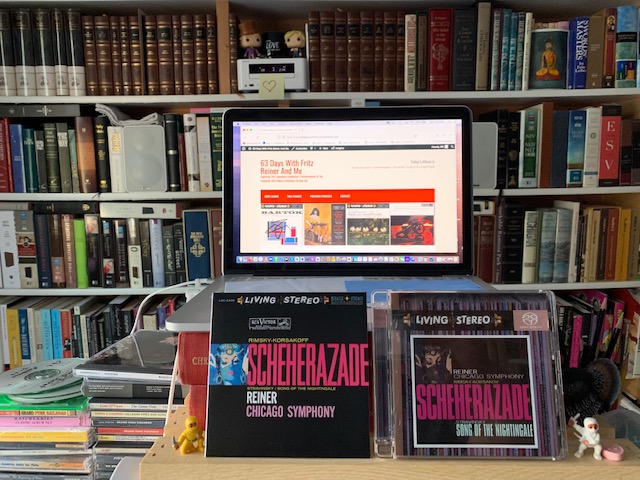

This was the first Fritz Reiner /CSO CD I ever purchased, and it’s still my favorite.

When I’m not listening to an audio book in the car – my current favorite is the Longmire series, consisting of 17 novels written by Craig Johnson, narrated by George Guidall – I’m listening to our local Classical radio station (WBLV and WBLU-FM, known collectively as Blue Lake Public Radio).

It was there, on WBLV, that I first heard Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade performed by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Fritz Reiner.

What sold me on this recording – which I immediately sought out online and purchased the next day – was the haunting quality of the music and, most of all, Sidney Harth’s gorgeous violin solo. I was spellbound, absolutely captivated listening to Harth.

For my money, there’s no finer RCA Living Stereo recording featuring the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Fritz Reiner. Nothing I’ve listened to so far (all previous 45 albums in this box set) even comes close. This is the pinnacle, the gold standard. It is perfect in every way.

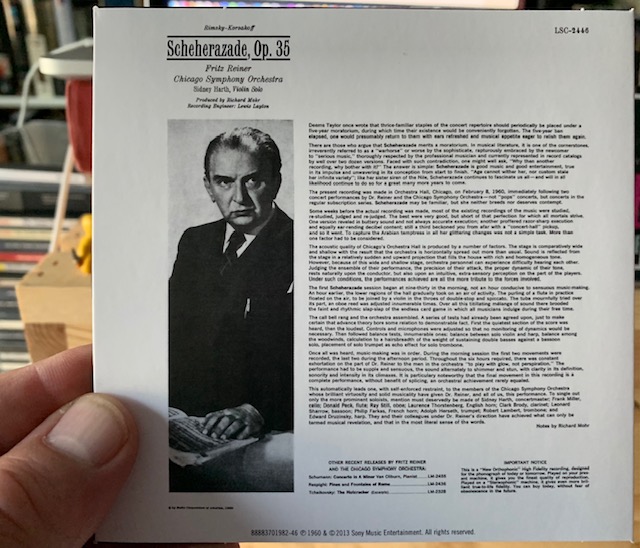

The teeny tiny notes on the back of the album cover – which can only be seen under a magnifying glass or by taking a high-res picture with one’s iPhone, e-mailing it to oneself, and then using the magnifying glass tool on one’s laptop to increase the point size – reveal some of what went on the day of the recording.

The musicians started at 9:30 a.m. on February 8th, 1960.

It was a Monday. (I know; I looked it up.)

And it was likely freezing outside. (I don’t have to look that up. I know what the Midwest feels like in February.)

Inside, the musicians had to contend with Maestro Fritz Reiner who was – by all accounts – a martinet, a taskmaster, a short-tempered perfectionist with impossibly high standards.

It must have been just shy of hell on earth.

But, in the case of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade, in was a hell that stole from heaven some of the greatest music ever recorded.

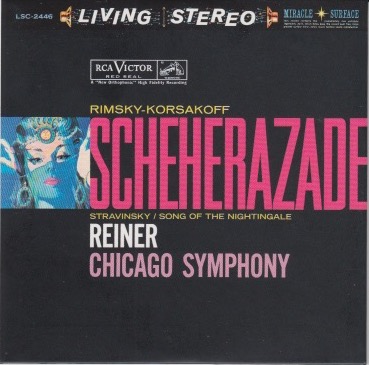

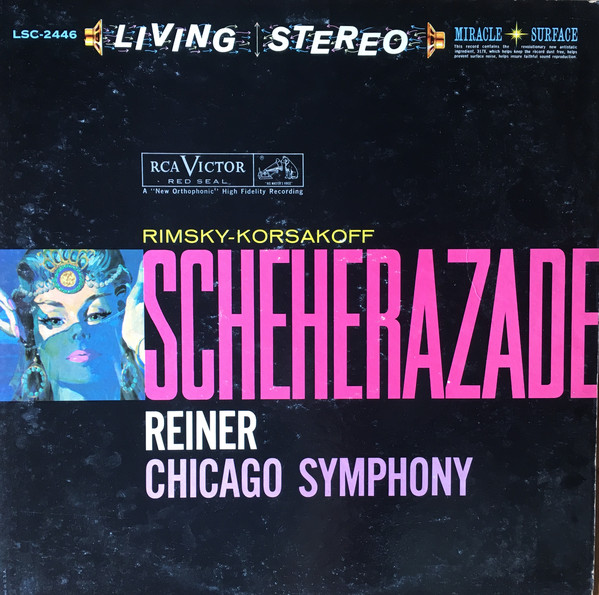

What I want to know, though, is why there are weird alternate spellings for some of the composer’s names on these Fritz Reiner box set albums. In this case, it’s the spelling of “Rimsky-Korsakoff” instead of (even on reissue CDs of the same album) “Rimsky-Korsakov”?

Who green lighted “Korsakoff”? And why?

Another “Why?” question: Why does the cover list Stravinsky’s Song of the Nightingale, but that performance is not on this album?

There is one on the SACD Audio version of this album, however. But there isn’t on the album in the Fritz Reiner box set.

The hardcover book that came with the box set doesn’t list Stravinsky’s Song of the Nightingale, either. However, the photo of the cover of the album pictured in the book does.

Was it always that way – a composition listed on the cover of the original album that was never actually on the album?

Or did somebody use the cover of the SACD Audio version – which not only lists Stravinsky’s Song of the Nightingale on the cover, but also includes it on the CD – instead of the original cover of this album?

Mystery solved.

I did a little Internet research and found the original album (LP) cover as it was released in 1960.

No mention of Stravinsky’s Song of the Nightingale.

Therefore, whomever put together the Fritz Reiner box set used the incorrect image for the cover of the Rimsky-Korsakov Scheherazade album.

He/she used the cover of the SACD Audio edition, which corrects the spelling of Rimsky-Korsakov’s name (from Rimsky-Korsakoff) but lists the addition of Stravinsky’s Song of the Nightingale, which wasn’t included in the original album (LP) release in 1960.

That’s pretty sloppy work on someone’s part, especially for a box set this important to the world of Classical music.

The Objective Stuff

According to his entry on Wikipedia,

Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908) was a Russian composer, and a member of the group of composers known as The Five. He was a master of orchestration. His best-known orchestral compositions—Capriccio Espagnol, the Russian Easter Festival Overture, and the symphonic suite Scheherazade—are staples of the classical music repertoire, along with suites and excerpts from some of his 15 operas. Scheherazade is an example of his frequent use of fairy-tale and folk subjects.

Rimsky-Korsakov believed in developing a nationalistic style of classical music, as did his fellow composer Mily Balakirev and the critic Vladimir Stasov. This style employed Russian folk song and lore along with exotic harmonic, melodic and rhythmic elements in a practice known as musical orientalism, and eschewed traditional Western compositional methods. Rimsky-Korsakov appreciated Western musical techniques after he became a professor of musical composition, harmony, and orchestration at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory in 1871. He undertook a rigorous three-year program of self-education and became a master of Western methods, incorporating them alongside the influences of Mikhail Glinka and fellow members of The Five. Rimsky-Korsakov’s techniques of composition and orchestration were further enriched by his exposure to the works of Richard Wagner.

For much of his life, Rimsky-Korsakov combined his composition and teaching with a career in the Russian military—first as an officer in the Imperial Russian Navy, then as the civilian Inspector of Naval Bands. He wrote that he developed a passion for the ocean in childhood from reading books and hearing of his older brother’s exploits in the navy. This love of the sea may have influenced him to write two of his best-known orchestral works, the musical tableau Sadko (not to be confused with his later opera of the same name) and Scheherazade.

Beginning around 1890, Rimsky-Korsakov suffered from angina. While this ailment initially wore him down gradually, the stresses concurrent with the 1905 Revolution and its aftermath greatly accelerated its progress. After December 1907, his illness became severe, and he could not work. In 1908, he died at his Lubensk estate near Luga (modern day Plyussky District of Pskov Oblast), and was interred in Tikhvin Cemetery at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery in Saint Petersburg, next to Borodin, Glinka, Mussorgsky and Stasov.

From its entry on Wikipedia,

Scheherazade, also commonly Sheherazade, Op. 35, is a symphonic suite composed by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov in 1888 and based on One Thousand and One Nights (also known as The Arabian Nights).

This orchestral work combines two features typical of Russian music in general and of Rimsky-Korsakov in particular: dazzling, colorful orchestration and an interest in the East, which figured greatly in the history of Imperial Russia, as well as orientalism in general. The name “Scheherazade” refers to the main character Scheherazade of the One Thousand and One Nights. It is considered Rimsky-Korsakov’s most popular work.

Rimsky-Korsakov was 44 when he composed this piece of music. (Incidentally, it was composed the same year Fritz Reiner was born.) Maestro Reiner was in his 72nd year when this was recorded in Orchestra Hall.

From an article on the Experience CSO site (an interview with cellist David Sanders),

RIMSKY-KORSAKOV Sheherazade, Op. 35

Recorded in Orchestra Hall in 1960 for RCA

Fritz Reiner conductor

Sidney Harth violin

“While at Northwestern University, a number of my friends were wind and brass players whose teachers were Chicago Symphony Orchestra members. We would often listen to CSO recordings over and over, to hear how these wonderful musicians would turn a phrase and how the conductors would structure the music. In those years, probably the two recordings I listened to the most were Rimsky-Korsakov’s Sheherazade conducted by Fritz Reiner and recorded in 1960, and Frank Martin’s Concerto for Seven Wind Instruments, Timpani, Percussion, and String Orchestra conducted by Jean Martinon and recorded in 1966. The playing in both of these was breathtaking, and the record jacket informed us that the last movement of Sheherazade had been recorded in one take. The beauty of Frank Miller’s cello solos, Sidney Harth’s violin solos, and Ray Still’s oboe solos to this day still bring chills to my spine. The playing of the concerto soloists in the Martin, including a newly appointed Dale Clevenger, was awe inspiring.”

The Subjective Stuff

Recording quality: 5

Overall musicianship: 5

CD booklet notes: 1 (incorrect album cover image there, too)

CD “album cover” information: 1 (3 for the fun story in tiny type on back, -2 for the incorrect image on the front)

How does this make me feel: 10 (peerless)

I agree with Mr. Sanders.

This is awe-inspiring music, indeed.

If the fourth movement (Festival at Baghdad, the Sea, Shipwreck) of this exquisite piece of music doesn’t cause you to pick your jaw up off the floor, then you’re just not human.

Period.

The violin solo, alone, in that movement is so beautiful it hurts.

But every note of this entire performance is captivating. If I could award this a “10,” I would.

Hell, I can award this a “10.” It’s my blog. I can rate things any way I want.

There. On my scale of 1-5, I just gave this a “10.”

Take that self-imposed, subjective rating system!

This is one of the most gorgeous pieces of music I’ve ever heard in my life. And it was captured flawlessly by the engineers, and performed with more magic and verve than I’ve yet heard from the CSO and Maestro Reiner.

If you only buy one Classical record, make it this one.