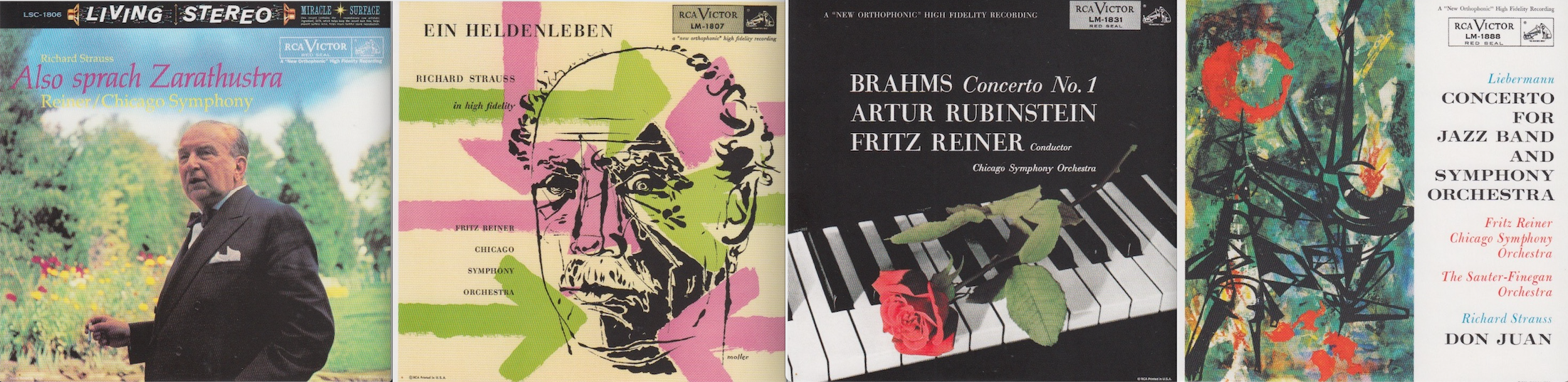

Tonight’s album is Unfinished Symphony and Symphony No. 5 in B-Flat by Franz Schubert (1787-1828).

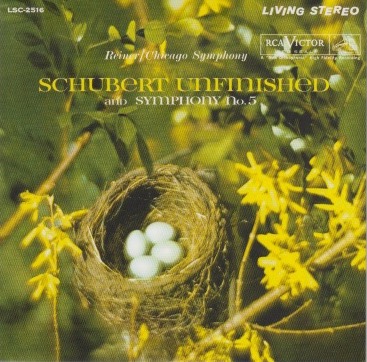

So, I figured that this august recording deserved a tasty accompaniment: an ice-cold Schlitz, for example, one of the few remaining beers from the good old days when men were men and beer was beer.

Schlitz – like Stroh’s, Carling Black Label, Hamm’s, and the unfortunately-now-it’s-a-Hipster-favorite beer Pabst Blue Ribbon (aka PBR) – was one of the greats.

You gotta keep in mind, when I write “greats,” I don’t mean it was an award-winning perfume beer, the kind of modern-day, micro-brew swill sporting an improbable name like Lavender Lush or Dragon’s Nuts that’s here one day and gone the next.

No. I’m talking about a stalwart beer, a beer-tasting beer that’s honest, made the way beer used to be made, before micro brews turned the adult beverage into something more akin to rose-petal wine than the ale Vikings would toss back before pillaging a village.

There’s nothing fancy about Schlitz. But it has a robust, genuine flavor that fits with any food. Or music.

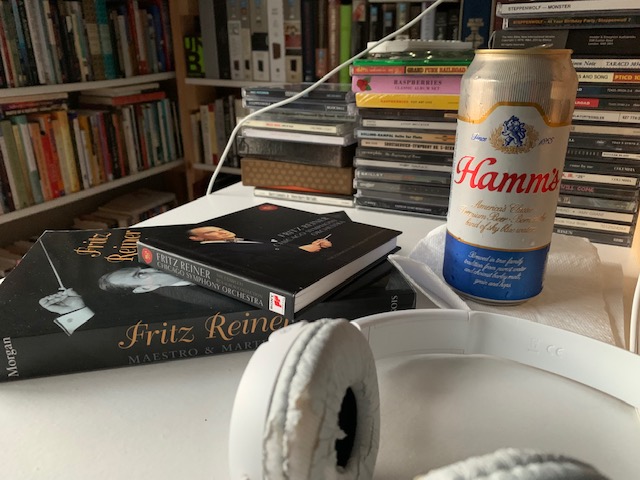

This is what I do.

If I’m in a Rat Pack mood, and I’m jonesing for a suitable beverage to go with the early 1960s era, I may search out a Schlitz, or a Jack Daniels – which was, supposedly, the Chairman of the Board’s beverage of choice.

If I’m hankering to relive my youth listening to The Who’s Quadrophrenia or Led Zeppelin’s Physical Graffiti, I’ll seek out a Stroh’s or a Carling Black Label (my beer of choice back then was the now-defunct Olympia beer, so I have to make do with the next best things).

If I’m in a Heminway mood, and I want to capture the feel of being an ex-pat in Paris in the 20s, I’ll buy some absinthe, a good cigar, crack open A Moveable Feast and read the master’s incomparable prose.

I love immersing myself in the trappings of the era in which I happen to be traipsing.

When I was a kid back in the 1970s, I used to do this with the Lord of the Rings books. I’d buy crumpet rings, make crumpets, slather them with butter and honey, and eat them while reading Lord of the Rings and sipping Twinings English Breakfast tea. I figured that was the most Hobbit-like thing I could do whilst reading about Hobbits.

Fast forward four decades. Here I am tonight with a man’s beer. (I wonder what Hobbits would think of Schlitz?)

Granted, Schlitz didn’t exist when Franz Schubert was a lad – although he missed it by that much, as Agent 86 used to say. Schubert died in 1828. Schlitz was first brewed in the U.S. in 1849. But I’m not trying to pair Schubert’s music with a suitable adult beverage. I’m pairing it with the year in which this recording was made – 1960.

What was a popular beer in America in 1960?

Schlitz. Of course.

And Carling Black Label, a beer that I discovered is also quite rare these days – even more rare than Schlitz, in fact. And that’s saying something.

I love rare things, hard-to-find things, unique things.

This is why I buy rare, usually limited-edition, box sets of music and listen to them, blogging daily about my sonic adventures. Not many people do that. Kinda makes me rare, too.

So, here I am listening to Schubert’s Symphony No. 5 in B-Flat while sipping a Hamm’s. (I switched to another old-timey beer tonight, just to get the full effect of a cultural shift.)

The Objective Stuff

From his entry on Wikipedia,

Franz Peter Schubert (1797-1828) was an Austrian composer of the late Classical and early Romantic eras. Despite his short lifetime, Schubert left behind a vast oeuvre, including more than 600 secular vocal works (mainly lieder), seven complete symphonies, sacred music, operas, incidental music, and a large body of piano and chamber music. His major works include “Erlkönig” (D. 328), the Piano Quintet in A major, D. 667 (Trout Quintet), the Symphony No. 8 in B minor, D. 759 (Unfinished Symphony), the ”Great” Symphony No. 9 in C major, D. 944, the String Quintet (D. 956), the three last piano sonatas (D. 958–960), the opera Fierrabras (D. 796), the incidental music to the play Rosamunde (D. 797), and the song cycles Die schöne Müllerin (D. 795) and Winterreise (D. 911).

Born in the Himmelpfortgrund suburb of Vienna, Schubert showed uncommon gifts for music from an early age. His father gave him his first violin lessons and his elder brother gave him piano lessons, but Schubert soon exceeded their abilities. In 1808, at the age of eleven, he became a pupil at the Stadtkonvikt school, where he became acquainted with the orchestral music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. He left the Stadtkonvikt at the end of 1813, and returned home to live with his father, where he began studying to become a schoolteacher. Despite this, he continued his studies in composition with Antonio Salieri and still composed prolifically. In 1821, Schubert was admitted to the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde as a performing member, which helped establish his name among the Viennese citizenry. He gave a concert of his own works to critical acclaim in March 1828, the only time he did so in his career. He died eight months later at the age of 31, the cause officially attributed to typhoid fever, but believed by some historians to be syphilis.

Appreciation of Schubert’s music while he was alive was limited to a relatively small circle of admirers in Vienna, but interest in his work increased greatly in the decades following his death. Felix Mendelssohn, Robert Schumann, Franz Liszt, Johannes Brahms and other 19th-century composers discovered and championed his works. Today, Schubert is ranked among the greatest composers of Western classical music and his music continues to be popular.

Jeepers creepers, man. Here’s another Classical composer who died way too young. I mean, come on. Thirty one?

From its entry on Wikipedia,

Franz Schubert’s Symphony No. 8 in B minor, D 759 (sometimes renumbered as Symphony No. 7, in accordance with the revised Deutsch catalogue and the Neue Schubert-Ausgabe, commonly known as the Unfinished Symphony (German: Unvollendete), is a musical composition that Schubert started in 1822 but left with only two movements—though he lived for another six years. A scherzo, nearly completed in piano score but with only two pages orchestrated, also survives.

It has been theorized by some musicologists, including Brian Newbould, that Schubert may have sketched a finale that instead became the big B minor entr’acte from his incidental music to Rosamunde, but all evidence for this is circumstantial. One possible reason for Schubert’s leaving the symphony incomplete is the predominance of the same meter (triple meter). The first movement is in 3/4, the second in 3/8 and the third (an incomplete scherzo) again in 3/4. Three consecutive movements in basically the same meter rarely occur in symphonies, sonatas, or chamber works of the most important Viennese composers.

Schubert’s Eighth Symphony is sometimes called the first Romantic symphony due to its emphasis on the lyrical impulse within the dramatic structure of Classical sonata form. Furthermore, its orchestration is not solely tailored for functionality, but specific combinations of instrumental timbre that are prophetic of the later Romantic movement, with astonishing vertical spacing occurring for example at the beginning of the development.

To this day, musicologists still disagree as to why Schubert failed to complete the symphony. Some have speculated that he stopped work in the middle of the scherzo in the fall of 1822 because he associated it with his initial outbreak of syphilis—or that he was distracted by the inspiration for his Wanderer Fantasy for solo piano, which occupied his time and energy immediately afterward. It could have been a combination of both factors.

From its entry on Wikipedia,

Franz Schubert’s Symphony No. 5 in B♭ major, D. 485, was written mainly in September 1816 and completed on October 3, 1816. It was finished six months after the completion of his previous symphony.

In character, the writing is often said to resemble Mozart; Schubert was infatuated with the composer at the time he composed it, writing in his diary on June 13 of the year of composition, “O Mozart! Immortal Mozart! what countless impressions of a brighter, better life hast thou stamped upon our souls!” This is reflected particularly in the lighter instrumentation, as noted above. Indeed, the instrumentation matches that of the first version (without clarinets) of Mozart’s 40th symphony. For another example, there is a strong similarity between the opening themes of the second movement of D. 485 and the last movement of Mozart’s Violin Sonata in F major, K. 377.

Unfinished Symphony was recorded on March 26, 1960. Symphony No. 5 was recorded on April 27, 1960. Both were recorded in Orchestra Hall. Maestro Reiner was in the 72nd year of life.

The Subjective Stuff

Recording quality: 4 (Unfinished) / 5 (Symphony No. 5)

Overall musicianship: 5

CD booklet notes: 2

CD “album cover” information: 4 (not much more needs to be written than what’s already here)

How does this make me feel: 5 (for both compositions)

I really like this music.

I mean, a lot.

I realize it could be the Schlitz and Hamm’s talking. But I don’t think so.

I think I was genuinely captivated by Schubert’s creativity.

I found the Unfinished Symphony haunting, almost ominous in how it began. But then it quickly moved through several moods, from lyrical to beautiful to lively and back to ominous. Toss in a little pizzicato action (which always sounds like one cartoon character sneaking up on another one), and I’m sold.

The first movement (“Allegro moderato”) was gorgeous.

The second, which also utilized pizzicato, was less compelling to me. But it still painted a broad mental canvas in my mind.

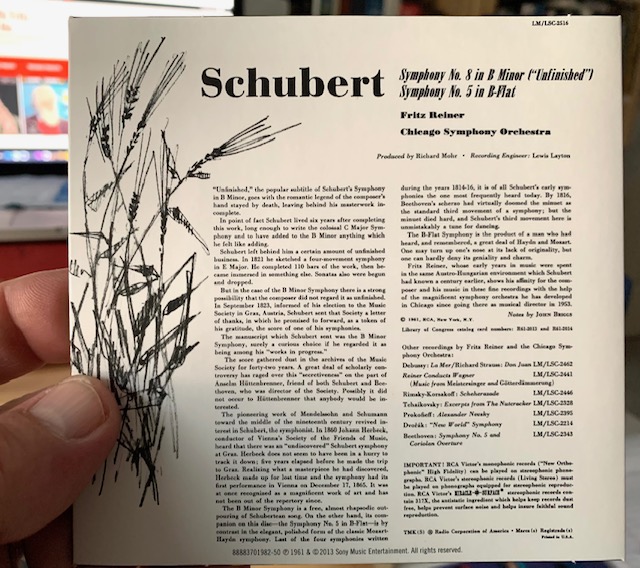

The liner notes – written by John Briggs (1916-1990) – on the back of the album offered this curious insight:

Schubert left behind him a certain amount of unfinished business. In 1821 he sketched a four-movement symphony in E Major. He completed 110 bars of the work, then became immersed in something else. Sonatas also were begun and dropped.

But in the case of the B Minor Symphony there is a strong possibility that the composer did not regard it as unfinished. in September 1823, informed of his election to the Music Socidety in Graz, Austria, Schubert sent that Society a letter of thanks, in which he promised to forward, as a token of his gratitude, the score of one of his symphonies.

The manuscript which Schubert sent was the B Minor Symphony, surely a curious choice if he regarded it as being among his “works in progress.”

I’ve read a lot of music-critic essays. But this one, by Briggs, is one of the best. Well written. Clear. And revealing. I encourage you to buy the album and read the rest of it for yourself.

The second composition on this album (Symphony No. 5) is so much fun! It’s lively, compelling, and robust.

This may be the first time I’ve ever heard a piece by Schubert – at least, not one recorded by one of the world’s finest orchestras and conductors. But I think I’d remember Schubert’s style had I heard it before.

I like his work! He’s firmly lodged in the Classical era, which is my favorite. But he sent out little tendrils into the Romantic era as well.

I’m going to have to seek out more of his compositions.

I’d definitely listen to this CD again!