Okay. I’ll admit it.

When I saw that today’s composer was Tchaikovsky, I cringed. Just a little.

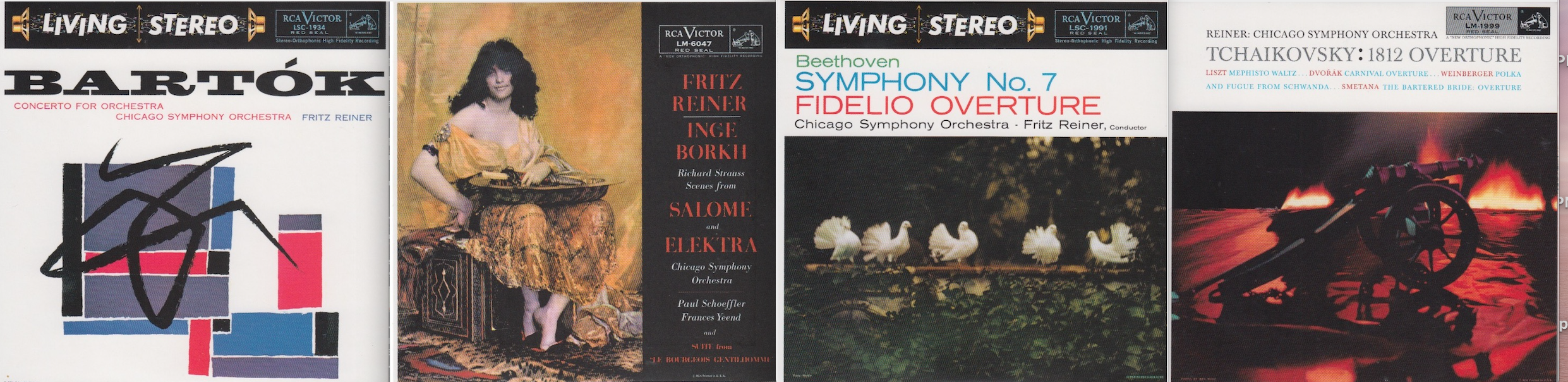

I’ve encountered Pyotr twice before in my Fritz Reiner project:

Day 7, with his Piano Concerto No. 1, and

Day 13, with his 1812 Overture

In my first encounter, I compared Tchaikovsky to Swedish heavy metal guitarist Yngwie Malmsteen because of his propensity to play endless flurries of notes. Don’t get me wrong, there’s nothing wrong with playing a flurry of notes. However, such musicianship gets wearisome very quickly. And, to my ears, it detracts from the overall composition.

It’s like one musician in an orchestra is constantly soloing.

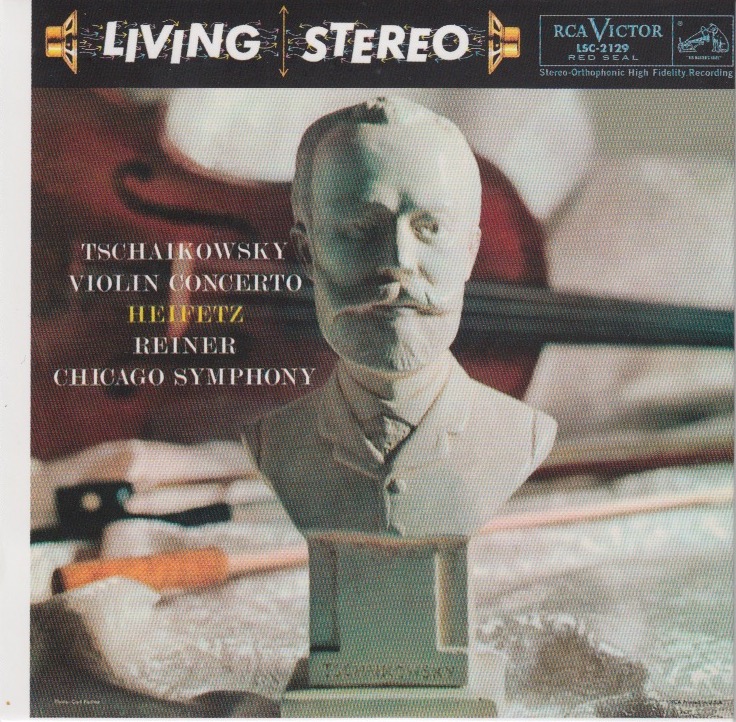

In this case, the soloist is famed violinist Jascha Heifetz, one of the greatest musicians who ever lived. Like pianist Arthur Rubinstein, when Heifetz appears on the scene, suddenly I’m all ears. I am compelled to take notice. His presence in a recording elevates it to legendary status. Immediately.

Yet, even Heifetz can get tiresome if the majority of time the baton points to him he’s playing so many notes that the score must be black with them. Rule of thumb: an occasional flurry showcases talent, while frequently flurries showboat it. There’s a difference.

From its entry on Wikipedia,

The Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 35 was the only concerto for violin composed by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky in 1878 and is one of the best-known violin concertos.

The piece was written in Clarens, a Swiss resort on the shores of Lake Geneva, where Tchaikovsky had gone to recover from the depression brought on by his disastrous marriage to Antonina Miliukova. He was working on his Piano Sonata in G major but finding it heavy going. Presently he was joined there by his composition pupil, the violinist Iosif Kotek, who had been in Berlin for violin studies with Joseph Joachim. The two played works for violin and piano together, including a violin-and-piano arrangement of Édouard Lalo’s Symphonie espagnole, which they may have played through the day after Kotek’s arrival. This work may have been the catalyst for the composition of the concerto.v Tchaikovsky wrote to his patroness Nadezhda von Meck, “It [the Symphonie espagnole] has a lot of freshness, lightness, of piquant rhythms, of beautiful and excellently harmonized melodies…. He [Lalo], in the same way as Léo Delibes and Bizet, does not strive after profundity, but he carefully avoids routine, seeks out new forms, and thinks more about musical beauty than about observing established traditions, as do the Germans.” Tchaikovsky authority Dr. David Brown writes that Tchaikovsky “might almost have been writing the prescription for the violin concerto he himself was about to compose.”

SIDEBAR: As is often the case when I go to the movies or to a restaurant, the place could be empty. But as soon as I sit down and make myself comfortable, a couple of clowns will appear out of nowhere and select the seats and/or table closes to me – and then behave as if they’re in a sports bar, tanked up on a few Budweisers, cheering for the Red Sox to beat the Yankees.

Such is the case this morning. The place was literally just me and one or two other people. I was off in a lonely corner. Suddenly, I heard loud conversation and I turned about to see the table immediately behind me – literally within arm’s reach – occupied by a couple of clowns in full-on loud-talk mode.

To drown them out, I cranked the Tchaikovsky to just below the pain threshold.

And I did what I enjoy doing most in these projects: discovered new things.

In this case, I discovered Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto was featured in a 1947 movie called Carnegie Hall that also features – get this – Fritz Reiner, Jascha Heifetz, Arthur Rubinstein, Lily Pons, and a host of other Classical musicians who belong on Mt. Olympus.

How am I just now learning about this movie?

Believe me, I wasted no time ordering it from Amazon.

By the way, I’d often heard the name Lily Pons (for example, in a Woody Allen routine), but I never really knew who she was. I figured she was an opera singer, sure. But I didn’t know she was considered one of the greatest Coloratura sopranos of all time. I may have known this before, but I don’t recall knowing what Coloratura meant. Now, I do. And now I have a word to describe an operatic voice:

Coloratura is an elaborate melody with runs, trills, wide leaps, or similar virtuoso-like material, or a passage of such music. Operatic roles in which such music plays a prominent part, and singers of these roles, are also called coloratura. Its instrumental equivalent is ornamentation.

The Objective Stuff

This was recorded at Orchestra Hall in Chicago, on April 19, 1957. The piece was composed in the year 1878 when Tchaikovsky was 38. It was directed by Fritze Reiner was he was 69. Heifetz was 56 when he performed in this recording. It was release in the Living Stereo series by RCA Victor.

The Subjective Stuff

Recording quality: 5

Overall musicianship: 5

CD booklet notes: 2.5

CD “album cover” information: 3.5

How does this make me feel: 5

I was all prepared to detest this recording when it tip-toed up behind me (pizzicato-style) and kicked my keister.

This concerto was written in three movements:

- Allegreto Moderato

- Canzonetta: Andante

- Allegro Vivacissimo

The first movement comes perilously close to that flurry-of-notes showboat style of playing that usually leaves me cold. Even still, it’s Heifetz. And I can appreciate his mastery even if I think he’s playing way too many notes.

Movement II is what caused me to sit up and take notice. The slower, more emotive Andante was a much-needed reprieve from the flurry of Movement I. I loved this.

However, and this may amaze you (whomever “you” is), it was the last few minutes of Movement III that cemented the deal. Even though the third movement (Allegro Vivacissimo) is a return to the note flurry, from about 6:30 onward I was hooked. This was constructed like some of my favorite Mozart and Beethoven pieces. Big, bold, percussive sound. This passage sounded more like Classical-era music than Romantic-era music.

In spite of myself, I loved this performance and would listen to it again.