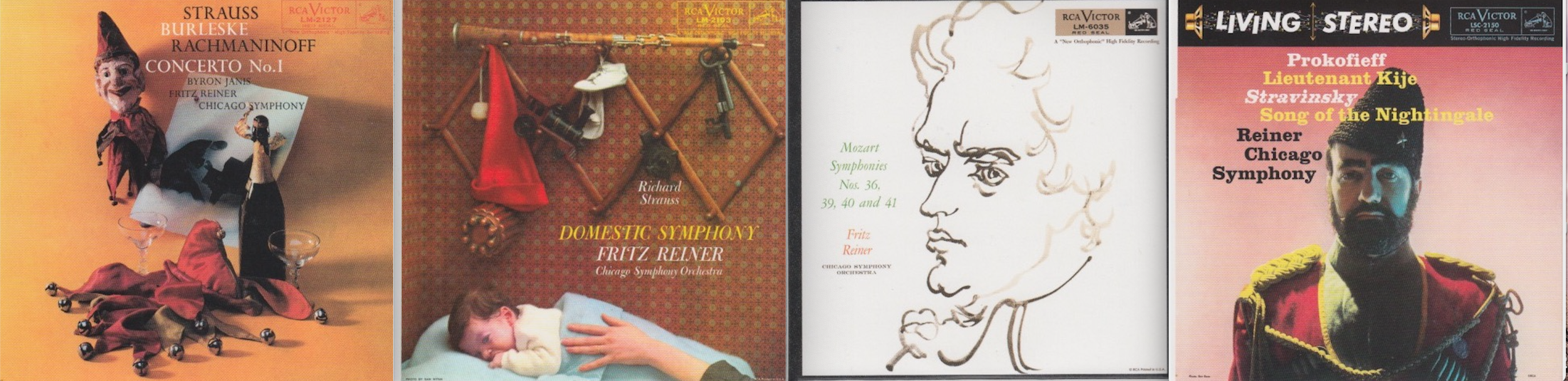

This album holds the distinction of being “Fritz Reiner’s last recording with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.”

According to the web site Stokowski (which includes what purports to be a complete list of Fritz Reiner and CSO concerts here), informs us that Fritz Reiner’s last performance with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra occured on April 20, 1963 (which I looked up and was a Saturday) and this was what they played:

Rossini: “Semiramide” Overture

Brahms: Symphony no 2

INTERMISSION

Beethoven: Piano Concerto no 4 (Van Cliburn)

Fritz Reiner’s final concert with the Chicago Symphony

So, what it appears happened is Fritz Reiner and the CSO performed Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 4 with Van Cliburn on Saturday, April 20, and then recorded it on Monday, the 22nd, and Tuesday, the 23rd. And that was the last time Fritz Reiner performed or recorded with the CSO. The great maestro died on November 15, 1963 at the age of 74, a month shy of his 75th birthday.

By the way, Stokowski is, of course, the legendary conductor Leopold Stokowski (1882-1977) who was born six years before Fritz Reiner, and lived 14 years longer than Fritz Reiner.

From his entry on Wikipedia,

Leopold Anthony Stokowski (18 April 1882 – 13 September 1977) was a British conductor of mixed Polish and Irish descent. One of the leading conductors of the early and mid-20th century, he is best known for his long association with the Philadelphia Orchestra and his appearance in the Disney film Fantasia with that orchestra. He was especially noted for his free-hand conducting style that spurned the traditional baton and for obtaining a characteristically sumptuous sound from the orchestras he directed.

Stokowski was music director of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, the Philadelphia Orchestra, the NBC Symphony Orchestra, New York Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra, the Houston Symphony Orchestra, the Symphony of the Air and many others. He was also the founder of the All-American Youth Orchestra, the New York City Symphony, the Hollywood Bowl Symphony Orchestra and the American Symphony Orchestra.

Stokowski conducted the music for and appeared in several Hollywood films, most notably Disney’s Fantasia, and was a lifelong champion of contemporary composers, giving many premieres of new music during his 60-year conducting career. Stokowski, who made his official conducting debut in 1909, appeared in public for the last time in 1975 but continued making recordings until June 1977, a few months before his death at the age of 95.

Other than being a famous conductor, Stokowski has no bearing on today’s performance from Maestro Reiner and pianist Van Cliburn. I just thought I’d throw that in as a bonus. Free of charge.

Today’s composition is from the incomparable Ludwig van Beethoven, my favorite composer. From its entry on Wikipedia,

Ludwig van Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 4 in G major, Op. 58, was composed in 1805–1806. Beethoven was the soloist in the public premiere as part of the concert on 22 December 1808 at Vienna’s Theater an der Wien.

It was premiered in March 1807 at a private concert of the home of Prince Franz Joseph von Lobkowitz. The Coriolan Overture and the Fourth Symphony were premiered in that same concert. However, the public premiere was not until a concert on 22 December 1808 at Vienna’s Theater an der Wien. Beethoven again took the stage as soloist. The marathon concert saw Beethoven’s last appearance as a soloist with orchestra, as well as the premieres of the Choral Fantasy and the Fifth and Sixth symphonies. Beethoven dedicated the concerto to his friend, student, and patron, the Archduke Rudolph.

A review in the May 1809 edition of the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung states that “[this concerto] is the most admirable, singular, artistic and complex Beethoven concerto ever”. However, after its first performance, the piece was neglected until 1836, when it was revived by Felix Mendelssohn. Today, the work is widely performed and recorded, and is considered to be one of the central works of the piano concerto literature.

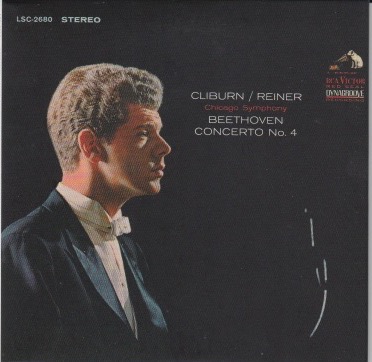

Beethoven was between 35 and 36 years of age when he composed this. It was recorded on April 22 and 23, 1963. This album is the first I’ve noticed with the word “Dynagroove” on the cover. It doesn’t read “Living Stereo” any more. Just “Stereo.” And now it reads “DYNAGROOVE” (in all caps) on the cover. The hell is “DYNAGROOVE”?

From its entry on Wikipedia,

Dynagroove is a recording process introduced in 1963 by RCA Victor that, for the first time, used analog computers to modify the audio signal used to produce master discs for LPs. The intent was to boost bass on quiet passages, and reduce the high-frequency tracing burdens (distortion) for the less-compliant, “ball” or spherical-tipped playback cartridges then in use. With boosted bass, tracing demands could be reduced in part by reduced recording levels, sometimes supplemented by peak compression. This added top-end margin permitted selective pre-emphasis of some passages for greater perceived (psychological) brilliance of the recording as a whole. As with any compander, the program material itself changed the response of the Dynagroove electronics that processed it. But, because the changes were multiple (bass, treble, dynamic range) and algorithmic (thresholds, gain curves), RCA justifiably referred to the analog device as a computer.

RCA claimed that Dynagroove had the effect of adding brilliance and clarity, realistic presence, full-bodied tone and virtually eliminated surface noise and inner groove distortion. In addition, Dynagroove recordings were mastered on RCA magnetic tape. Hans H. Fantel (who wrote liner notes on the first Dynagroove releases) summed it up with, “[Dynagroove] adds up to what is, in my opinion, a remarkable degree of musical realism. The technique is ingenious and sophisticated, but its validation is simple: the ear confirms it!”

The process was not received well by some industry commentators, with many audio engineers of the time referring to Dynagroove as “Grindagroove”. Dynagroove was also sharply criticized by Goddard Lieberson of the competing label Columbia Records, who called it “a step away from the faithful reproduction of the artist’s performance;” and by Harry Pearson, founder of The Absolute Sound, who termed it “Dynagroove, for that wooden sound.” Another noted detractor of Dynagroove was J. Gordon Holt, the founder of Stereophile magazine, who in December 1964 wrote a highly unfavourable article entitled “Down with Dynagroove!” Holt, a noted audio engineer and writer of the 1960s and 1970s, slammed Dynagroove as introducing “pre-distortion” into the mastering process, making the records sound worse if they were played on high-quality phono systems.

The Subjective Stuff

Recording quality: 4.5

Overall musicianship: 5

CD booklet notes: 2

CD “album cover” information: 2

How does this make me feel: 4.5

I don’t know from DYNAGROOVE (and what that even means for a Compact Disc release), but this is a well-balanced, lush-yet-clear recording that doesn’t feature a piano recorded hot enough to give me a headache, yet with enough bedding of orchestra that it all fits together like a hand in a glove.

This is a compelling piece of music, anyway. Somewhat melancholy, too. But it’s even more so knowing this was the last recording made by Maestro Reiner and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

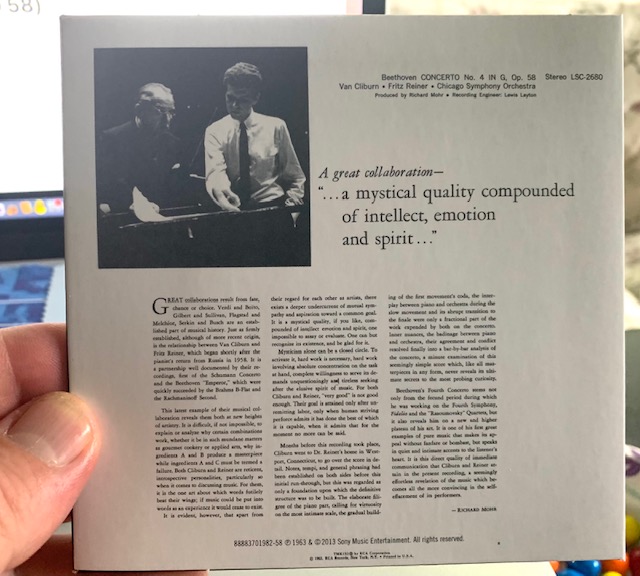

The essay on the back cover is by Richard Mohr. It’s important to note that because the essay describes the partnership, the meeting of the minds as it were, of Van Cliburn and Maestro Reiner.

In his Wikipedia entry, it is written of the late Mr. Mohr (1919-2002),

Martin Bernheimer, former music critic of the Los Angeles Times said of him that “He had a great eye and ear for talent and for putting important people together for projects that had lasting value to the music lover. He was an enabler with great imagination and great taste. My impression was he got (the artists) to behave like pussy-cats.” His body of work earned him five Grammy Awards for Best Opera Recording of the year and at least twenty-five Grammy nominations. He is also widely known for his appearances on the Met Opera Quiz broadcasts as a panelist and later as producer of the Metropolitan Opera radio broadcast intermission features.

And that’s precisely what the essay is about: the mystical conneciton between Van Cliburn and Fritz Reiner.

To be honest, I’m not sure I hear anything mystical or even special going on. I hear the same level of musical aptitude with Van Cliburn as I did with Arthur Rubinstein and Byron Janis.

By the way, the fourth movement of this zippy little concert is a hoot and a half. Rollicking piano playing and boisterous orchestration. Lotta fun.

I’d listen to this album again!