It’s funny how a person associated with someone negative can taint the person.

Sort of like the old saying, “one bad apple can spoil the whole bunch.”

When it comes to Richard Wagner (1813-1883), his antisemitism and, later, musical appropriation by Hitler sort of taints everything for me.

Whereas some of these composers made me like their music more because of their tragic end, or their challenging lives, or even their incredible creativity, Wagner doesn’t inspire such lofty thoughts from me.

For one thing, his music bores me to tears.

For another, I’m always appalled by antisemitism, for it – like any racism/bigotry – is inexplicable. It has no logical basis in reality. It’s an irrational fear or hatred for others that (in my experience watching others who have fallen prey to it) colors everything in their lives. Their thoughts become twisted and their actions become erratic.

In short, people become what they fixate upon. If they hate others, they become hateful. If they are afraid of others, they become fearful.

So, I wonder what Richard Wagner’s life was like, and how much of his antisemitism spilled over into the music he created.

Or does it really matter? Is music neither good nor bad? Or does it, in some fashion, wipe out whatever faults were inherent in its creator?

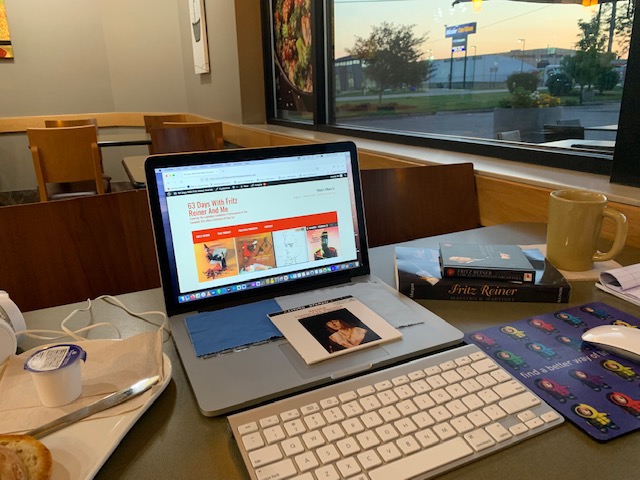

As I sit here this morning with my Asiago bagel (toasted twice!) plus a Light Roast coffee, looking out the window at a sky that hasn’t yet seen the sun rise, listening to Wagner’s music, I have plenty of time to ponder the imponderables of life, and listen to this uninspiring music.

The Objective Stuff

From his entry on Wikipedia,

Wilhelm Richard Wagner (1813-1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, “music dramas”). Unlike most opera composers, Wagner wrote both the libretto and the music for each of his stage works. Initially establishing his reputation as a composer of works in the romantic vein of Carl Maria von Weber and Giacomo Meyerbeer, Wagner revolutionised opera through his concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk (“total work of art”), by which he sought to synthesise the poetic, visual, musical and dramatic arts, with music subsidiary to drama. He described this vision in a series of essays published between 1849 and 1852. Wagner realised these ideas most fully in the first half of the four-opera cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung).

His compositions, particularly those of his later period, are notable for their complex textures, rich harmonies and orchestration, and the elaborate use of leitmotifs—musical phrases associated with individual characters, places, ideas, or plot elements. His advances in musical language, such as extreme chromaticism and quickly shifting tonal centres, greatly influenced the development of classical music. His Tristan und Isolde is sometimes described as marking the start of modern music.

Wagner had his own opera house built, the Bayreuth Festspielhaus, which embodied many novel design features. The Ring and Parsifal were premiered here and his most important stage works continue to be performed at the annual Bayreuth Festival, run by his descendants. His thoughts on the relative contributions of music and drama in opera were to change again, and he reintroduced some traditional forms into his last few stage works, including Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (The Mastersingers of Nuremberg).

Until his final years, Wagner’s life was characterised by political exile, turbulent love affairs, poverty and repeated flight from his creditors. His controversial writings on music, drama and politics have attracted extensive comment – particularly, since the late 20th century, where they express antisemitic sentiments. The effect of his ideas can be traced in many of the arts throughout the 20th century; his influence spread beyond composition into conducting, philosophy, literature, the visual arts and theatre.

One of the things I enjoy about researching these composers is learning how influential they were, how large a role they played on composers and their music who came after them.

Wagner appears to have been highly influential.

So far, I’m not swayed by that fact.

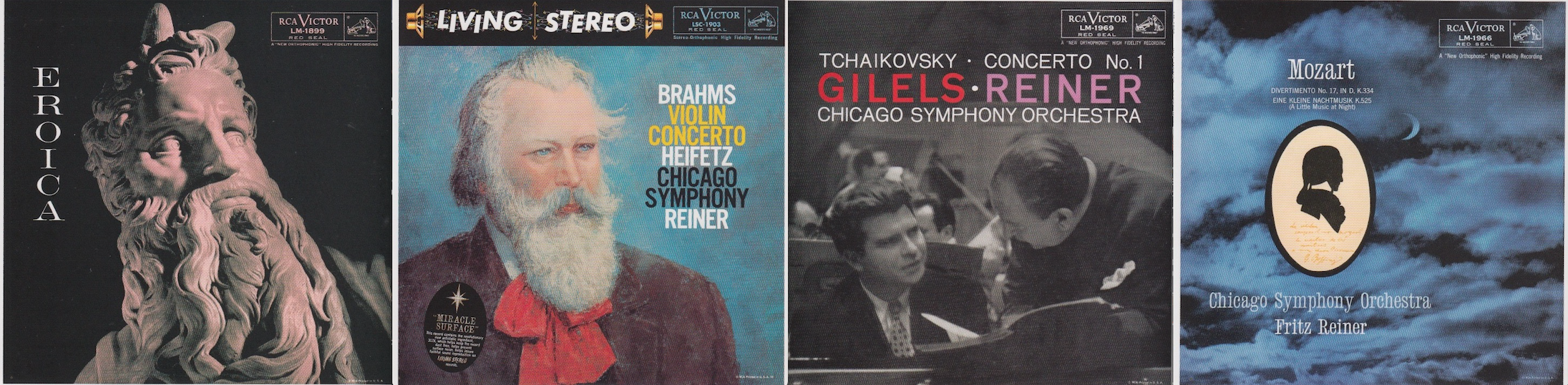

From its entry on Wikipedia,

Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (“The Master-Singers of Nuremberg”), WWV 96, is a music drama (or opera) in three acts, written and composed by Richard Wagner. It is among the longest operas commonly performed, usually taking around four and a half hours. It was first performed at the National Theatre Munich, today the home of the Bavarian State Opera, in Munich, on 21 June 1868. The conductor at the premiere was Hans von Bülow.

The story is set in Nuremberg in the mid-16th century. At the time, Nuremberg was a free imperial city and one of the centers of the Renaissance in Northern Europe. The story revolves around the city’s guild of Meistersinger (Master Singers), an association of amateur poets and musicians who were primarily master craftsmen of various trades. The master singers had developed a craftsmanlike approach to music-making, with an intricate system of rules for composing and performing songs. The work draws much of its atmosphere from its depiction of the Nuremberg of the era and the traditions of the master-singer guild. One of the main characters, the cobbler-poet Hans Sachs, is based on a historical figure, Hans Sachs (1494–1576), the most famous of the master-singers.

Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg occupies a unique place in Wagner’s oeuvre. It is the only comedy among his mature operas (he had come to reject his early Das Liebesverbot) and is also unusual among his works in being set in a historically well-defined time and place rather than in a mythical or legendary setting. It is the only mature Wagner opera based on an entirely original story, devised by Wagner himself, and in which no supernatural or magical powers or events are in evidence. It incorporates many of the operatic conventions that Wagner had railed against in his essays on the theory of opera: rhymed verse, arias, choruses, a quintet, and even a ballet.

From its entry on Wikipedia,

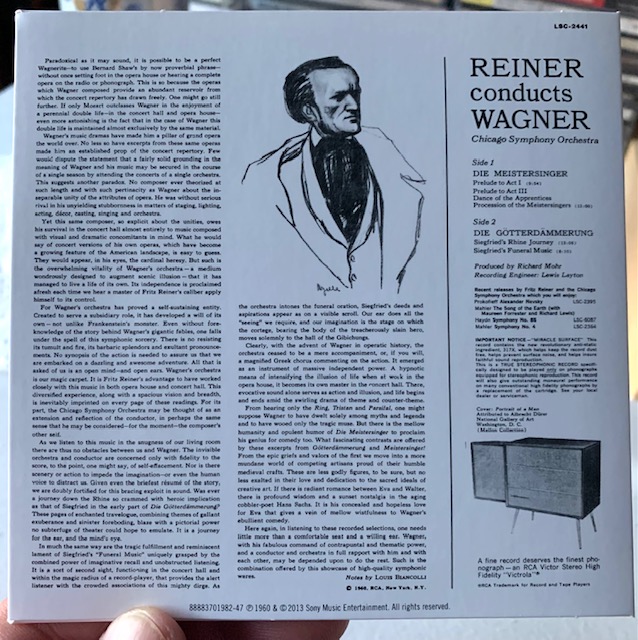

Götterdämmerung (Twilight of the Gods), WWV 86D, is the last in Richard Wagner’s cycle of four music dramas titled Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung, or The Ring for short). It received its premiere at the Bayreuth Festspielhaus on 17 August 1876, as part of the first complete performance of the Ring.

The title is a translation into German of the Old Norse phrase Ragnarök, which in Norse mythology refers to a prophesied war among various beings and gods that ultimately results in the burning, immersion in water, and renewal of the world. However, as with the rest of the Ring, Wagner’s account diverges significantly from his Old Norse sources.

It’s interesting that even information about Wagner is diffuse. It took me awhile to discovered when these two pieces of music were composed. I’m still not sure I know because I kept getting different answers.

From what I’ve been able to tell, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (“The Master-Singers of Nuremberg”) was composed in 1862. If that’s true, Wagner would have been 49.

Also, from what I’ve been able to tell, Götterdämmerung (Twilight of the Gods) was composed in 1848, which would mean Wagner was 35.

Both of these pieces of music were recorded on the same day – April 18, 1959 – at Orchestra Hall, Chicago. Maestro Reiner was in his 71st year of life.

The Subjective Stuff

Recording quality: 3.5 (sounds fuzzy and all mid-rangy to my ears)

Overall musicianship: 4

CD booklet notes: 2

CD “album cover” information: 4 (there’s a lot there!)

How does this make me feel: 3

Okay. Here’s the deal.

I could pretend to enjoy this music.

Or I could be honest and write, “It leaves me cold.”

Which would you prefer?

I know what I’d prefer – to pretend to enjoy this music. Honestly. I don’t like disliking something I paid so much to own.

If I had to choose a “favorite” between these two compositions, I’d have to admit Götterdämmerung (Twilight of the Gods) was more intriguing to me. Greater expanses of melody and less bombast, perhaps.

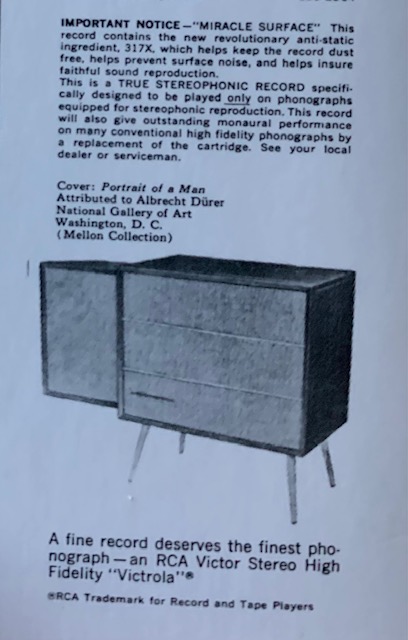

But what does it say about me if what I found the most interesting about this album was the ad on the back cover?

Recording quality: 5

Overall musicianship: 5

CD booklet notes: 2

CD “album cover” information: 4 (love the cartoon drawings)

How does this make me feel: 3.5