Ahhh, now this is more like it.

Pure, unadulterated Beethoven.

I realize life requires variety, even experiencing/tasting/seeing/hearing things we don’t particularly like, just so that we’ll appreciate the things we do like.

And I totally get that if all I listened to was Beethoven, I’d eventually get sick of Ludwig’s creative endeavors.

As much as I like the Beatles or Led Zeppelin or Deep Purple or Rush, if all I listened to was any of those bands, 24/7, I’d eventually not want to hear another note from them.

I get it.

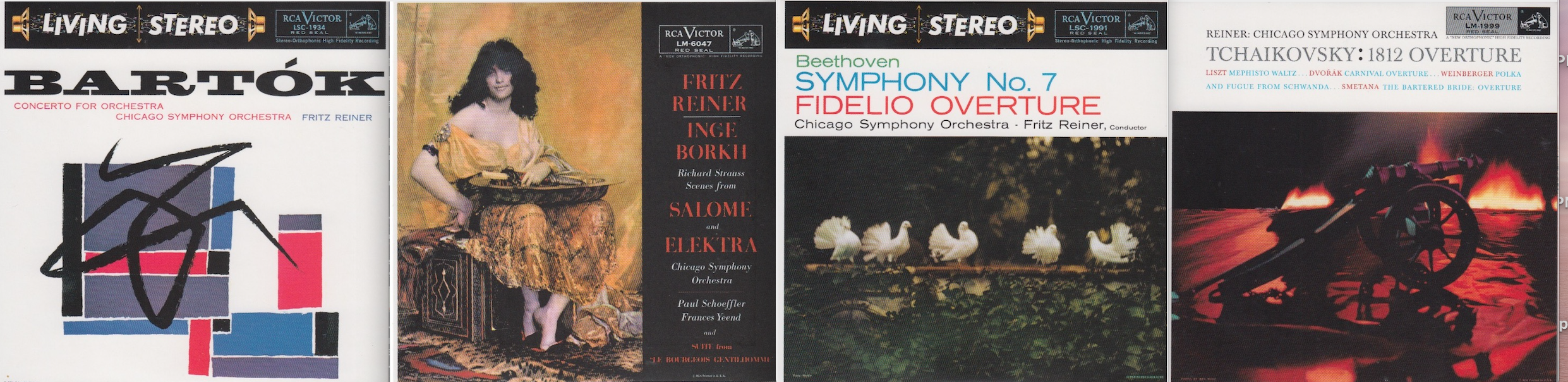

But whenever I listen to a lot of Bartok, Strauss, Tchaikovsky, or Brahms, and the rotation returns to Beethoven, my molecules line up in a nice happy configuration. (That’s a reference, by the way, to Dr Masaru Emoto, the Japanese researcher who photographed water crystals under various kinds of stimuli – including raucous music – and observed how their shape differed depending on the type of stimuli. His conclusion was that if water, up with which the human body is mostly made, is “distressed” or “happy” based on external factors, what does that mean for human beings?)

So my molecules are lined up nicely this morning.

The Objective Stuff

If you’d like to read more about Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827), visit his entry on Wikipedia.

From its entry on Wikipedia,

Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony No. 1 in C major, Op. 21, was dedicated to Baron Gottfried van Swieten, an early patron of the composer. The piece was published in 1801 by Hoffmeister & Kühnel of Leipzig. It is not known exactly when Beethoven finished writing this work, but sketches of the finale were found to be from 1795.

The symphony is clearly indebted to Beethoven’s predecessors, particularly his teacher Joseph Haydn as well as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, but nonetheless has characteristics that mark it uniquely as Beethoven’s work, notably the frequent use of sforzandi, as well as sudden shifts in tonal centers that were uncommon for traditional symphonic form (particularly in the 3rd movement), and the prominent, more independent use of wind instruments. Sketches for the finale are found among the exercises Beethoven wrote while studying counterpoint under Johann Georg Albrechtsberger in the spring of 1797.

The above description of the Symphony included a word with which I was not familiar: sforzandi.

So I looked it up on Wikipedia:

Sforzando (or sforzato, forzando, forzato) indicates a forceful accent and is abbreviated as sf, sfz or fz. There is often confusion surrounding these markings and whether or not there is any difference in the degree of accent. However, all of these indicate the same expression, depending on the dynamic level, and the extent of the sforzando is determined purely by the performer.

Beethoven was between the ages of 25 and 30 when he composed his first symphony. It was recorded on May 8, 1961, at Orchestra Hall, Chicago. Maestro Reiner was in his 73rd year of life.

The Subjective Stuff

Recording quality: 4 (seems a little fuzzy to me)

Overall musicianship: 4

CD booklet notes: 2

CD “album cover” information: 0 (total misuse of space)

How does this make me feel: 4

For my rant about this album and its non-existent credits and lack of original booklet, please see yesterday’s post (Day 54).

Although Beethoven’s First Symphony isn’t my favorite of his nine, it’s still Beethoven, and he’s still a genius.

As I mentioned yesterday, when I undertook my last Beethoven project (162 Days With Beethoven And Me), which I described this way: “Eighteen CD box sets. Seventeen conductors. One-hundred sixty-two days. Five and a half months.”

So I became very familiar with Beethoven’s music, and of which conductors and/or orchestras were the “best,” according to my aural palette. Not once did I encounter Fritz Reiner, probably because I only chose Beethoven cycles that were complete in box sets, easily obtained, and not costing a small fortune. So I have no apples-to-apples comparison between Reiner and one of the 17 other conductors to which I listened during that project.

The Reiner performances seem to lack power. They’re phenomenally well played and conducted. Don’t get me wrong. But they don’t have, say, Leonard Bernstein’s exuberance and verve. These RCA Victor performances are solid, trustworthy, and, at times, noteworthy. But not many of them electrify me.

Wikipedia’s description of this symphony is accurate. It does remind me of Haydn and Mozart in a few places. But it’s more dynamic than Haydn. And more powerful than Mozart.

I’d probably listen to this album again, but only if I couldn’t find a few of the 18 box sets from my previous Beethoven project.