote exclusively for the piano. Later, he composed piano and orchestral works, and many Lieder (songs for voice and piano). He composed four symphonies, one opera, and other orchestral, choral, and chamber works. His best-known works include Carnaval, Symphonic Studies, Kinderszenen, Kreisleriana, and the Fantasie in C. Schumann was known for infusing his music with characters through motifs, as well as references to works of literature. These characters bled into his editorial writing in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik (New Journal for Music), a Leipzig-based publication that he co-founded.

Schumann suffered from a mental disorder that first manifested in 1833 as a severe melancholic depressive episode—which recurred several times alternating with phases of “exaltation” and increasingly also delusional ideas of being poisoned or threatened with metallic items. What is now thought to have been a combination of bipolar disorder and perhaps mercury poisoning led to “manic” and “depressive” periods in Schumann’s compositional productivity. After a suicide attempt in 1854, Schumann was admitted at his own request to a mental asylum in Endenich near Bonn. Diagnosed with psychotic melancholia, he died of pneumonia two years later at the age of 46, without recovering from his mental illness.

Yikes. Another tragic end for a composer.

Schumann completed his Concerto in 1845. He was 35. This performance was recorded on April 16, 1960. Van Cliburn was 26. Maestro Reiner was in his 72nd year.

The Subjective Stuff

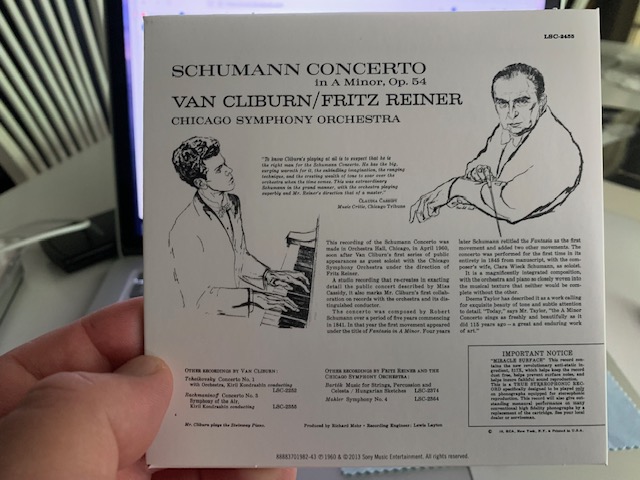

Recording quality: 5

Overall musicianship: 5

CD booklet notes: 1

CD “album cover” information: 3 (not much info here)

How does this make me feel: 5

Brilliant.

Brilliant from start to finish.

The piano wasn’t recorded so hot that it jarred my ear drums (as it was with the Tchaikovsky piano composition I heard the other day). The piano was organically interwoven with the orchestral music. But it stood out because Van Cliburn was a gifted, dynamic, highly skilled artist.

This was magical music, from start to finish, the kind of music for which I do explorations.

I will listen to this CD many times because it’s gorgeous.