Today brings another musical discovery for me.

I’d never heard of Ottorino Respighi (1879-1936) before this morning.

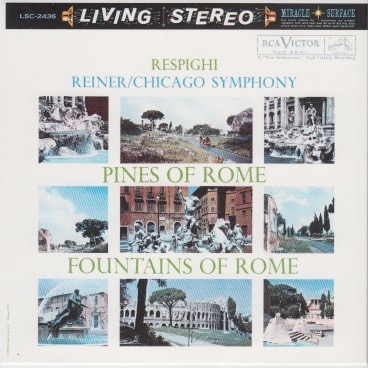

Therefore, I’d never heard of these two compositions – Pines of Rome and Fountains of Rome – either.

But I’m hearing one of them (Pines of Rome) as I type these words. And it’s not bad. Not generally, as they say, my cup of tea. But I’ve been known to drink a lot of varieties of tea in my day. So one more cup, albeit slightly different, isn’t going to push me over the edge

The Objective Stuff

From his entry on Wikipedia,

Ottorino Respighi (1879-1936) was an Italian composer, violinist, teacher, and musicologist who was one of the leading Italian composers of the early 20th century. His compositions range over operas, ballets, orchestral suites, choral songs, and chamber music, and include transcriptions of pieces from Italian composers of the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries and works of Bach and Rachmaninoff. Among his best known and most performed works are his three Roman tone poems, which brought him international fame: Fountains of Rome (1916), Pines of Rome (1924), and Roman Festivals (1928). All three demonstrate Respighi’s use of rich orchestral colours.

Born and raised in Bologna, Respighi studied violin, viola, and composition at the Liceo Musicale di Bologna. He also worked in Saint Petersburg and studied briefly with Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. In 1913, Respighi moved to Rome, where he became professor of composition at the Liceo Musicale di Santa Cecilia. He left the school to dedicate his time fully to composing.

While composing his opera Lucrezia in early 1936, Respighi was diagnosed with bacterial endocarditis. He died four months later aged 56. His wife Elsa Respighi outlived him for almost 60 years, championing her late husband’s works and legacy until her death in 1996.

Great. Another sad ending to a promising life, hardly even lived.

If it wasn’t for bad luck, some of these guys would have no luck at all.

But, at least they leave behind words that can be studied and appreciated for decades, perhaps centuries, to come.

From its entry on Wikipedia,

Pines of Rome (Italian title: Pini di Roma) is a four-movement symphonic poem for orchestra completed in 1924 by the Italian composer Ottorino Respighi. The piece, which depicts pine trees in four locations in Rome at different times of the day, is the second of Respighi’s trilogy of tone poems based on the city, along with Fountains of Rome (1917) and Roman Festivals (1928). It premiered on 14 December 1924 at the Augusteo Theatre in Rome with Bernardino Molinari conducting the Augusteo Orchestra, now known as the Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia.

Pines of Rome is the third tone poem for orchestra in Respighi’s collection of works. Similar to that of a symphony, the piece is a suite of four movements, each depicting pine trees located in different areas in the city of Rome at different times of the day. Respighi wrote a short description of each movement.

Pines of Rome is easily the most prolifically recorded of all Respighi’s works, frequently released as part of his trilogy of Roman-inspired works, but just as often not. As of 2018, more than 100 recordings of the piece are currently available on physical media alone.

Respighi was 45 when he completed the Pines of Rome.

From its entry on Wikipedia,

Fountains of Rome (Italian: Fontane di Roma) is a symphonic poem written by the Italian composer Ottorino Respighi in 1916 and first published in 1918. It was his first great success as a composer and is his best known work. He wrote as sequels two other works: Pines of Rome (1924) and Roman Festivals (1928).

Each of the four movements depicts one of Rome’s fountains at a different time of the day.

Its premiere was held on March 11, 1917 at the Teatro Augusteo in Rome, under the direction of Antonio Guarnieri.

Arturo Toscanini originally planned to conduct the work in 1916, but the Italian composer refused to appear for the performance after a disagreement over his having included some of Wagner’s music on a program played during World War I. Consequently, it did not premiere until March 11, 1917, at the Teatro Augusteo in Rome, with Antonio Guarnieri as conductor. Although the premiere was unsuccessful, Toscanini finally conducted the work in Milan in 1918 with tremendous success. It “was acclaimed [as] one of the loveliest of symphonic writings”.

The piece was first performed in the United States on February 13, 1919. Toscanini recorded the music with the NBC Symphony Orchestra in Carnegie Hall in 1951; the high fidelity monaural recording was issued on LP and then digitally remastered for release on CD by RCA Victor. The work has since become one of the most eminent examples of the symphonic poem.

Respighi was 37 when he completed Fountains of Rome.

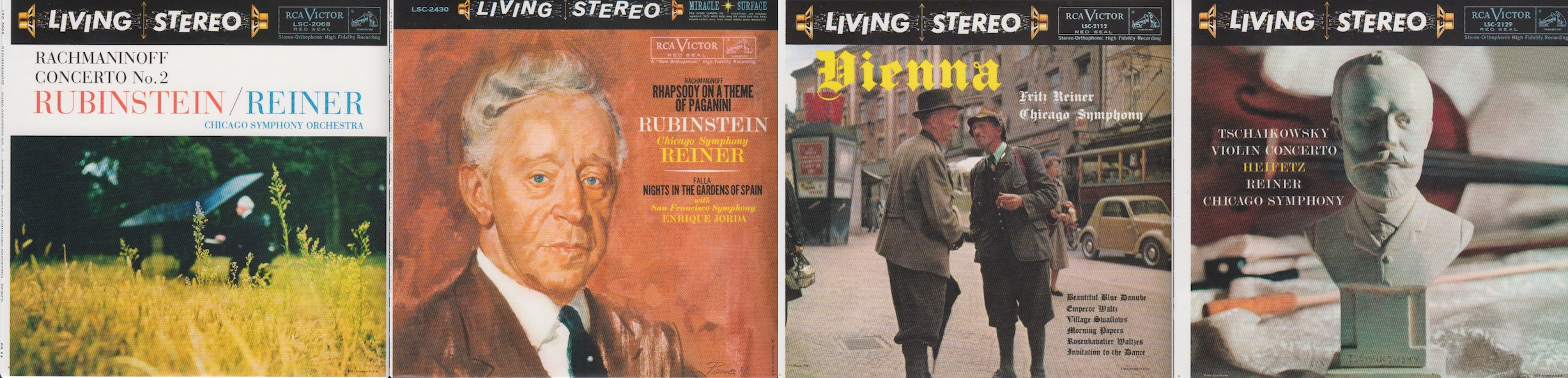

Both of these performances were recorded on October 24, 1959. Maestro Reiner was in his 71st year.

The Subjective Stuff

Recording quality: 5

Overall musicianship: 5

CD booklet notes: 1

CD “album cover” information: 3 (not much info here)

How does this make me feel: 4.5

I love stuff like this.

Respighi looked around at things in Rome (pine trees, fountains) and did what few others could have, and – as far as I know – no one else did: lauded immortalized them in music.

If Ottorino Respighi had been a writer, he probably would have done the same thing in a novel, or a series of novellas. After all, attention to detail of seemingly mundane things made Nicholson Baker a famous author. His novel The Mezzanine, according to its entry on Wikipedia:

The Mezzanine (1988) is the first novel by American writer Nicholson Baker. It narrates what goes through a man’s mind during a modern lunch break.

On the surface, the novel deals with a man’s lunchtime trip up an escalator in the mezzanine of the office building where he works (a building based on Baker’s recollections of Rochester’s Midtown Plaza). The substance of the novel, however, is taken up with the thoughts that run through a person’s mind in any given few moments, and the ideas that might result if he or she were given the time to think these thoughts through to their conclusions. The Mezzanine tells this story through the extensive use of footnotes—some of them comprising the bulk of the page—as the narrator travels through his own mind and past. The footnotes are quite detailed and sometimes diverge into multiple levels of abstraction. Near the end of the book, there is a multi-page footnote on the subject of footnotes themselves.

So, Baker used words. Respighi used musical notes. Essentially, they both captured a moment in time – one (Baker) a matter of pure imagination (The Mezzanine takes place in the protagonist’s head) and conjecture, the other (Respighi) a matter of pure observation and romanticizing.

Some of these two compositions were stunning. Totally engrossing.

An occasional part (the ending to the first movement of Pines of Rome, for example) gave me a headache.

A few passages (the opening to the fourth movement of Fountains, for example), were sublime. Gorgeous. Also, the third movement to Pines was so lush and beautiful that I could almost see the trees swaying.

These performances were very well recorded.

I’ll definitely listen to this recording again.

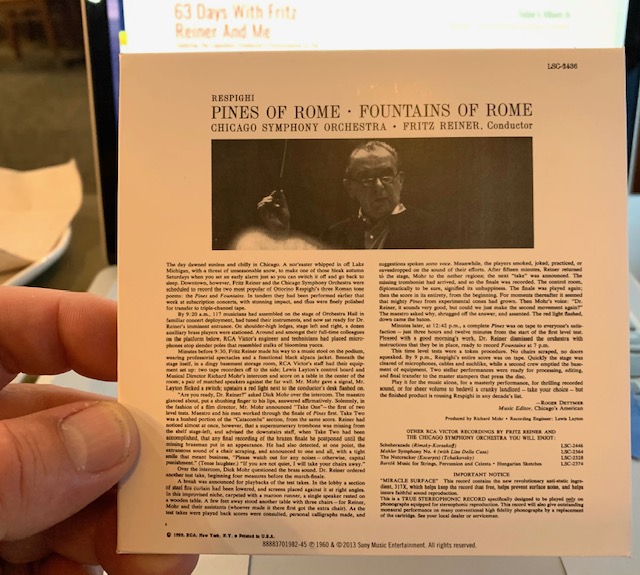

Oh, by the way, the essay on the back of the album cover is interesting in that I read it after I wrote the above about Nicholson Baker’s novel The Mezzanine – and then I noticed similarities regarding it and what I wrote.

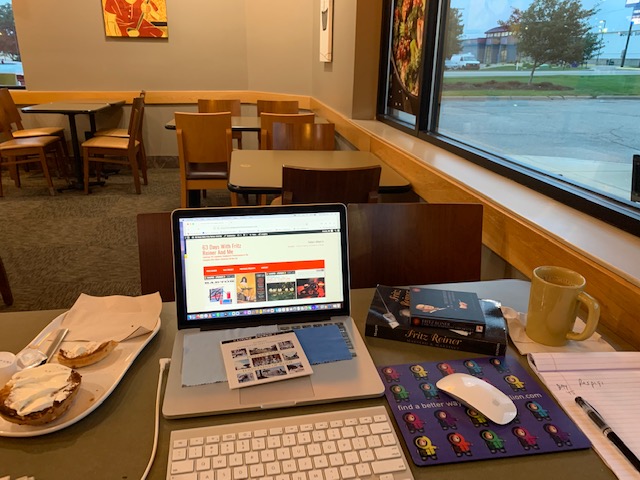

Composed by Roger Dettmer (music editor, Chicago’s American), it is not so much a description of Respighi, Reiner, or anything objective. It is more of an observation – whether gleaned first hand or not, I don’t know – of the day’s recording process. Here are two brief excerpts (to read it all, you’ll have to buy the album yourself),

By 9:20 a.m., 117 musicians had assembled on the stage of Orchestra Hall in familiar concert deployment, had tuned their instruments, and now sat ready for Dr. Reiner’s imminent entrance. On shoulder-high ledges, stage left and right, a dozen military brass players were stationed. Around and amongst their full-time colleagues on the platform below, RCA Victor’s engineer and technicians had placed microphones atop slender poles that resembled stalks of bloomless yucca.

By 9 p.m., Respighi’s entire score was on tape. Quickly the stage was cleared of microphones, cables and suchlike, while a second crew emptied the basement of equipment. Two stellar performances were ready for processing, editing, and final transfer to the master stampers that press the disc.

A 12-hour day of recording! Imagine how tired the musicians must have been.

Incidentally, Dettmer wrote a lengthy obituary for Fritz Reiner when he passed in 1963. Read it here.

If you google “Roger Dettmer, music critic” you’ll find all sorts of articles, many about the late Fritz Reiner.